You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As hurricanes, wildfires and other environmental disasters become more frequent and severe, college students are grappling with climate anxiety.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | gorodenkoff/iStock/Getty Images | David McNew/Getty Images | NOAA

When Liv Barefoot first heard Hurricane Helene was headed toward the University of North Carolina at Asheville, she didn’t expect it to upend her senior year and escalate her anxiety about climate change.

That’s because she’d always considered the North Carolina mountains as something of a “climate safe haven,” secure from the threat of the types of hurricanes that have long devastated Florida and Louisiana residents.

“We were expecting some flash flooding, per usual, when we have more severe storms,” said Barefoot, who is the student body president at UNC Asheville. “None of us were prepared—mentally or otherwise—for the amount of destruction and catastrophic flooding that was going to happen as a result of this.”

But once the Category 4 hurricane made landfall in Asheville on the evening of Sept. 27, the storm’s severity started to sink in.

“My fear was the trees cracking all around me. Hard rain was coming down in curtains, and I could see the trees that were still standing blowing pretty hard,” said Barefoot, who lost power and cellphone service early the next morning and was unable to communicate with her family for two days. “That’s when I realized this was pretty intense. I don’t think I’ve ever lived through a hurricane that’s been this bad before. I started to get more anxious about what this was going to look like.”

Hurricane Helene knocked down dozens of trees on and off the campus of UNC Asheville.

Liv Barefoot

Daylight exposed the extent of the damage (now estimated at around $50 billion) to UNC Asheville, the surrounding community and much of western North Carolina. As a result of the destruction, the university lost access to clean water and sent all its nearly 3,000 students home, including the 46 percent of them who live in on-campus housing.

Since that first morning, UNC Asheville officials have started to rebuild and, in the meantime, suspended in-person classes until the spring. Classes resumed online at the end of last month, and the residence halls have since reopened, though as of last week the campus still wasn’t fully supplied with drinkable water.

UNC Asheville and the other campuses affected by hurricanes, wildfires and other natural disasters this year will rebuild. They usually do. But experts say those resilience plans should also take into account that with every natural disaster like Helene, students become more anxious about their increasing likelihood of experiencing many more severe weather events in their lifetimes, no matter what part of the country they live in.

“It’s always been on my radar a little bit,” Barefoot said about the long-term effects of climate change. “I don’t know if it ever fully reached a level of consistent climate anxiety until this point.”

She’s far from alone. And that anxiety is something UNC Asheville and other colleges across the country have been trying for years to soothe and redirect into solutions.

Generational, Political Divides

According to a peer-reviewed study published in The Lancet Planetary Health last month, 85 percent of Americans ages 18 to 25 (across the political spectrum) worry about the impact of climate change on people and the planet. More than 60 percent said climate change makes them feel anxious, powerless, afraid, sad and angry, and 38 percent said their feelings about climate change affect their ability to function daily.

“As people report that the area where they live is affected by more types of climate-related severe weather events, their distress increases incrementally as well as their desire for action,“ said Eric Lewandowski, lead author of the study and a clinical associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Ninety-nine percent of scientists attribute global temperature increases over the past 30 to 40 years to human-generated greenhouse gases, which present “significant risks to humankind” if they continue, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Climate Portal.

Yet the general public is far more divided by age and political party affiliation.

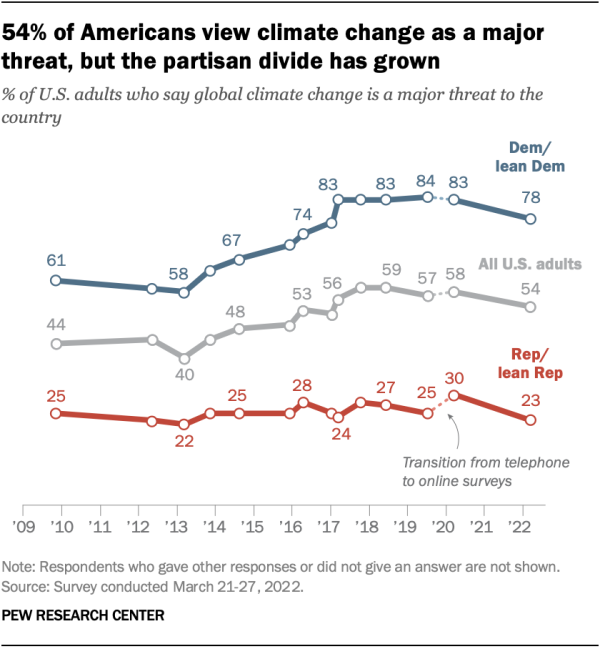

While there’s scientific consensus about the threat of climate change, the general public is far more divided.

Pew Research Center

Although 54 percent of all Americans view climate change as a major threat, that’s true for 78 percent of Democrats and just 23 percent of Republicans, according to a 2023 study from the Pew Research Center. But even within conservative circles, the generational divide is stark: 67 percent of Republicans under the age of 30 prioritize the development of alternative energy sources, whereas 75 percent of Republicans 65 and older prioritize expanding the production of oil, coal and natural gas.

The latter perspective aligns with the views of Republican president-elect Donald Trump, who has repeatedly dismissed concerns about climate change, labeling it “one of the great scams of all time” the weekend Hurricane Helene hit the Southeast.

But such rhetoric doesn’t play well with the majority of young people, regardless of their political identities.

Colleges Should ‘Talk About It’

According to the Lancet study, more than half of college-age respondents, including a mix of Democrats and Republicans from all 50 states, felt ignored or dismissed when they tried to talk about climate change; about 70 percent said they both want to talk about the dangers of climate change and for the older generations to understand how they feel.

However, the most helpful way to navigate climate-related mental distress “is to talk about it,” Lewandowski said. “When you have a place to do that, you can find that other people share your concerns, validate your concerns and there’s support for mutual connection.”

Colleges and universities offer a natural forum to not only air those frustrations, but also educate students about why wildfires, floods and hurricanes like Helene are happening with more frequency and intensity and what they may be able to do about it in the decades to come.

That’s what John Hildebrand, an oceanography professor at the University of California, San Diego, is hoping to accomplish through teaching a course on climate change and society this semester, which is one of about 40 courses that fulfills UCSD’s new undergraduate climate change education requirement.

“This generation of college students is going to be here for a long time, and it’s going to be a different world 50 years from now,” he said. “We should all recognize that this generation is going to have to deal with it and they need the tools to do that. Part of that is understanding the science behind it, how it interacts with the social organizations we have and the tools we have to fix it.”

As part of his class, students engage in futuristic role-playing, as, for example, a city planner in 2050 Los Angeles trying to keep rising sea levels from destroying the airport and certain neighborhoods.

“It’s not just [telling students] that these bad things are going to happen and there’s nothing you can do,” he said. “Whether they like it or not, there will be a role for them to mitigate the impact.”

But the implications of a warming climate for higher education institutions aren’t “anything new,” said Kim van Noort, chancellor of UNC Asheville, who’s been confronting natural disasters on university campuses for decades.

In 2005, the University of Texas at Arlington, where van Noort previously served as associate dean for academic affairs, took in faculty and students displaced by Hurricane Katrina. She was working at the UNC system office after Hurricane Florence hit North Carolina’s Outer Banks in 2018 and helped guide the cleanup efforts at UNC Wilmington.

“Anxiety is natural no matter what disaster happens—no matter what point in time,” van Noort said, noting that as climate events have become more severe, she’s focused on “talking openly with students and our community about the ways we are working to mitigate future issues.”

Before Helene hit UNC Asheville in September, the university was already making strides to prioritize sustainable infrastructure and climate education, aiming to become carbon neutral by 2050 and launching a master’s degree in climate resilience.

An aerial photo of UNC Asheville, facing the French Broad River and surrounded by the Blue Ridge Mountains.

UNC Asheville

“We knew the hurricane was coming and its potential impact on us, but we had had a week of record-breaking rainfall before the storm hit,” van Noort said. “We did not anticipate the levels of flooding. We knew the night before that things were going to be significantly worse than we had anticipated.”

‘Nurturing’ Mental Resilience

After the hurricane, the university launched a resiliency project, which includes a plan to involve students in building wells, cisterns and solar grids designed to withstand future severe flooding and power outages. It’s also part of an effort to expose them to opportunities to transfer climate anxiety into action—possibly even a career—and, at the very least, build personal resilience.

“I think students will want to come here and be a part of what we’re doing,” van Noort said. “It’s not just about the physical resilience of our buildings, it’s about the resilience of our people and the ways in which they feel equipped to handle natural disasters like this.”

And once the trees are cleared and the campus fully reopens, she said “nurturing” that “mental resilience” will increasingly become “a part of what we talk about” in the context of climate resilience.

One of those efforts got underway at UNC Asheville soon after Helene hit the campus. The university organized virtual individual and group counseling sessions for students navigating the logistics of Helene’s aftermath and the larger realization that not even the Blue Ridge Mountains can shield Asheville from a hurricane.

“The night after the storm, things were so hectic that I didn’t hear too much,” said Owen James, a senior at UNC Asheville who hunkered down on campus during the storm. But after everyone evacuated, the conversation quickly turned to frustration and anxiety about what the future may hold.

“People were reflecting on how a hurricane made it all the way here,” he said. “This is the reason why we need to be aware of things and make concrete changes to ensure that something like this doesn’t happen again.”

But that sense of urgency isn’t limited to the students at UNC Asheville, the University of South Florida or any of the other colleges that had to close during this year’s hurricane season.

Anxiety—and the realization that climate policy intersects with other social justice movements—is part of what pushed Rhea Goswami, a junior computer science major at Cornell University, to found the Environmental Justice Coalition in 2021.

“Climate anxiety is what keeps me going,” said Goswami, who is also a member of the Climate Mental Health Action Network’s Gen Z Advisory Board.

“We need more collective action. Nothing is going to fundamentally move the needle if one person does it,” she said. “If I can get one more person involved in the movement, that’s way better than just sitting on the sidelines.”