You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

An employee at Polk State College in Florida went undercover to find out if contract cheaters could infiltrate increasingly popular remote proctoring software.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | RDNE Stock project/Pexels | Getty Images

Katie Ragsdale sat in an empty conference room on the campus of Polk State College in central Florida earlier this year and watched her laptop screen as a professional cheater she hired took an online multiple-choice College Algebra exam for her. She tried to act natural, knowing that any suspicious activity, such as prolonged glances away from the screen, could trip up Honorlock, an AI-powered proctoring service the college uses.

“I just sat there and pretended to take the test,” she said. “They were controlling my computer.”

Before the test, the hired cheaters had her download a VPN to hide their location outside the U.S. and the remote-control platform that provided the access for them to take over her laptop. On the day of the test, all Ragsdale had to focus on was proving her identity to Honorlock before the cheater took over her computer screen.

She turned on her computer’s camera, showed her student ID and scanned the room to verify there weren’t any obvious cheating tools at hand. Honorlock let her—and unwittingly her hired help—start the exam.

A screenshot of Ragsdale presenting her student ID during the Honorlock verification process.

Katie Ragsdale

Ragsdale got an A, the grade she paid Exam Rabbit, a contract cheating company based in Pakistan, $250 to achieve.

While the exam was a real assessment, Ragsdale wasn’t a real student.

Hiring Exam Rabbit was part of a sting operation crafted by Ragsdale, an instructional designer at Polk State, and her colleague Kimberly Hess, a math professor. They were carrying out an experiment to test whether students or contract cheating companies could infiltrate remote proctoring software, which has surged in popularity since the pandemic.

Blackmail Attempt

Although the experiment proved that Exam Rabbit was able to help Ragsdale cheat on her personal computer, it also proved that the college’s firewall blocks remote cheaters from using Polk State’s networks or campus computers.

In running the experiment, however, Hess and Ragsdale uncovered a new risk that students expose themselves to when using contract cheating companies: Blackmail.

Restrictions on the college’s credit card Ragsdale attempted to use (with their permission) to pay Exam Rabbit meant the payment didn’t process immediately. That’s when the threats of blackmail started.

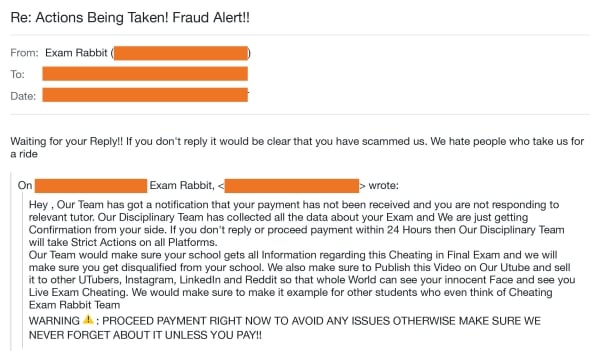

“Our Team would make sure your school gets all Information regarding this Cheating in Final Exam and we will make sure you get disqualified from your school,” said one email from Exam Rabbit to Ragsdale, which also threatened to publish her cheating video on YouTube, LinkedIn, Reddit and Instagram. “We would make sure to make it [ sic ] example for other student [ sic ] who even think of Cheating.”

One of the threatening messages Exam Rabbit sent Ragsdale after her payment for their contract cheating services didn’t process immediately.

Katie Ragsdale

The rise in online learning since the pandemic has afforded many students a newfound flexibility to balance academic demands with work and family responsibilities.

But for some students, the increased institutional reliance on third-party proctoring services to deliver exams remotely has also presented a new, high-tech opportunity to cheat. Numerous contract cheating services advertised online promise the ability to bypass proctor software, take control of a paying tester’s computer and complete the exam for them—presumably with an impressive score and without detection.

A study by online proctoring platform ProctorU showed that incidences of misconduct during remote test-taking in 2021 had nearly doubled since 2020; It was 14 times more common than it was in 2019. And while some professors have fewer concerns about academic integrity in online testing than they did at the start of the pandemic, 77 percent still believed that students were more likely to cheat online than in person according to a 2021 Wiley survey.

“Causing a Panic”

The concern that students—or their accomplices—could infiltrate remote-proctoring software was shared by some faculty members at Polk State, where more than 50 percent of courses are fully online (up about 20 percentage points since 2019) and 75 percent of students now take at least one class online.

“It was kind of causing a panic for other faculty,” said J. Cody Moyer, director of learning, technology and online education at Polk State, who asked the college’s provost for permission to conduct the experiment to test the validity of faculty fears. “We wanted to ease the nerves of faculty by finding out what is and isn’t happening, what’s possible and how these things work so that we understand as an institution how we can combat this even outside of proctoring tools.”

That premise guided the undercover investigation by Ragsdale and Hess. The resulting report, “Unmasking Academic Deception: A Student’s Eye View into the Shadows of Contract Cheating,” determined that while contract cheaters may help a student pass an exam under certain circumstances, paying a third-party to impersonate a student taking an exam comes with risk that could extend beyond a summons to the dean’s office.

“I knew blackmail was a possibility,” said Ragsdale, who added that students who use Exam Rabbit are also exposing themselves to potential theft of sensitive personal information. “They have screenshots of me taking this test and cheating.”

Even though she’d been communicating with Exam Rabbit anonymously, the cheater saw her name on the student ID she had to present during Honorlock’s verification process.

“The cheater was watching that the entire time,” Ragsdale said. “That’s how they were able to get my name.”

It didn’t take long for Exam Rabbit to start threatening Ragsdale after the brief lapse in processing her payment. The company began sending her and her friends a barrage of messages threatening “to burn her career.”

A screenshot of a contract cheater from Exam Rabbit posting threats of blackmail on Ragsdale’s friend’s Facebook page.

Katie Ragsdale

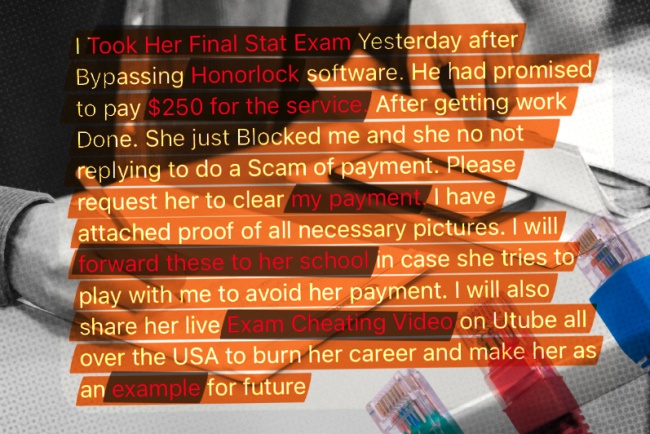

Although Ragsdale has strong privacy settings on her personal Facebook that prevent people she doesn’t know from posting on her page, the contract cheater started posting messages on her friends’ pages alongside pictures of her cheating on the exam. They threatened to send them to Polk State “in case she tries to play with me to avoid her payment.”

“I Took Her Final Exam Yesterday after Bypassing Honorlock software. He [ sic ] had promised to pay $250 for the service,” a Facebook account with the name Abdul Manan wrote. “She just blocked me and she no not replying to do a scam of payment. Please request her to clear my payment.”

The college then paid Exam Rabbit through an international wire transfer, which was accepted, and the threats stopped.

“To this day, nothing is stopping them from attempting to further threaten me for more money —they have reasonable proof of me cheating and can strike any time they choose,” she wrote in the report about her undercover operation. “This leaves me very unsettled.”

Exam Rabbit posted pictures on Ragsdale’s friend’s Facebook page that showed Ragsdale cheating on her exam. They threatened to expose her to her college and the wider internet if she didn’t pay for the cheating services.

Katie Ragsdale

When confronted with questions about Ragsdale’s experience, an unidentified member of the Exam Rabbit team responded with an emailed statement.

“We fully condemn any attempts to misuse the name of Exam Rabbit for illicit activities such as cheating or blackmailing,” the statement said. “Rest assured, we are committed to upholding the integrity of our services and maintaining the trust of our clients.”

An Honorlock representative said in a written statement that the company applauds efforts by Polk State and other higher ed institutions "to maintain the integrity of their exams, professors and university experience."

"All proctoring platforms are aware that for-hire cheating services can be used to take a student exam in the method used in this experiment," the statement said. "As proctoring technology evolves, we work to address the various ways that students and third-party cheating services can take advantage of the technology.

"....... Honorlock’s combination of AI monitoring combined with human review of video offers the best example of using multiple checks to determine if student actions during a test indicate cheating or are simply normal human behavior. We appreciate examples of circumventing the ethical testing process as it helps us prioritize research and development to determine if those pathways can be closed."

(This article was updated with the statement from Honorlock, which initially did not respond to requests for comment.)

“Very Suspicious”

Exam Rabbit’s website explicitly advertises the ability to cheat Honorlock and Proctorio, another third-party proctoring services, as well as the GED and two nursing-related standardized exams, TEAS and the HESI.

“When you look at the website of this particular service it’s very suspicious,” Ragsdale said. “There’s grammatical errors. The way you contact them is all through WhatsApp, which is end-to-end encrypted and a way to easily communicate with people outside the U.S. You also have to pay them through these unrecognizable platforms (that require banking information). And they don’t ask for the money upfront.”

Ragsdale, who still has an active Polk State student account created when she took a class there several years ago, didn’t raise any suspicions with Exam Rabbit about her true motives for hiring the service. Instead, Exam Rabbit told her exactly how to get away with cheating Honorlock, the remote proctor service Hess, the math professor, used to deliver exams to all of her students.

Just as it would for any student, the AI-powered proctor software recorded Ragsdale while she took the test. In addition to prolonged stares away from the computer monitor, Honorlock also reports such things as another person entering the room to the professor who can review the recordings.

“I did get a report that there was suspicious activity on Katie’s test, but it’s not what you’d think,” Hess said. “It was just because she was so bored while they took the test for her that she was looking around the room. They wanted me to review it in case she was talking to someone else in the room, which she wasn’t.”

Hess said that if she wouldn’t have been part of the contract-cheating experiment, she would have still reviewed the video of Ragsdale taking her test.

“One of the toughest things about being a professor is that we almost always cannot prove that our students are cheating,” she said. “If I were giving a test in a classroom and a student was acting suspicious I could intervene immediately. Whereas, in a remote setting where someone else is proctoring, we see it hours or days later. We just see the videotape and we can’t say, ‘Please show me what’s on your paper in front of you.’”

In addition to Exam Rabbit, Ragsdale also found a self-described tutor on Reddit who claimed they could bypass an exam delivered through ProctorU, another remote proctoring service. This time she paid the $180 fee before taking the test. But after three failed attempts at bypassing the proctor software—two on campus and one off-campus—Ragsdale asked for a refund which she never received.

It’s not clear how many students at Polk State or elsewhere have successfully employed contract cheaters to bypass proctor software.

“Do we think most of our students are going to Exam Rabbit and paying $250 for an exam? No. I don’t know that any of our students are doing that particular form of contract cheating” said Moyer, Polk State’s online learning director. “But are they sharing their login information with their cousin and their cousin’s taking it for them? It’s highly likely. That’s more of the game we’re in.”

A Shift in Pedagogy?

While Moyer hopes the results of the investigation demonstrate to faculty that the college’s networks and testing centers are at least protected from “the forces of evil,” the experiment has pushed Hess to consider how her own pedagogy could be one safeguard against emerging technologies used for cheating.

“We have to communicate to our students and let them know that not only is it bad to cheat on an exam, but there are other potential dangers as well,” Hess said. “As a professor, I have to change the way I assess my students. How can I phrase math questions in such a way that an AI bot can’t answer?”

Ragsdale added that it will take a coordinated effort among educators to ensure academic integrity in this new era of remote instruction. “We can’t use old solutions for new problems,” she said. “Education and technology [are] changing rapidly and our students are sharing new knowledge and strategies. We also have to do that as educators.”

Sara Rieder Bennett, president of the National College Testing Association, said use of remote proctoring software is likely here to stay.

“Once you’ve invested in that technology, and students are aware of the flexibility and accessibility that comes with those types of platforms, it’s hard to go back,” she said. “There are benefits many people have gotten out of these services.”

The fact that some students have also viewed it as a new opportunity to carry out the timeless temptation to cheat isn’t surprising.

“People cheat on everything,” said Bennett, who noted that opportunity is one of the biggest drivers of cheating. “So, it doesn’t necessarily matter the format we’re giving it in. What matters is how we’re asking students to approach and think about the material.”