You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

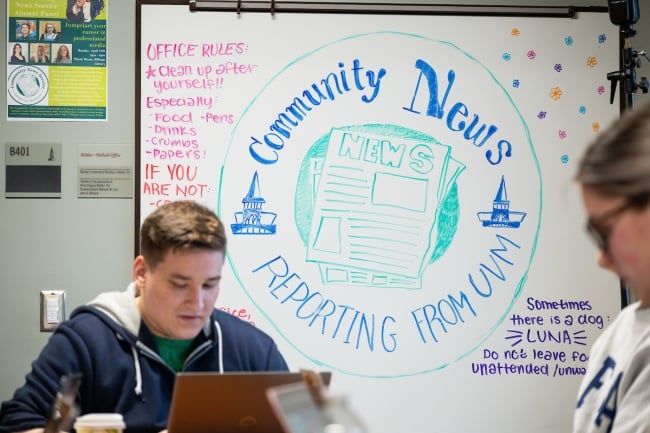

Students working at University of Vermont’s Center for Community News, which supports similar programs at colleges and universities across the country.

Andy Duback/UVM

Throughout high school, Charlotte Oliver wanted to become a journalist. But there was no journalism major at the University of Vermont, where the New Jersey native ended up enrolling.

Oliver declared an interdisciplinary Global Studies major, which she loves, yet never lost the itch for storytelling.

“News still just sounded really appealing, because there’s such a clear civic purpose to it,” she said. “What kept me engaged in the idea all those years were really interesting anthropology and history classes that taught me how important journalism is for posterity.”

When Oliver started searching for a reporting internship last fall at the start of her junior year, she came across UVM’s Center for Community News (CCN), and relished the chance to dive headfirst into the world of local reporting.

Initially launched in 2019 with funding from the university, the CCN was designed to be both a laboratory for students interested in journalism and a creative way to combat the shortage of local news coverage in parts of Vermont. It created a new minor that matches student reporters with faculty editors, enabling aspiring journalists like Oliver to learn from experience while also providing local news groups with vital reporting on under-covered beats.

Since 2022, the center has expanded beyond Vermont, becoming a leading national resource for similar programs coast to coast.

Now, with a recent donation of $7 million—$5.5 million from the Knight and MacArthur Foundations and $1.5 million from UVM donors and the College of Arts and Sciences—the CCN hopes to grow, not only by partnering with more colleges and news organizations but also inspiring more students to pursue a career in local journalism.

“It’s a triple win, in a sense,” said Richard Watts, founder and executive director of the CCN. “It’s good for the students to have real stories that are published. It’s good for the universities, because many of us have a public service mission to give back. And it’s good for local news, the media ecosystem, which has really collapsed.”

Indeed, the latest donation reflects a growing push to leverage higher education resources to protect the “fourth estate” of American democracy by re-energizing public news in underserved regions.

“When we started this teaching-hospital–type program at Vermont, we looked around the country to see who else was doing this and found some others, but nobody had connected them,” Watts explained. “The concept was, “Let’s enable these programs to build a community, learn from each other, and see if we can motivate more institutions to give this experience to their students, and contribute to local news.’”

Knight and MacArthur are part of the Press Forward Initiative, a group of 62 philanthropies aiming to invest a total of $500 million over the course of five years to local news outlets. The $5.5 million they donated is the largest known gift made to a university-led local news program so far.

Dale R. Anglin, director of Press Forward, was elated about the gift and said she hopes to see more donations like it moving forward.

“Right now, people often say, ‘I fund certain types of [news] outlets.’ In doing so, you’re funding at the end of the pipeline. The colleges are part of the people part of journalism,” she said. “I want to see foundations understanding that this should be one of the things you consider when you are funding in the journalism space.”

Deploying an ‘Army’

In an era when social media and political polarization have opened the floodgates of misinformation and the traditional advertising-based business model of journalism has been shattered by big tech, newsrooms across the country have shuttered at an alarming rate.

Since 2005, the U.S. has lost almost 3,000 newspapers and 43,000 journalism jobs, and 1,766 counties have been declared “news deserts”—areas with one or zero local newspapers—according to a 2023 State of Local News Report by Northwestern University’s Medill School.

Since its inception, the CCN has sought to combat this loss by mapping the landscape of more than 1,316 campuses located in or adjacent to those “desert” counties. The center has already identified and conducted research on more than 130 higher education institutions that boast local news programs, and fostered collaboration among the faculty who lead them. But there are nearly 1,200 that remain untapped.

With the latest gift, Watts said the center is hoping to flesh out its existing toolkits for new local news programs, plan more site visits and workshops and conduct an expanded benchmark study to capture the impact of student reporting.

For Christopher Drew, a 22-year New York Times reporter who now leads Louisiana State University’s statehouse news bureau, support from the CCN has been pivotal in guiding the development of a network in Louisiana to address coverage gaps beyond the capital of Baton Rouge.

“We had traditional, mainstream media for a couple of centuries. And we’ve had a whole second wave of nonprofit newsrooms. To me, the third wave is all these students at universities across the country,” Drew said. “There’s this army of journalism students out there and they’re our best hope.”

What the donation won’t be used for, Watts said, is providing sub-grants to entirely fund the launch of new programs.

“These programs have to be sustainable,” he said, “Ultimately, funding has to come from the university. We can help support it as it grows. But it has to be a college or university initiative.”

Active and Engaged

Researchers who have focused on local journalism, news deserts and rural media say it’s extremely helpful to have a clearinghouse center like the CCN, which is the first of its kind to quantify the phenomenon of university news partnerships.

Teri Finneman, an associate journalism professor at the University of Kansas, publisher of The Eudora Times and coauthor of the upcoming case study book, News Desert U, said the CCN’s work is “incredibly important,” not only in the macro sense of protecting American democracy but also at the smaller-scale human level of supporting hardworking faculty.

“A lot of people think that at universities, we have all the resources we need, and that just simply isn’t true,” said Finneman, who previously sat on the center’s board of directors. “There's a lot of help that is needed for faculty running these kinds of endeavors, because they are a next level kind of work, above and beyond what a professor does on a daily basis.”

But once faculty members have the CCN’s support and curricular guidance to get the program off the ground, many physical resources are already available to program leaders through their university.

“We have journalists in training, we have the equipment, we have the infrastructure,” Finneman said. “So it’s simply a matter of applying it outside of the campus grounds, putting it into practice in the real world and making a difference.”

Charlotte Oliver (right) works with a fellow student journalist as part of UVM's Center for Community News.

Anna Watts

Nick Mathews, an assistant professor of journalism studies at the University of Missouri and coauthor of Reviving Rural News, believes that Vermont is inspiring new conversations and creative solutions to journalism challenges across the country.

“These are state institutions, right? Our job is essentially to continue to make our state better in any way that we can. And that’s what these organizations are doing,” Mathews said. But he also noted that small liberal arts institutions can play a role as well. “There are private institutions in small towns that have, frankly, no reporters, but they have a lot of passion. There is an enthusiasm here from people who see the need.”

Oliver, now a rising senior at the University of Vermont, hopes to carry her enthusiasm for local journalism into a career long after she leaves the Center for Community News. But she also recognizes the challenges that lie ahead for local news organizations and their employees.

“I would love to work as a journalist after graduating because I’m still learning so much from it, and it’s a really rewarding thing to pursue,” she said. But at the same time, “I hear a lot of qualms about having a really hard time making enough money to earn a decent salary, and that’s really a shame. Culturally, we uphold journalism as something that’s pretty important in principle, but we don’t really follow through.”

Regardless of whether students pursue journalism careers, Watts, the center’s director, believes its work will always have value.

“We’re about educating students who will go on to be more active and engaged citizens in the world,” he said. “They may not be journalists, but the skills, the networks and the understanding of how the government works are going to be valuable to them with whatever they do.”