You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

An antitrust lawsuit against 17 elite colleges unearthed explicit evidence of admissions favoritism for wealthy applicants.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | arlutz73/iStock | Alex Wong/Getty Images | Aaron Yoder/iStock/Getty Images

Late Friday, Johns Hopkins University and the California Institute of Technology settled in a federal antitrust lawsuit accusing 17 highly selective universities of illegally colluding to fix financial aid formulas and overcharge students.

The agreement leaves only five of the original 17 defendants named in the 2022 lawsuit still fighting: Cornell University, Georgetown University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Notre Dame and the University of Pennsylvania. All five have denied wrongdoing and continue to defend their practices.

The colleges were all at one point members of the 568 Presidents Group, a consortium of need-blind institutions that were allowed to collaborate on financial aid formulas with immunity from federal antitrust laws. The group disbanded in 2022, when the congressional exemption that led to its creation in 1998 expired.

The lawsuit’s main claim is that the group flouted the antitrust laws by colluding to limit financial aid awards, preventing expensive bidding wars over top students.

But in documents filed to support the lawsuit, a trove of evidence has been made public that raises separate but related questions about the porous borders between these universities’ fundraising arms and their admissions offices. They show that some institutions identified and admitted certain students based on family wealth or connections, regardless of their qualifications.

According to the documents, several of the universities named in the lawsuit kept “special interest” lists of applicants from wealthy families or with ties to corporate or political power players, and they admitted students based on affluence and donor capacity, even when they fell short of typical academic standards. A 2021 memo from Georgetown notes that the policy “allows the University to consider special circumstances in the admission of some qualified candidates who might not be admitted competitively … in exchange for the opportunity the University will have to develop a better association with this family or sponsor.”

We need to do a better job of enlisting the support of America’s wealthiest families.”

—From a 2021 Georgetown internal memo

The goal of these lists, as described in a 2021 memo from Georgetown included in the court filings, was simple: to raise money.

“The University is under-funded and under-endowed and we need to do a better job of enlisting the support of America’s wealthiest families and corporations in assisting us,” the memo reads.

Inside Higher Ed set out to answer the question of whether these universities—among the nation’s wealthiest—continue to use special interest lists. Of the five remaining defendants, only MIT outright denied it.

Tags and ‘Massive Allowances’

It’s no great secret that highly selective universities give preferential treatment to certain applicants. Most of the colleges included in the original lawsuit openly advantage legacy applicants, for instance. And members of the 568 group are by no means the only institutions to give admissions preference to well-connected students; a recent investigation by The Assembly uncovered evidence of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill board members texting admissions officers to push for specific applicants.

But the court filings paint a clear picture of the influence that board members, donors and wealthy families have exerted on admissions offices. They reveal lists of dozens of applicants—compiled by the university president in Georgetown’s case, and the development or donor relations staff in others—who were then either recommended for admission or tagged with a label recommending consultation with the fundraising team. According to the documents, these lists were often made without regard for the applicants’ academic qualifications.

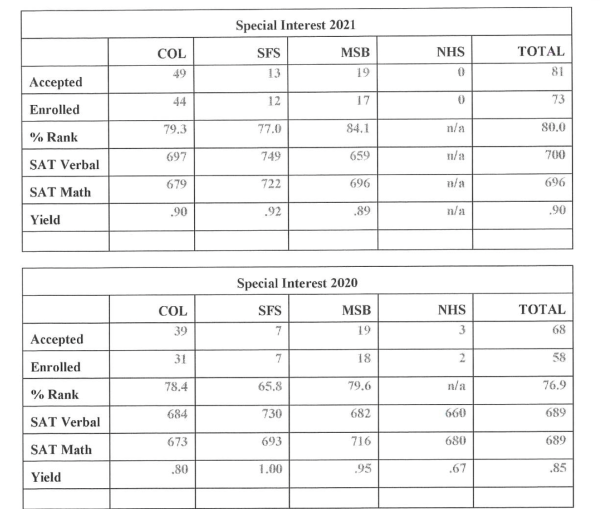

At Georgetown, for instance, from 1993 to 2021, 2,026 students on special interest lists were admitted to the university; of those, 1,747 enrolled, according to a review of court documents by Inside Higher Ed. And the number of students accepted off the special interest list increased steadily over the years, from 55 in 1993 to 81 in 2021, the last year Georgetown evidently used the tags.

One document, apparently a spreadsheet to track special interest applicants, details the connections that landed students on the list. One student’s father is identified as “a longtime friend of Mr. [Kevin] Warren,” a member of the Georgetown Board of Directors. Another’s parents were “friends of” former Georgetown president Lee O’Donovan. Many of the details are censored for privacy reasons, but certain phrases appear repeatedly: “applicant’s father is Chairman and CEO of” a redacted company, or “head of” a redacted organization—or, in one case, a redacted politician’s chief of staff.

A document detailing Georgetown university’s use of special interest lists as recently as 2021, from court documents.

Another document reveals the Georgetown advancement office’s calculations for the “donor capacity” of prospective students’ connections. Some are determined to have a capacity of tens of thousands of dollars; others, tens of millions. In responses to questions from Inside Higher Ed, a Georgetown spokesperson declined to say whether the university ever used special interest lists in admissions or to address specific claims made in the documents.

“We believe the university has acted responsibly and always with the goal of only admitting students who will thrive in, contribute to and further strengthen our community,” the spokesperson wrote.

Notre Dame also calculated donor capacity; in one court filing, officials acknowledged that it “admitted students based on factors which included the applicant family’s donation history and/or capacity for future donations.”

Notre Dame admitted 163 applicants off its “university relations” list in 2012, including 38 who fell well below its typical academic standard. Those applicants were classed in an admissions category that normally would have led to rejection; admitting them, then–associate vice president for undergraduate enrollment Donald Bishop wrote in an email included in the court documents, amounted to “massive allowances to the power of family connections and funding history.”

Bishop added that he hoped next year, “the wealthy” would “raise a few more smart kids!”

Documents show that Cornell kept special interest lists as well, and MIT maintained “a list of applicants” for admissions that included children of wealthy donors and others with a “development link.” Penn tagged certain students as “BSI,” meaning “bona fide special interest” (Penn exited the 568 Presidents Group in 2020, citing a desire to be more generous with financial aid).

Spokespeople for Cornell, Notre Dame and Penn all declined to answer specific questions from Inside Higher Ed about the existence and use of such lists and preferences.

“Plaintiffs’ whole case is an attempt to embarrass the University about its purported admission practices on issues totally unrelated to this case,” a Penn spokesperson wrote. “Penn does not favor in admissions students whose families have made or pledged donations to Penn, whatever the amount.”

Every place I’ve ever worked, and every place I could imagine working, had lists.”

—Jonathan Burdick, former vice provost for enrollment, Cornell University

In an email to Inside Higher Ed, MIT spokesperson Kimberly Allen said that the university never used special interests lists or tags for applicants recommended by donors or board members.

But evidence from the court documents suggests that officials blurred the lines between admission and advancement at least twice.

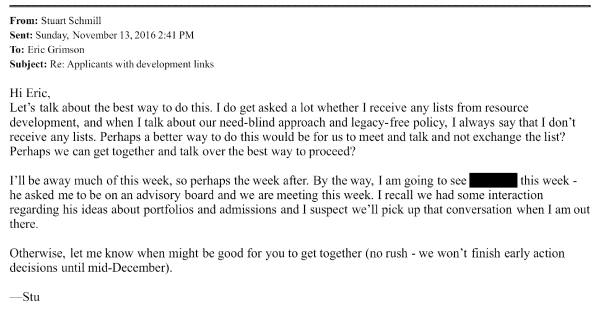

A court filing showed MIT Corporation chair Robert Millard exerted pressure on the university to admit two children of a wealthy former colleague, whom admissions director Stuart Schmill said, “We would really not otherwise have admitted.” And in a 2016 email to Schmill, Eric Grimson, MIT’s chancellor for academic advancement, wrote to ask whether a list of applicants with “parents who are already significant donors or are in the pipeline” would be useful.

“When I talk about our need-blind approach and legacy-free policy, I always say that I don’t receive any lists,” Schmill responded. “Perhaps a better way to do this would be for us to meet and talk and not exchange the list?”

An email between MIT officials, from court documents.

Allen said the university would address the lawsuit’s specific allegations in a court filing later this month, but she said the examples in the filings were “isolated cases” with no connection to “the potential for philanthropic gifts.”

“MIT has no history of wealth favoritism in its admissions,” she wrote. “MIT’s admissions office knows that Institute leadership supports them in making tough calls that come with high standards.”

Whether the remaining universities continue these practices or not, the case itself may have already damaged their public images—and those of unwitting colleges across the country.

Angel Pérez, president of the National Association for College Admission Counseling, said the reverberations are one of the most unfortunate consequences of the lawsuit. With the memory of the Varsity Blues admissions scandal still relatively fresh in public memory, allegations of universities secretly prioritizing the children of the rich and powerful is likely to further erode public trust in the sector, even at less selective universities where “donor capacity” is unlikely to be a factor.

“The things that have come out about practices at a few institutions are going to have repercussions for all institutions,” Pérez told Inside Higher Ed. “There’s going to be less trust in the process and less trust in higher education.”

A Widespread ‘Not Best Practice’

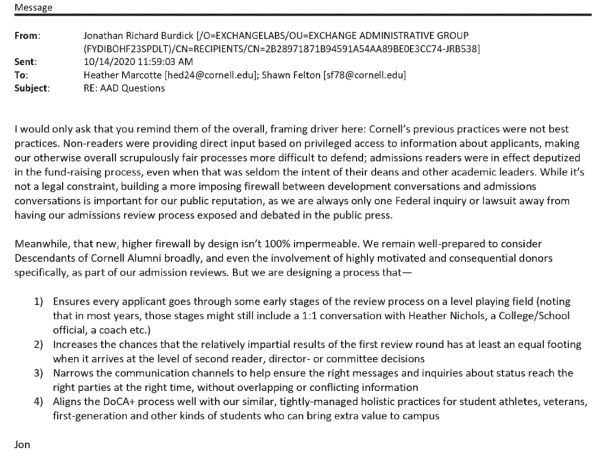

In October 2020, Jonathan Burdick, Cornell’s then–vice provost for enrollment, wrote an email to two admissions directors about the involvement of the development office in admissions decisions. In the email, obtained by Inside Higher Ed and made public in the court filings last month, Burdick described Cornell’s history of donor involvement in admissions as “not best practices.”

“Non-readers were providing direct input based on privileged access to information about applicants, making our otherwise overall scrupulously fair process more difficult to defend,” he wrote. “Admissions readers were in effect deputized in the fund-raising process.”

He also presciently worried about the hit Cornell’s public image might take if those practices came to light.

“We are always only one Federal Inquiry or lawsuit away from having our admissions review process exposed and debated in the public press,” he wrote.

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed on Friday, Burdick, who left Cornell in 2023, said he wasn’t aware that his email was included in the court filings. But he stood by what he’d written and said that when he first joined Cornell in 2019, preferential treatment for certain applicants was deeply woven into the admissions process.

“Cornell’s readiness to manage that was not good when I got there,” he said. “The actual providing of a list, saying, ‘Here’s the names of the ones we care about the most, please say yes to them’—that conversation was formal and embedded in Cornell’s practices.”

Burdick’s 2020 email to Cornell admissions directors, from court documents.

Though university officials declined to say when or whether they stopped using special interest lists, Burdick said Cornell did away with them in 2019, the year he joined the university. One of his first major actions, he said, was to develop a policy to erect a “more imposing firewall” between development staff and admissions officers.

The effort was ultimately a success. But while university leaders supported the policy change, facilitating donor influence on admissions decisions was deeply entrenched in the day-to-day work of the development office. It had become a “habit,” Burdick said, and one that was “a slog to get rid of.”

“I had to go many, many rounds with one major donor, whose expectation was that the big donation she had made was going to be enough to influence us to choose a student she knew,” he said, adding that the student was not admitted.

Burdick, who previously served in leadership roles at the University of Southern California and the University of Rochester, said that marking applicants based on their personal connections was common practice at those institutions as well.

“Every place I’ve ever worked, and every place I could imagine working, had lists,” he said. “The question was, at what time and in what way was the list you were carrying brought to the fore?”

When he was at USC—more than two decades ago, before its practices were rocked by the Varsity Blues scandal in 2019—he said the university president kept a list of donor’s children, athletes, legacy applicants and other special applicants in “a secret locked file cabinet” in his office; if any were going to be denied admission through the usual process, the list would often be used to supersede that decision.

“Every one of [the applicants on the list] would have a memo from the director of admission saying, ‘This is not a good idea.’ And the president’s office would send back a memo saying, ‘OK, we’re gonna do it anyway,’” he said.

Even at Rochester, Burdick said flagged applications denoting family wealth or a connection to a donor would sometimes make their way to his desk. He said he was never disillusioned about the role wealth played in college admissions—leaders’ intentions in raising money to fund things like financial aid were usually good, he said, even if the practices were questionable. But he hopes that the old habits, though they may die hard, do eventually die.

“The sincerity of universities’ intent is, I think, undoubtable. But do they have all their practices in a row? Not at all,” he said. “I think it probably exists more as an unintentional culture than it does as a practice, and more as a practice than it does as policy. But if exposing it is part of universities cleaning house for the next generation, I think that’s great.”

(This story has been update to correct Jonathan Burdick's previous place of employment from Rochester Institute of Technology to the University of Rochester.)