You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Corequisite math and English courses are gaining momentum as colleges look for new ways to replace remedial education.

g-stockstudio/iStock/Getty Images

At a Board of Regents meeting Wednesday, Tristan Denley, Louisiana’s deputy commissioner of academic affairs and innovation, shared an encouraging statistic: Course completion for entry-level math has increased nearly fivefold over the past year at the state’s public higher education institutions.

He credited a new corequisite course structure, introduced last fall, that takes students who previously would have been slotted into a non-credit-bearing remedial course and places them directly into credit-bearing, entry-level math. At the same time, they take a partner course—known as a corequisite—in which they receive more individualized assistance to fill any gaps left from their high school education. It’s a concept that has slowly gained momentum in states including Georgia, Illinois, Oregon and Tennessee; the results from Louisiana’s first full year of implementation may help explain why.

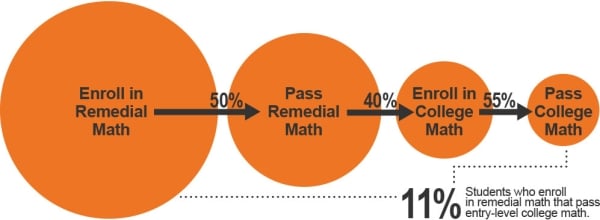

According to Denley, 52 percent of students taking corequisite math courses in 2023–24 passed a credit-bearing math class during their first year. That’s up from what he called a “dismal” 11 percent “pass-through” rate for students who started in remedial math and eventually completed the entry-level course in 2020–21.

“The traditional stand-alone remediation is set up from a deficit point of view,” Denley said. “The vast majority of those students never went on to take the credit-bearing class at all, let alone fail or pass it.”

By contrast, he said, “corequisite courses have an asset approach. It really is an example of the system saying, ‘We believe you can pass this, and we’re willing to work with you to make sure that that happens.’”

Implementing corequisites often requires a systemwide overhaul that includes curriculum training, revamped advising programs and more, but access and equity advocates say it’s an investment worth making. Eliminating remedial courses and replacing them with corequisite support, they argue, will boost not only course completion but also degree attainment rates, particularly for first-time, low-income students from historically underserved communities and returning adult learners who are key to workforce development.

“It’s a way of meeting students where they’re at and making sure that we’re not putting it on the students to change. But how are we changing our systems—in this case, our curriculum, our pedagogy—to do what’s going to be best for students?” said Brandon Protas, assistant vice president at Complete College America, a national advocacy group that has been a leading voice in the promotion of corequisite courses. “It’s the first step towards that larger goal.”

Success Across the Board

The overwhelmingly positive results Denley shared with the board are the culmination of years of work.

Pilot corequisite programs were established at individual institutions in Louisiana as early as 2020, but it wasn’t until Denley—who previously led corequisite campaigns in both Tennessee and Georgia—moved to the Bayou State in 2022 that the course-placement policies changed at a system level.

The statewide math corequisites saw success across the board. Although students who entered college having scored 16 to 18 on the ACT saw more significant improvement rates (about a 40-percentage-point increase) than their peers with a score of 13 to 15 (between a 25- and 35-percentage-point increase).

The delivery of corequisite courses varied from college to college, Denley explained. Some institutions offered the corequisite as one six-credit block course with the same instructor, while others placed students in one general math class and a different, smaller tutoring section for the companion course. Regardless, students were enrolled in some form of added support during the same term as their gateway course.

In addition to saving students time and money, thereby increasing the likelihood they will stay enrolled, the simultaneous courses serve to reinforce the material they’re learning, Denley said, which plays a big part in helping them pass.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Data from the Louisiana Board of Regents

“You’re getting this pedagogical and instructional support as you are grappling with concepts that you haven’t understood in the past,” he said. “And it’s just a lot more effective when you are getting that support at the time, rather than six months earlier.”

Other research supports Louisiana’s findings. A March 2024 working paper published through the Annenberg Institute at Brown University, which analyzes Tennessee’s corequisite program, found that corequisite students, particularly those with lower placement scores, were still more likely to drop out and less likely to earn short-term certificates than students who tested into the regular entry-level courses and didn’t need any remedial or corequisite instruction.

Louisiana plans to scale corequisites statewide starting this fall, beginning by eliminating remedial courses in English programs. And Kim Hunter Reed, the state’s commissioner of higher education, aims to continue expanding from there.

“In order for Louisiana to reach its attainment goal of 60 percent of working-age adults holding a degree or credential by 2030, we must adopt what works and accelerate student success,” she said in a press release. “Our goal is to improve reform efforts further and expand them as well.”

Faculty Buy-In

Faculty members and higher education experts largely applaud the idea of universal corequisite courses, saying that they will be key to helping today’s students succeed.

Thomas Reynolds, head of the English department at Northwestern State University, is one of 13 faculty members in the state being trained as a “Mindset Meauxtivator” (named in honor of the state’s French-derived Cajun culture and language, in which people often use the suffix “-eaux” to make an “o” sound). That means that in addition to leading the introduction of corequisite classes at his institution, Reynolds will undergo training from the University of Virginia’s Motivate Lab and be an advocate for growth mindsets.

The concept of a growth mindset, which has gained popularity in both K-12 and higher education, centers on teaching in a way that encourages students to take on challenges and view failure not as a roadblock but as a springboard for growth.

Reynolds believes that some of this mindset is inherently built into corequisite programs in a way that can be hard to foster in a remedial course structure. “Remedial courses had a psychological effect on students. They knew they were taking a course that nobody else had to take … in that way, a lot of students felt less than,” he said. “Removing those layers [via corequisites] has made it more possible for these students to be successful, not to dumb down the curriculum, but to give them the time and instruction they need to actually learn.”

But some doubters remain. John Schlueter, an English instructor at Saint Paul Community and Technical College in Minnesota, worries the improvements in gateway course completion don’t necessarily translate to the downstream goal of higher degree-attainment rates. He argues that remediation is not the enemy. “Initially, when you’re shown the data for corequisite reforms, you’re sort of blown away,” he said. “But as you start to dig into the data, you realize that you’re not given the full picture.

“If we really want to increase graduation rates, we need to worry more about the kind of suite of supports that are around students throughout their college experience, and not just compressing curricula,” Schlueter said.

That argument, however, has received pushback from multiple voices, including Protas from Complete College America; other studies, including a January 2023 report from Trinity College in Connecticut and the City University of New York, show the opposite—that students earn degrees quicker and increase their earnings if they get extra help in credit-bearing courses rather than taking remedial courses.

Maggie Fay, a senior research associate of the Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College, acknowledged that “not everyone is always on board with the transition” to corequisites, but she said the stats from Louisiana “look like really positive, exciting results.” And yet, while they’re a great start, more still needs to be done to boost attainment.

“To me, the takeaway is that corequisites are necessary, but not sufficient for moving the needle on graduation rates,” she said. “Colleges need to complement reforms to developmental education with other reforms in terms of ensuring that students are getting support to make timely progress to complete their degree, that they’re getting advising support on course selection and that they’re clear on transfer requirements.”