You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

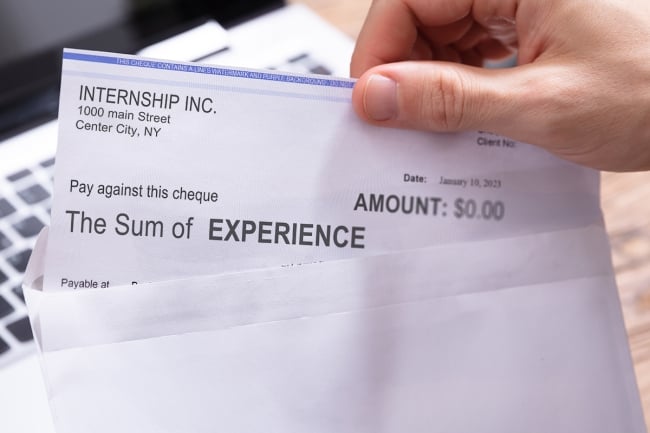

Unpaid internships used to be seen as an opportunity for students to easily get experience and credit, but data show those who complete paid internships have better outcomes.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

Unpaid internships have long faced scrutiny for their inaccessibility, especially for lower-income students who can’t afford to work for free. Now the National Association of Colleges and Employers is taking a firm stance against unpaid internships, arguing in a new campaign—called Unpaid Is Unfair—that such internships should be outlawed nationally.

“Congress should pass legislation requiring internships to be paid,” the organization wrote in a position statement released Tuesday. “For decades, interns have occupied a nebulous space in the employment world—sometimes being considered unpaid trainees and sometimes being considered fully paid employees. Modern legislation is needed to resolve this inconsistency.”

Shawn VanDerziel, NACE’s president and CEO, said the campaign is the crystallization of something that NACE has observed in its data: unpaid internships are not only challenging to access but also lead to less favorable employment outcomes for graduates.

“We’ve long recognized that unpaid internships are not providing outcomes that provide for equitable endings,” he said. “We’re on a mission to be proactive and to help people think differently than the old systems and ways that things have been done.”

Unpaid internships seen as beneficial because they offer students the opportunity to gain training, experience and, in many cases, course credit while providing employers with free or cheap labor. But NACE data show that while internships are an asset to employers and students alike, paid internships correlate with larger salaries and a higher number of job offers for students after graduation than unpaid ones. A 2022 survey found that students who had completed a paid internship received, on average, 1.61 job offers after graduating, while unpaid interns averaged 0.94. Paid interns reported making a median starting salary of $62,500, while unpaid interns earn a median starting salary of $42,500.

Some students cannot commit their time to a position that does not pay. Those whose parents don’t help them pay for their education often need to work during college to afford tuition, leaving little extra time for an unpaid internship.

That can have a negative impact on job prospects; according to the 2022 survey, students who had an internship—whether paid or unpaid—received more job offers than those who didn’t.

Currently, there is little regulation of unpaid internships. A handful of states afford unpaid interns the same rights against harassment and discrimination as paid employees. And on a federal level, a list of seven rules guides the lawful implementation of unpaid internships, including one requiring employers not to derive any “immediate advantage from the activities of the intern.”

Experience Versus Pay

While Tuesday’s announcement marks the beginning of what appears to be the first major campaign to end unpaid internships nationwide, students have been pushing for similar reforms for years.

Newspapers—both student and professionally run—across the country seem to run articles and op-eds every year questioning the morality and effectiveness of such internships.

“This phenomenon of unpaid internships reminds me of the idea that experience trumps pay, meaning that whatever money you’re not making will be supplemented by the experience you get from the internship,” Zavia Pittman, a student at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, wrote in the student newspaper, The Carolinian, earlier this year. “In some regards that may be true, but for the general public, compensation is just as important if not essential. Yes, you can build connections with people at the business you intern for, and maybe that will lead to other opportunities, but that is in the future. ‘Future opportunities’ don’t pay current expenses, and sometimes it’s hard to absorb said experiences when you’re stressing about rent.”

The advocacy group Pay Your Interns—which echoes Pittman’s argument with the tagline “Experience doesn’t pay the bills”—has worked for nearly seven years to end unpaid internships. The organization focuses on the federal government, on the theory that as the nation’s largest employer, it can serve as a model to others, said Carlos Mark Vera, the organization’s founder.

The group has had some success, pushing Congress to create a funding pool for its interns and, later, playing a role in the Biden-Harris administration’s move to pay White House interns.

“Life is about sacrifices,” Vera said. “But no one should have to go hungry to do an opportunity that’s basically required to get your foot in the door” in your chosen industry.

Vera agreed with NACE that all internships should be paid—and, based on the success his organization has had pushing for change in Washington, he believes it’s possible.

“When I started this work, people thought, ‘Well, it sounds nice, but it’s not going anywhere.’ [But] we changed the culture in D.C.,” he said.

Universities themselves have advocated in support of paid internships, with many providing stipends to support students in unpaid roles. Some have even refused to post unpaid internships on their campus job boards. VanDerziel said NACE’s members, composed of both career center professionals and employers, have reacted enthusiastically to the campaign.

“Our members are really concerned about equitable outcomes for their students,” he said.

At the same time, some colleges impede the movement by, for example, not allowing students to gain course credit for an internship they’re also being paid for.

Not everyone believes it’s necessary, or even advisable, to get rid of unpaid internships, however. Bryan Caplan, a libertarian economist at George Mason University, argues that students should be willing to exchange labor for training, just as they exchange money for a postsecondary education.

“There is really a strong reason to allow unpaid internships, which is that it is a way for someone who doesn’t really know how to do much of a job and isn’t really very useful to persuade someone they’re worth giving some training to,” he said.

He acknowledged that students are sometimes put in the difficult position of having to work to support themselves while taking classes but argued that doing so shouldn’t get in the way of an excellent opportunity. He suggested that students could even borrow money to support themselves while participating in a worthwhile unpaid internship.

“I’d say, ‘How good is this internship, exactly? What happens to people who do it?’ Maybe it is worth going and betting on yourself in that way,” he said. “Getting rid of unpaid internships doesn’t mean that people get great [paid] internships; a likely scenario is a lot of people just don’t get them at all.”

Advocates of paid internships counter that some of the positions that may disappear if unpaid internships are outlawed are the same ones that exploit students and provide no real benefit in the first place.

What Comes Next

The road to eliminating unpaid internships will not likely be a short one; NACE reported that 47 percent of internships in 2022 were unpaid.

VanDerziel said one of the first steps is simply changing attitudes about unpaid internships, which many people see more as a rite of passage or an obligation rather than a factor that can make a genuine impact on a student’s life after graduation. On top of the campaign launch—which features a series of videos in which a student who “just finished an unpaid internship” tries to pay her bills with commemorative mugs, high fives and references—NACE has also been sharing data with legislators in recent months, trying to show the correlation between paid internships and student success.

“We all have to start somewhere in thinking differently about the experiences that students are participating in. There was a time and a place for unpaid internships, but times have changed,” VanDerziel said. “Our campaign is a way to start the conversation, because it will take time and it will take rethinking of programs that are in existence to make them paid.”