You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Professor Sarah Brashears requires students to think creatively when designing their notebooks for her course, which in turn promotes attentive note-taking and intentional reading habits.

Sarah Brashears/University of Dayton

For the average professor, a student whose notebook is full of miscellaneous papers, magazine clippings, grocery lists, foil, dryer lint or playing cards doesn’t seem like an effective use of space. For Sarah Brashears, on the other hand, that student is more prepared to take notes for the week.

An art and design professor at the University of Dayton, Brashears asks students to create a bullet sketchbook, a creative process that inspires them to make collages using materials they collect—but also inspires more engaged note-taking as students think outside the box to synthesize information.

What’s the need: Getting students to read and process the information assigned to them in class is a growing challenge for a variety of reasons, but students often report lacking academic preparation skills, which includes note-taking.

The issue is not making content, lectures or professors more interesting to the students but instead helping students commit and connect to completing their chapter readings, Brashears says. “Students might sit down with the best intentions to read class materials. But 20 minutes later, they’re asking themselves: What did I just read?”

Prior research shows that people who doodle while listening to a lecture are more likely to have better recall, and the practice also provides reprieve from large amounts of information.

In the same vein, Brashears awards grades weekly for taking notes in the bullet sketchbook.

How it works: To create the sketchbooks, Brashears instructs students to purchase an unlined notebook (grids or bullets are fine), then get a trash bag and fill it with miscellaneous textured stuff. Materials could include old doodles, leaves, grocery receipts, yarn, ticket stubs, cat hair, ribbons, bar coasters, newspaper, used coffee filters, stamps, game pieces or maps—really, anything that will fit in a journal.

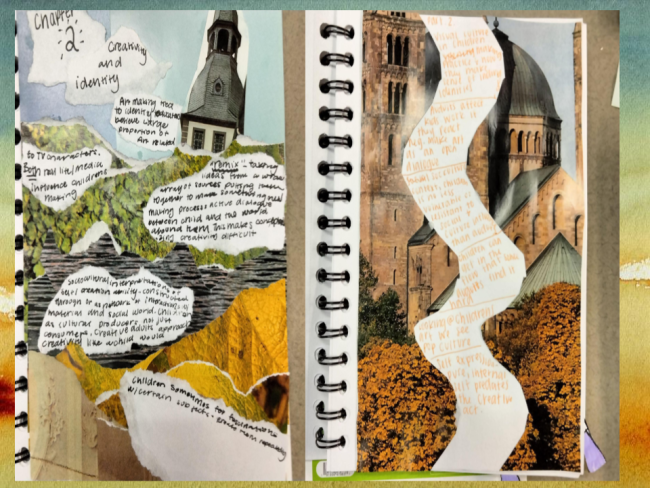

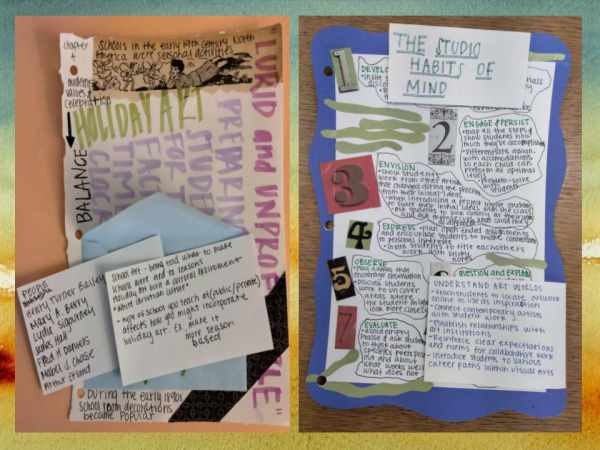

Two pages of student notes that use layering of images, text and other clippings to showcase important names and themes from the course content. Students are encouraged to use sticky notes or envelopes to add additional insights to their notes during class.

Sarah Brashears/University of Dayton

Students then layer the items in their notebook, gluing their treasures to the pages, making sure to leave spaces for note-taking or adding sticky notes to write on top of the layers.

Each week, students take notes for class in their creative sketchbook, concentrating on important facts, details, names and events. The notes are written on top of, next to, around and throughout their textured pages.

Brashears has students create their first few pages in class as a group, collaging together from shared materials for the first chapter and getting to know their peers. Then, students can split off and work independently.

Each student commits to taking notes this way for at least three weeks, and then after that they can take notes however they’d like to, but only one student in 10 semesters has ever opted out, Brashears says.

The impact: Brashears has found the project successful, because having visually interesting pages makes students more likely to be intentional in their note-taking.

“If they have spent time collecting materials and saving them, or watercoloring backgrounds, or dividing pages into boxes—whatever their choice of style—they are more likely to pay attention to the words they are writing down from the chapter,” Brashears explains. “They take a mental photo of that page and those words. They enjoy them.”

Within their notebooks, students are also more likely to draw or make their notes themselves visual. If a peer makes an interesting point during class, students often add a sticky note with more notes to their pages, making the books even more textured.

The assignment has resulted in students being more attentive to the reading material and completing it more regularly. Classroom engagement has also risen, with students more likely to ask and answer questions and give feedback. In addition, students share their notes with their classmates, looking at each other’s sketchbooks during class and sharing their processes for each page, creating a collaborative atmosphere.

Do you have an academic intervention that might help others improve student success? Tell us about it.