You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When the Department of Education first delayed the launch of the new Free Application for Federal Student Aid last March, officials projected calm and confidence.

The department assured students and institutions that the new form would make applying for aid easier, and the new formulas they were implementing would mean more federal money for low-income families. The “Better FAFSA,” as they took to calling it, would be worth the wait and ready when it launched.

Nearly a year later, the application is finally available to most students after a soft launch in late December that was riddled with technical issues, many of which remain unresolved. The department has yet to begin processing completed applications, preventing colleges and universities from sending aid packages to students. Lawmakers have called for hearings on the bungled process, and two investigations are underway.

Institutions are doing all they can while they wait, gearing up to process applications and get aid letters to students as quickly as possible. The stakes are high: without those letters, families are in the dark about their options to pay for college, and college-access advocates worry the challenges will discourage low-income and first-generation students from pursuing higher education entirely.

So how did a bipartisan effort to overhaul an outdated federal aid system become a political and logistical fiasco for the already-embattled Education Department?

The department has repeatedly blamed Congress, which refused requests for additional resources. Meanwhile, congressional Republicans have accused the department of being too focused on student debt relief—a key policy goal of the Biden administration—to commit fully to the FAFSA overhaul.

An Inside Higher Ed review of public documents and interviews with more than half a dozen Washington insiders familiar with the inner workings of the project suggest the truth is somewhere in the middle. Issues with the new FAFSA, from timing concerns to technical flaws, flew under the radar until the rollout became a full-blown crisis.

From the beginning, the massive project was overshadowed by the Education Department’s other priorities, including reopening schools closed during the pandemic. With the FAFSA overhaul progressing slowly, advocates began to worry that the department wouldn’t release the new form in time—concerns that proved prescient. Issues flagged repeatedly and publicly since last spring remained mostly unaddressed, while Congress, which ordered the changes, largely sat on the sidelines.

Mark Kantrowitz, a financial aid expert and consultant, said there is more than enough blame to go around.

“There were signs all along the way that there were going to be major challenges,” he said. “These congressional estimates of when something will or should get done are rarely accurate. But instead of being clear-eyed about it, the department basically pushed it off. Now they’re trying to build the plane while it’s in the air.”

An Education Department spokesperson said in response to a list of questions that the new form is the most significant overhaul of the application since its creation.

“The redesign includes overhauling over 20 systems, some of which have not been updated in nearly 50 years,” the spokesperson said, noting that the department’s efforts to develop and implement the new form received limited funding from Congress.

The spokesperson also noted that department staff members, along with key contractors and an information technology team from the president’s office, “have been working tirelessly to support this critical project.”

‘It Became a Crisis’

The FAFSA overhaul began in December 2020, in the final days of the Trump administration, when Congress passed the FAFSA Simplification Act as part of the end-of-year budget.

The legislation reduced the number of questions on the form from 100 to fewer than 40 and changed the underlying formula that determines students’ aid eligibility. The new law also significantly expanded Pell Grant eligibility and lifted a 26-year ban on Pell for incarcerated students, along with a number of other changes aimed at making aid easier to access.

President Biden’s incoming Education Department would have until October 2022 to get it all done.

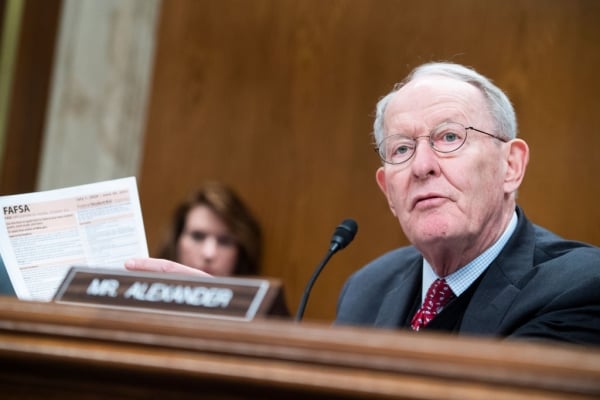

Simplifying the FAFSA was a top priority for former Tennessee senator Lamar Alexander, a Republican. Ushering the FAFSA Simplification Act through Congress was one of his last acts in office before he retired at the end of 2020.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

By the time Education Secretary Miguel Cardona was confirmed in March 2021, it was already clear to department officials that the task would require more time. That June, they were granted an extra year, pushing the deadline to Jan. 1, 2024, though they did opt to implement some provisions early—such as Pell for incarcerated students.

From the start, the department faced other pressing matters and political priorities. After Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act in March 2021, the department was tasked with distributing COVID relief funds to K-12 districts, nonprofits and higher ed institutions. And student debt relief, a marquee plank of Biden’s presidential platform, drew much of the department’s focus as officials took on the arduous task of fixing and streamlining the dysfunctional student loan system.

A source familiar with the project said they thought the department underestimated the work involved in the FAFSA overhaul from the get-go and viewed the project primarily as a system issue—one that wasn’t as high-profile as their other ambitious plans. Besides, there always seemed to be something more urgent, or more politically salient, that required attention.

“Simplification wasn’t anything anyone outside of the small bubble of people who care about this in D.C. was thinking about over the past three years until it became a crisis,” the source said.

The department spokesperson said that since Congress passed the FAFSA Simplification Act in 2020 and the FUTURE Act in 2019, which required the agency to make updates to the financial aid application, the Office of Federal Student Aid “has prioritized the overhaul of the FAFSA form and has been moving full speed to implement the law to make this experience far better for those completing the FAFSA.”

‘Refusing to Pay’

As the scale of the FAFSA fiasco became clear, Republicans were quick to point the finger at the Biden administration. They sent letters and held press conferences, lambasting the department for incompetence and rejecting claims that Federal Student Aid was deprived of the resources it needed to finish the more than $336 million project.

“This is not a funding issue. This is a management one,” North Carolina representative Virginia Foxx, the Republican chairwoman of the House Education and Workforce Committee, wrote in a letter to the editor of The New York Times.

Jared Bass, senior vice president for education at the left-leaning think tank the Center for American Progress, countered that Congress deserves the blame for setting an unrealistic deadline and then withholding funds, effectively kneecapping the department’s efforts before they got off the ground.

“They ordered this meal,” he said. “Now they’re refusing to pay the bill.”

Furthermore, Congress didn’t follow up publicly to make sure the department was on track to implement the law. When three officials responsible for FAFSA went to Capitol Hill last spring for hearings, they faced few questions about the project—even though the department had recently announced it wouldn’t launch the new form by Oct. 1.

What Is the Office of Federal Student Aid?

A performance-based organization, created in 1998, that manages the federal student aid programs for the Education Department. The agency is managed by a chief operating officer who is appointed by and reports to the education secretary. Federal Student Aid doesn’t have a board of directors, as do other performance-based government organizations.

Meanwhile, Congress required the Education Department to restart collecting student loan payments by October 2023 and share data with the Internal Revenue Service to automatically add federal tax information to the FAFSA. The department is also in the middle of a years-long effort to modernize its loan-servicing system. All that work falls on one agency: the Office of Federal Student Aid, which didn’t receive additional funding last year.

Bass warned Congress in March 2023 of “dire consequences” if the agency was not adequately funded.

‘It Should Not Have Been Hard’

Early on, the department decided that the most efficient way to implement the new FAFSA was to replace the decades-old central processing system, which used an outdated coding language and ran on an IBM mainframe, with a cloud-based system that would also administer some student loan programs.

Kantrowitz, who worked on the last major changes to the FAFSA in 1996, said revamping the code system was destined to be a massive undertaking.

“The underlying infrastructure was written in COBOL,” he said. “I haven’t written code in COBOL in 40 years. That’s an ancient language, not a modern database.”

A source familiar with negotiations over the FAFSA Simplification Act said those technical upgrades weren’t necessary. To fulfill the legislative mandate, the department just had to update the formula that determines how much aid a student is eligible for and redesign the form to be shorter and easier to fill out.

“It should not have been hard,” he said, adding that the decision to streamline the underlying systems caused complications. “I don't necessarily fault them for doing all that. But I think the vision and preparation to make that happen wasn’t well thought out.”

Bryce McKibben, senior director of policy and advocacy at Temple University’s Hope Center, worked with Washington senator Patty Murray, a Democrat, to help shape the FAFSA Simplification Act. He said that at the time they didn’t anticipate the complete technical remodel that the department ended up pursuing.

“When we were negotiating the law, we did not know that the Department of Education would make that synonymous with overhauling all of its legacy systems,” he said.

When the department asked for the extension, lawmakers were skeptical because they wanted students to benefit as soon as possible, McKibben said. That’s when department officials explained they needed to update the processing system in order to implement the law.

Key Changes to New FAFSA

- Replaces the Expected Family Contribution with the Student Aid Index to determine how much money a student should get.

- Expands access to the Pell Grant and bases eligibility on household size and adjusted gross income.

- Ends the discount for families with more than one child in college.

- Students whose families have an adjusted gross income of less than $60,000 won’t have to answer detailed financial questions, making for an easier process.

Multiple factors likely played a role in the current mess, McKibben said. They include the Trump administration officials who initially weighed in on the feasibility of the legislation when it was first proposed and negotiated in late 2019 and early 2020, before the pandemic. The Biden administration also had the chance to review the bill and ask Congress to make technical fixes. But those reviews didn’t flag many of the problems that have since bogged down the FAFSA rollout.

Case in point: just last week, Congress changed the formula that determines students’ aid eligibility as part of legislation to fund the government for a few more weeks. The fix came after the Education Department announced a change to the formula earlier in the week to comply with the law, which would have resulted in more Pell-eligible students next academic year.

Jon Fansmith, senior vice president of government relations and national engagement at the American Council on Education, said the back-and-forth over the formula is emblematic of the new FAFSA’s struggles.

“There have been three years to look at the legislative text, and it hasn’t changed,” he said. “How are we only finding out at the end of February that the formula isn’t what they’ve been telling parents? … It doesn’t inspire any confidence that there’s a coherent plan that’s being followed.”

Fansmith said he’s held out hope that things would improve, but the problems keep accumulating as the rollout progresses, which raises questions about whether the department will, in fact, begin processing applications this month as planned.

“There’s no reason to be confident at this point,” he said.

‘A Drain on the System’

Many longtime federal education policy experts see merit in congressional Republicans’ claims that the department prioritized student debt relief to such an extent that it impeded work on the FAFSA.

In what some sources said was an early sign of the administration’s priorities, Biden appointed Rich Cordray—a former director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau with no experience in administering federal student aid—as head of Federal Student Aid in May 2021.

Another possible indicator was that the Education Department didn’t start holding press calls about the new FAFSA until 2024; by contrast, it held regular calls about student loan relief, often featuring high-ranking White House officials.

President Biden and Education Secretary Cardona are among the White House officials who have been involved in key student loan announcements, making clear their commitment to providing borrowers with as much debt relief as possible.

The White House had a chance in December 2022 to get more funding for the new FAFSA project: Republicans offered a 20 percent increase for Federal Student Aid but stipulated that the additional funds couldn’t be used for Biden’s debt-relief plan, which was eventually struck down by the Supreme Court last June. NPR reported that the White House rejected that deal, which left Federal Student Aid with no new money.

Education Department officials have said debt relief and other projects didn’t detract from the new FAFSA. A source familiar with the department’s processes said that’s just not possible.

“To do what they are doing is a drain on the system itself,” he said.

‘Utterly Predictable’ Problems

As the calendar inched closer to October 2022, a year out from the department’s presumed deadline, advocates and higher education groups started to worry about the pace of the overhaul.

The department had awarded the $121.7 million contract for the project to General Dynamics Information Technology in March 2022 but shared little else about its work to update the form and the underlying system.

Cordray did offer some public reassurance in September 2022.

“Delivering the new FAFSA form [is] something we’re pushing hard to do by next October,” he said at the National College Attainment Network’s annual conference.

Five months later, an FSA official refused to commit to an Oct. 1, 2023, launch—the first of several warning signs that the project was off the rails. The agency made the delay official a month later, saying only that the form would be ready in the fourth quarter of 2023. By law, it had to be out by Jan. 1, 2024, but sources familiar with the project said that behind the scenes, progress was lagging.

The department remained tight-lipped about FAFSA’s problems, even as advocates and stakeholders pushed for more information. One of the most glaring technical glitches with the new form blocked students whose parents don’t have a Social Security number from submitting an application—an issue that college access professionals asked about for months.

“It’s an utterly predictable problem that should’ve been caught months before the form went live,” said a source familiar with the project.

The lack of transparency also confounded colleges, which were left waiting anxiously for further instructions.

“[The department’s] communications were so vague that I think it paralyzed institutions,” said Brett Schraeder, managing director for financial aid at the education consulting firm EAB. “Had they been more realistic, it might have helped some colleges dial up their efforts earlier.”

‘It Didn’t Have to Be This Way’

The Education Department made Congress’s deadline with two days to spare. But the form’s Dec. 30 launch was rocky and frustrated students who often found the site unusable. It wasn’t until Jan. 8 that the FAFSA was available 24-7.

“They had it open for 30 minutes on Dec. 30 so they could slide in under the deadline, but I basically heard, and all signs supported this, that they put it out unfinished,” Kantrowitz said.

The department seemed to be making progress on addressing the technical issues throughout January, offering regular updates on the number of completed applications. But those news releases glossed over the fact that the department wasn’t processing applications or sending students’ information to colleges. (Processing typically happens within days of a student completing the FAFSA.)

Colleges were supposed to receive the application information at the end of January, but on Jan. 30, the department said it would not begin sending processed student aid information until mid-March. The delay, which disrupted admission timelines and exacerbated college-access challenges for low-income applicants, seemed like the last straw.

A growing public outcry prompted Cardona to get more involved. In early February, he made a series of appearances at admissions and financial aid professional organizations’ conferences in Washington, D.C., in an attempt to assuage concerns. The department also allocated $50 million to help institutions navigate the new form on truncated schedules and said it would send a corps of volunteer financial aid professionals to underresourced colleges.

The twists and turns over the last few months have sowed confusion for students, families and institutions. So far, just shy of five million students have submitted a FAFSA. That includes almost a quarter of high school seniors, which is 41.5 percent fewer than last academic year. Nearly 18 million students complete the form in a typical year.

“I think we’re very likely to see an overall decline in FAFSA submissions by the time this is over,” Kantrowitz said.

Concerns are also mounting about the department’s ability to process and send student aid data as fast as it has promised. And as problems with the form remain unresolved and confusion continues to swirl, faith in the Education Department is dwindling.

Schraeder said it’s a shame that what could have been an easy victory for the department—and an overwhelmingly positive change for most families, especially those of low-income and first-generation students—has been overshadowed by the many missteps that now define the new FAFSA’s rollout.

“For the most part, when they can complete the form, students are having a good experience with the new FAFSA, and I’ve talked to lots of financial aid [professionals] who say it’s much shorter, quicker, less confusing,” he said. “It didn’t have to be this way.”