You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Indiana University administrators’ sudden changes to a 1969 policy designating an official “assembly ground” for student protests have sparked backlash.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Indiana University

Dunn Meadow, a 20-acre green plot on Indiana University Bloomington’s campus, has been an official assembly ground for student protests since 1969, when the university’s board of trustees designated it a “public forum” for IU community members.

“Students, staff and faculty of the University may express any point of view on any subject in the Assembly Ground, with or without advance notice, within the limits of applicable laws and regulations. This decision enhances the rights of free speech and assembly,” the 55-year old policy reads. It also protects the use of “signs, symbols or structures” on the meadow “as an appropriate exercise of the right of expression,” as long as they’re removed between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m.

So when student protesters sought to set up a pro-Palestinian encampment last Thursday morning, Dunn was the obvious site.

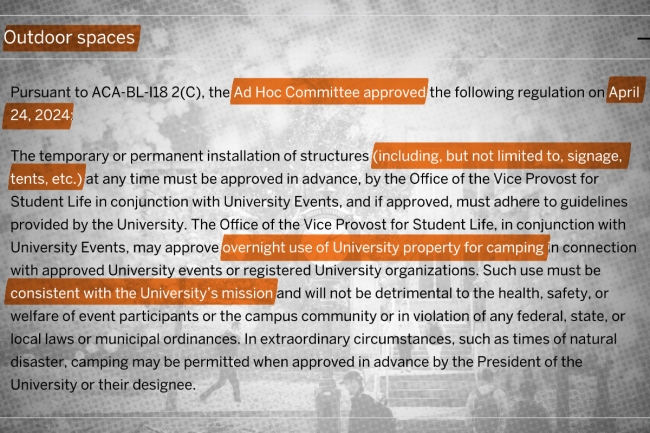

But the night before, a small group of administrators—including president Pamela Whitten and provost Rahul Shrivastav—learned of their plans. Shrivastav quickly formed an ad-hoc committee and changed the assembly ground policy to prohibit the “temporary or permanent installation of outdoor structures” without prior administrative approval. The addendum specifically prohibited the use of “signage” and “tents.”

There was no university-wide email or public announcement—only a time-stamped update under a drop-down menu on the university’s undergraduate events website, and a physical copy of the new policy posted in the grass where students began setting up the next morning.

Later that day, university leaders called in Indiana state troopers to dismantle the encampment. Student journalists reported that police dragged, pushed and zip-tied student protesters, 33 of whom were arrested for trespassing; state police leaders confirmed that officers “with sniper capabilities” were perched on rooftops overlooking protesters on the quad below. Dozens of students were banned from campus for violating the new policy.

In an email to IU faculty later that afternoon, Whitten defended her decision to change the policy.

“The change was posted online and at Dunn Meadow this morning, and participants were told repeatedly that they were free to stay and protest, but that any tent would need to be dismantled,” Whitten wrote. “Given the expectation of a high number of external participants, Indiana State Police was brought in as a law enforcement partner.”

The decision has sparked backlash not only from student protesters, but from faculty, free speech advocates and local officials who observed the change. Former Bloomington Mayor John Hamilton, who visited the encampment after students resumed their protest Friday night, told the Indiana Daily Student he felt the policy change was “inadvisable, and likely unconstitutional.”

Steve Sanders, a constitutional scholar and professor at IU’s Maurer School of Law, said the move was, in his view, an obvious violation of the groups’ right to peaceful assembly and protest.

“It is entirely inferable, in this case, that this policy was changed in anticipation of the pro-Palestinian protesters’ specific conduct and speech. That’s where this becomes a First Amendment issue,” he said. “You can change the rules, but you can’t change them to target or disadvantage a particular group.”

An IU spokesperson responded to a list of questions from Inside Higher Ed with a copy of Whitten’s email explaining the change to faculty, and another she sent to students on Sunday afternoon. He also encouraged faculty and students facing discipline to “engage in the appeals process,” during which he said their campus bans would be suspended “in nearly all cases.”

Adding Fuel to a Free Speech Fire

The Dunn Meadow policy change isn’t the first time Indiana leadership has been roiled by free speech controversies over pro-Palestinian sentiment this year.

Two weeks ago, the university’s faculty council passed a vote of no confidence in Whitten and other administrators over their response to lawmakers’ demands to crack down on perceived antisemitism on campus.

The protest policy controversy has only inflamed the tensions. Danielle DeSawal, president-elect of the IU Bloomington Faculty Council, wrote in an email to faculty on Monday that the council was not involved in the ad-hoc committee’s policy change or alerted to it beforehand. She met with Whitten on Sunday to ask for the policy to be revoked.

“Two short-term goals were to have the addendum revoked and gain assurance that the Indiana State Police would not engage with our community,” DeSawal wrote in the email, which Inside Higher Ed reviewed. “The signs in Dunn Meadow were not clear on how to gain permission for temporary or permanent structures, the approval process (when known) was not able to be completed in an efficient manner, and the individuals who have been arrested in Dunn Meadow have primarily been affiliated with IU.”

Outgoing IU Faculty Council president Colin Johnson also wrote an open letter on Monday excoriating Whitten for the policy change, which he said sabotaged a uniquely prescient free speech protection by undermining the assembly ground principles laid out in 1969—principles which, he believed, many universities could learn from at a time of heightened conflict between university administrators and student activists.

“Every other campus in the country did not have the wisdom to acknowledge and embrace the inevitability of public protest on a university campus in a way that safeguards the right of freedom of expression while also minimizing disruption to other ongoing activities,” Johnson wrote in an open letter to fellow faculty members, which was obtained by Inside Higher Ed. “Yet despite being handed a ready-made solution to the supposedly intractable challenges that campuses across the country are currently facing … the Whitten administration decided instead to lean in to its own impulsiveness.”

Protest Policies Under Pressure

The pro-Palestinian student protest movement that began in October and exploded in April is revealing the contradictions and limitations of current campus speech policies across the country.

A recent survey of college and university presidents conducted by Inside Higher Ed and Hanover Research found that 21 percent of institutional leaders believe recent world events have stressed their campus speech policies to the extent that those policies may need revisiting. In a similar annual survey of university provosts fielded in February and March, 39 percent of respondents said the same. And as protests have become more disruptive in the past month, college leaders have varied widely in how they interpret and enforce policies covering student conduct.

Indiana isn’t the only college to adjust its policies on the eve of protest. On Thursday morning, one day before a planned student encampment at Northwestern, university president Michael Schill announced an “interim addendum” to the university’s code of conduct, immediately banning tents and other “temporary structures” on campus grounds, except those pre-approved for school events.

And in October, Columbia University administrators changed their policies around large group events shortly after large pro-Palestinian protests drew media attention—and a few weeks later, used the new language to suspend the university’s chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine.

Geoffrey Stone, a University of Chicago law professor and one of the chief authors of the Chicago Principles of Free Expression—a set of best practices for campus speech policies that have been adopted by over 70 colleges and universities—said the changing policies could indicate that administrators are targeting specific political groups.

Or, he said, it could just be a sign that their policies were not equipped to deal with the anti-war encampment movement, and they’re scrambling to update them to prevent academic disruption.

“It’s perfectly possible that this is a change in a rule that is designed to disadvantage a particular message that the institution does not want to see conveyed on its property, and that would be impermissible,” he said. “The other side of the argument would be, the rule we had in the past did not really anticipate situations like the ones that we’re now confronting … if I were writing these policies 20 years ago, I could not have anticipated the importance of tent policies.”

Sanders, who is also associate dean of the Maurer School and has served in many capacities during his nearly 40 years at IU, said he believes the unilateral policy change reflects a number of larger issues surrounding the recent denigration of university norms such as shared governance and a commitment to free expression above other priorities like donor appeasement.

“It really reflects the larger corporatization of higher ed, and the shift in administrators acting not as stewards of academic institutions but as corporate managers,” he said. “Unlike the administrators and general counsel who mentored me, they’re not interested in shared governance anymore.”

Stone said he wasn’t sure what motivated administrators like Whitten to change their policies so suddenly. But the influence of large donors and influential alumni constituencies has ballooned in recent years, and he worries it may be having undue influence on evolving campus speech policies.

Sanders said that donor influence has been a major issue at Indiana, and that the very nature of the policy change itself—implemented through the abrupt creation of a small administrative committee with unilateral decision-making power—showed that the university cared more about preventing the encampment and appeasing outside parties than developing responsive new protest policies.

“When you call something an ad hoc committee, that basically says ‘This is not guided by any enduring principles. We’re making a decision for the moment, focused on this particular group and this particular event,’” he said. “It’s not how you imagine principled decision-making should work.”

Stone said that he hopes universities are thoughtful and, when appropriate, restrained in enforcing protest policies, whenever they were created, in the weeks ahead.

“Universities have a legitimate right to enforce these policies, and a legitimate interest in their ability to function as academic institutions, [and] ensure the safety of community members, even in campus aesthetics,” he said. “But we always exercise discretion in deciding whether or not to enforce a rule...and in this context, I’d bend over backward to allow the students to engage in expressive activity if it is not appreciably disruptive.”

On Sunday, Indiana students and faculty gathered again on Dunn Meadow to protest the arrests and punishments of their peers. Riot police were again called in to the once-sacred assembly ground, and another 23 students were arrested.