You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

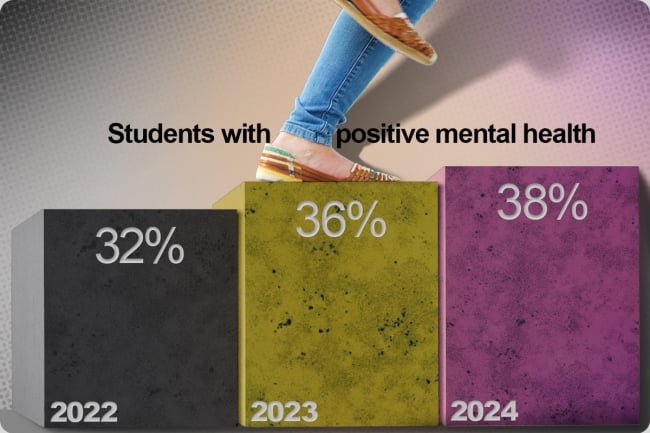

The share of students who show positive mental health is up from 2022, according to a new Healthy Minds study.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | m-imagephotography/iStock/Getty Images/The Healthy Minds study

Student mental health—long a top concern of higher education leaders—now appears to be improving, according to the latest edition of the annual Healthy Minds study. It found that 38 percent of undergraduates surveyed in the 2023–24 academic year experienced moderate or severe depression symptoms—down from the peak of 44 percent two years prior.

To be sure, the decrease is relatively slight, and the share of college students experiencing depression still hovers slightly above pre-pandemic rates: In fall 2019, 36 percent of students reported depressive symptoms.

But it’s the second year that the number has dropped, signaling that the downward movement might be a trend rather than an anomaly.

The data comes from latest iteration of the Healthy Minds study, the largest study of college student mental well-being in the country. With principal investigators at four different universities, Healthy Minds surveyed more than 100,000 undergraduates on mental health struggles, stigma and treatments.

The results show that it’s not only depression that has declined; rates of eating disorders dropped one percentage point over the past two years, nonsuicidal self-harm dropped three percentage points and suicidal ideation dropped two percentage points.

Perhaps most strikingly, rates of positive mental health—evaluated using something called the Flourishing Scale, which inquires into factors like students’ satisfaction with their relationships, self-esteem and optimism—have increased, rising from a low of 32 percent in 2022 to 38 percent this year.

“The reason why we started to [measure] this is because the absence of negative mental health didn’t necessarily mean students were feeling really positive about things,” said Justin Heinze, an associate professor of health behavior and health equity at the University of Michigan and the principal investigator on the Healthy Minds Study. “It’s really exciting because [that increase] doesn’t just mean bad things are going away.”

He noted that while data shows postsecondary students’ mental well-being moving in a positive direction, the number of students suffering from symptoms of mental illness remains high.

“I still see that as one in eight students reporting suicidal ideation in the last year, so I take all of these with a grain of salt and think about the millions of students still facing challenges we need to address,” he said.

Educating the Public

There’s no way to tell for sure what factors might be contributing to the improvements in students’ mental health. Heinze said it could help that they are now years removed from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many suffered from social isolation, difficulties with online learning and fear and uncertainty about the virus. But the decline in youth mental health predates the pandemic by years; according to Healthy Minds, depressive symptoms increased almost every year from 2015 to 2022.

The improvements could also be attributed in part to the efforts of universities and outside advocacy organizations to bring awareness to the youth mental health crisis and develop resources for struggling students.

“I like to think it’s the work of [National Alliance on Mental Illness] and other organizations like [The Jed Foundation], Active Minds, the Child Mind Institute and [the National Institutes of Health]. There are so many of us working so hard just to educate the public to get the word out about youth mental health that it might finally meet the need,” said Jennifer Rothman, director of youth and young adult initiatives at NAMI.

She added that it’s the first time in her long career in mental health that she’s seen such declines in students’ psychological distress. “I honestly can’t say if I think it’s going to continue—I hope it does.”

Certainly, awareness of mental health services is increasing; 76 percent of respondents said they were at least somewhat cognizant of the mental health resources are available on campus, the highest rate since the fall of 2019.

Not every data point in the study was quite so encouraging, however; the proportion of students who said they thought their classmates would think less of someone who received mental health treatment was 41 percent—slightly higher than last year.

“There’s so much more perceived stigma,” said Rothman. “What we have heard, over and over again, is that young people would be more than happy to help a friend or family member or an acquaintance who came to them and said they were struggling with their mental health … but they stigmatize against themselves for seeking treatment.”

Although it has declined slightly from 2022, the percent of students who said they currently need help managing their mental health and negative feelings remains extremely high at 78 percent.

Both Heinze and Rothman said that might not be such a bad thing. It could indicate that there is a population of students who have received some treatment but recognize that their mental health journey is still underway. It could also indicate that a rising share of students want help improving their mental health even if they aren’t in crisis or suffering with symptoms of depression.

“I think a big percentage recognize that they have concerns,” Heinze said. “Probably, that speaks to [students’] general awareness of their own mental health.”