You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University

As the academic year comes to a close, the wave of pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli protests that consumed college campuses across the country may be dying down, but discussions of their effect on anti-discrimination, free speech and academic freedom policies are not.

Administrators continue to face investigations from lawmakers on Capitol Hill who allege they have failed to protect Jewish students and faculty from antisemitism. Meanwhile, many students and faculty say punishing instructors for discussing controversial issues in class—never mind calling in law enforcement to sweep encampments—is an overstep.

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, a nonprofit research, litigation and public education group focused on threats to freedom of speech and the press, has dedicated the second season of its podcast series, Views on First, to exploring the impact of the Israel-Hamas war on academia. Topics range from the specific, such as the origins of the Columbia protests, to the sweeping, such as the historic tensions between anti-discrimination and free speech law.

Knight First Amendment Institute

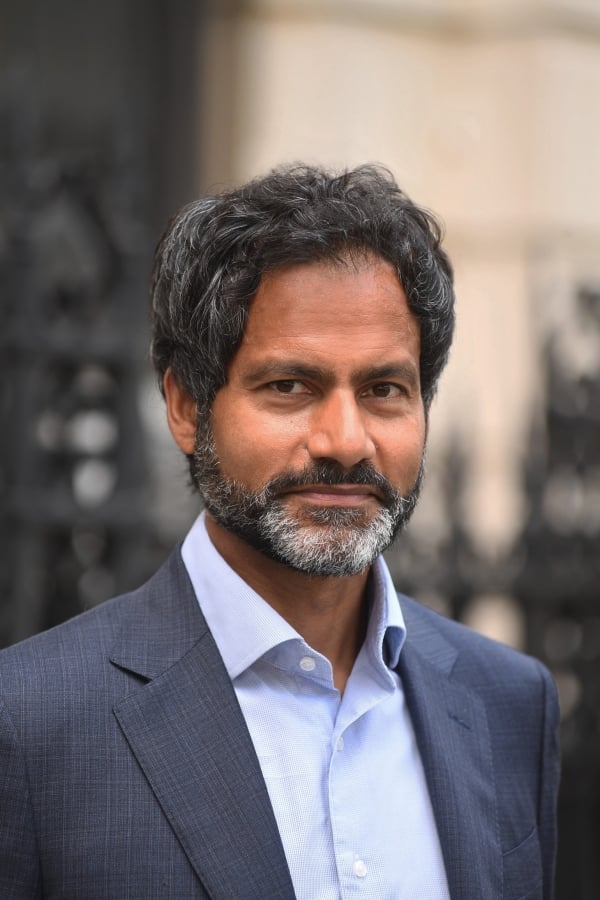

Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the institute and host of the podcast, responded in writing to a series of questions from Inside Higher Ed about the state of First Amendment rights in higher education and the ethos of the campus protest movement.

The interview, lightly edited for length and clarity, follows.

Q: What do you hope that the second season of Views on First and its particular focus on campus speech amidst the war in Gaza will achieve?

A: There’s been a wave of censorship and suppression here in the United States in the months since the October 7 attacks—a lot of it on university campuses. We launched this project because we wanted to consider whether our system of free speech was failing us, and to explore what might be done to better protect the space for inquiry, debate and dissent.

Q: Based on your conversations on the podcast so far, to what extent has controversy over the Israel-Hamas war actually impeded or repressed free speech on college campuses?

A: There’s certainly been a great deal of suppression and attempted suppression of one kind or another. Universities have suspended student groups, imposed new restrictions on protests and demonstrations on campus, and canceled film screenings and events. Alumni have sent letters demanding that universities fire faculty said to have celebrated the attacks. Students have torn down posters and shouted-down speakers … A congressional committee berated university presidents for their failure to suppress what legislators described as calls for genocide … And many universities called in the police to end protests that were overwhelmingly peaceful. I could go on.

But there’s a kind of paradox here, too—and this is something I discussed in the podcast’s first episode with Genevieve Lakier, who is a First Amendment scholar at the University of Chicago. On one hand, there’s this extraordinary wave of censorship and suppression—reminiscent in some ways of what we witnessed during the McCarthy era. But on the other hand, debate in the United States about Israel and Palestine is surely more open and uninhibited than it’s been in decades. There are demonstrations and protests every day. There’s a ton of political commentary on this topic in the newspapers and on television and on social media platforms. The range of ideas being expressed now is much broader than it’s been in a very long time. Professor Lakier suggested to me that many of the efforts at suppression are a reaction to the sudden opening-up of this long-suppressed debate. That sounds right to me.

Q: One of your episodes talks about the long-held tension between anti-discrimination law and the First Amendment, and the blurry line between free speech and hate speech. Has the war shifted conversations on the difference between the two at all, particularly on college campuses, and if so, how?

A: Well, let’s start by recognizing that the Supreme Court has understood the First Amendment to protect hate speech. The First Amendment, as the Supreme Court has interpreted it, protects a great deal of speech that many of us would find offensive and even abhorrent. That’s not to say the First Amendment doesn’t have limits … But the mere fact that speech is hateful doesn’t take it outside the First Amendment’s protection. The consequence is that public universities, which are bound by the First Amendment, can’t suppress speech merely because it’s hateful, or because some listeners say it’s hateful. And while private universities aren’t bound by the First Amendment, most of them give very broad protection to speech … because they want to foster intellectual environments in which no idea is immune from scrutiny and challenge.

All of this said, universities have to reconcile their commitments to free speech and academic freedom with their commitments to equality and inclusion. And all universities have a legal obligation, under federal anti-discrimination law, to protect students from discrimination and harassment. My sense is that … uncertainty over the meaning of federal anti-discrimination law, and fear of liability, has led some universities to suppress speech that the First Amendment certainly protects.

Q: Do you consider “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” an example of free speech or hate speech? How should institutions handle it when campus constituents have opposing views of the same phrase?

A: I don’t think a political slogan like this can fairly be said to have a single meaning. People use phrases like this in different ways, and people hear them in different ways, too. That’s true of Palestinian symbols and slogans, and it’s true of Israeli ones as well. Some Jewish students hear “river to the sea” as a call for genocide. Some Palestinian students see the Israeli flag as a symbol of their people’s dispossession and even elimination. The question of what universities should do when campus constituents have radically different understandings of a particular slogan or symbol isn’t easy to answer. I spoke with Michael Dorf, a constitutional scholar at Cornell Law School, about this; he pointed out that the courts have been struggling for many years to sort out whether it’s the speaker’s perspective or the listener’s perspective that should determine whether speech is constitutionally protected. The one thing I’d say is that if universities made a rule of deferring to listeners—that is, of adopting listeners’ interpretations of speakers’ speech—they’d end up suppressing a lot of speech.

Q: In the context of higher education, free speech and academic freedom tend to be closely tied—is there a distinction between the two? And if so, how would you define it?

A: “Academic freedom” is sometimes understood to refer to the right of universities to determine for themselves—without outside interference—who can teach, what can be taught, how it should be taught, and who should be admitted to study. The phrase is also sometimes understood to refer to the right of individual faculty members to direct their own research, and to teach as they see fit, within disciplinary boundaries. Jeannie Suk Gersen, a Harvard Law School professor who has been a prominent defender of academic freedom, told me that she thinks of academic freedom as a kind of “collective good.” Sometimes academic freedom is conceived of as a value or right independent of free speech, and sometimes it’s conceived of as an aspect of free speech. The Supreme Court has made some lofty pronouncements about academic freedom, but the pronouncements are imprecise and unsatisfying.

Q: Do you think academic freedom is being threatened by administrators’ and/or lawmakers’ response to the protests?

A: Academic freedom is under pressure right now from a lot of different directions—from the government, donors and alumni, university administrators, and political movements and ideas on the right and the left, though in different ways and to different degrees. I found it alarming to see legislators call on university administrators to suppress peaceful protest on campus, and to demand that they sanction professors for their speech—and even more dispiriting to see some university administrators accede to legislators’ demands. I understand the pressure that university administrators are under, but universities can’t afford to treat free speech and academic freedom as negotiable. They have to make a strong defense of these freedoms, because ultimately it’s these freedoms that enable universities to play their distinctive and vital role.

Q: I know that the situations have varied widely from campus to campus, so for this question let’s narrow in on what you know best—the protests at Columbia University. Have President Shafik’s responses, including calling in law enforcement, been justified?

A: Columbia’s leadership had to make quick decisions, under a lot of pressure, in relation to a situation that was very complex and constantly evolving. I don’t envy them. But they made some serious errors, as leaders at many other universities did. The Knight Institute sent two letters to Columbia’s administration about its response to the student protests. In the first letter, which we sent in November 2023, we raised concerns about the University’s decision to suspend two student groups—Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace.

We sent the second letter in April 2024, after President Shafik and the Co-Chairs of Columbia’s Board of Trustees had testified before Congress, and after Columbia’s administration had called in the police to dismantle a student encampment. We expressed concern that Columbia’s decisions and policies had become disconnected from the values that are central to the University’s life and mission—including free speech, academic freedom and equality—and we called for an urgent course correction. With respect to the decision to call in the police, we noted that the University had a legitimate interest in enforcing reasonable restrictions on the time, place and manner of protests—and that the encampment was in violation of those rules. We also observed, though, that the University’s own regulations provide that the police should be called on to end a campus protest only when there is a clear and present danger to the functioning of the University. We didn’t think the encampment presented that kind of danger, and we said so. It’s notable, I think, that the police themselves said that the students were protesting peacefully and offered “no resistance” when they were arrested.

Q: Campuses have long been centers of protest and political debate. Is there anything in particular Inside Higher Ed readers should note that makes this wave of protests and the responses to them different than, say, those during the Vietnam war?

A: I just read the report of the Cox Commission, which was a fact-finding commission appointed to investigate the events at Columbia in May 1968. I was struck by some of the similarities between the events of 1968 and the events that have unfolded over the past eight months. One of the students’ principal complaints in 1968 had to do with the University’s perceived complicity in the war in Southeast Asia—students were upset that the CIA was recruiting on campus, and that the University had not been fully transparent, in their view, about links with the military. The campus was starkly divided, and university administrators feared that there would be violence between protesters and counterprotesters. The ferment on campus was closely connected to a larger, national political debate about the war. And the conflict between students and the administration escalated when students perceived the University to be acting arbitrarily or autocratically. There are lots of parallels here. Of course, there are differences, too. One thing that’s distinctive about the current wave of protests is the extent to which they’re tied up with questions about language. There’s this chasm between what speakers think they’re saying and what listeners think they’re hearing.

Q: I know it's impossible to predict the future, but when you look ahead to the next academic year, what kind of campus climate do you anticipate? And do you have any thoughts on how this current season of events will impact free speech in academia?

A: I really don’t know what to expect, but it’s safe to assume that students will continue to care deeply about what’s happening in the world around them. They’ll continue to organize, gather and speak out, and so there will be protests and counterprotests, perhaps especially in the weeks before and after the November election. The fall will bring a new set of challenges, I’m sure.