You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

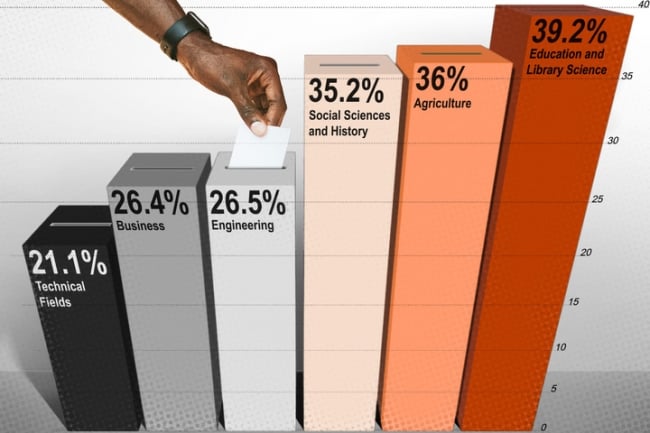

Engineering students voted at the third lowest rate of any field in the 2022 election, followed by business students and students in the trades.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Felix/rawpixel

For years, students studying science, technology, engineering or mathematics have voted at lower rates than their peers—especially lagging those in education and library science, who are most likely to vote.

In the 2022 midterm election, 31.3 percent of all college students voted—a decline of 8.7 percentage points from the previous midterm, according to the National Study of Learning, Voting and Engagement, which studies the voting habits of college students. But students in some disciplines voted at much lower rates; only 26.5 percent of engineering students voted, along with 26.4 percent of business students and 21.1 percent of students in technical and trade fields. Students in all STEM disciplines except agriculture voted at lower than average rates.

Experts believe that a key reason for the disparity is that STEM students don’t feel like the issues on the ballot relate to their interests or careers, which is an important factor in motivating students to vote.

They may also feel less informed about the issues of the day than their peers in the social sciences and humanities, who are more likely to learn about policy, social issues and current events as part of their courses.

“Sometimes [STEM students] don’t know how they feel about issues, or they don’t know where to go to find information that they trust,” said Bridget Trogden, dean for undergraduate education and academic student services at American University, who has spearheaded efforts to get voter education into STEM classrooms. “They feel it is more ethical for them to not vote than to go vote and make a choice they don’t actually agree with.”

Many STEM professors are trying to incorporate civic education into their classrooms, providing projects and lessons that center on political topics in order to pique students’ interest in the democratic process, she said. For example, an introductory biology professor might ask her students to conduct research on a candidate who holds a policy position on something they’ve learned about in class, a statistics professor could use gerrymandering data in a homework assignment or a civil engineering instructor could focus on local infrastructure projects or repairs, she suggested.

Fears of Partisanship

But roadblocks can prevent professors from implementing such lessons. Faculty members often feel these lessons don’t fit into the course’s learning outcomes, or that there’s not enough time to include voter education along with the regular curriculum, said Nancy Thomas, executive director of the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ Institute for Democracy and Higher Education.

And some worry about coming across as partisan—a view that is misguided, if not unfounded, Thomas said.

“There’s so much fear now. Somehow this message is landing that if you teach anything about voting, it’s somehow partisan, which is crazy. It’s not partisan,” she said. “You can help students learn about their responsibilities in democracy and it will affect both the Republican students and the Democrat students equally.”

There are also few resources available to STEM professors who want to incorporate civic education into the classroom. According to Trogden, the limited number of open-source assignments related to voter education for STEM students means that most professors must create their own assignments, which can be both time-consuming and challenging—especially if they are not experts in civic engagement.

Sanda Balaban, the executive director of Project Pericles, a consortium of higher education institutions focused on student civic engagement, noted that there’s a lack of funding available to colleges and universities that want to support and incentivize STEM professors to do this work.

“I think having more funders step up to the plate” could make a difference, she said. “There is a ripe audience who would be ready, willing and able, with some knowledge as well as resources, to be able to do that.”

But perhaps the biggest barrier to STEM professors incorporating civic education into the classroom is that few of them know it’s a problem.

“What I’ve found is most STEM faculty have no idea about this,” said Trogden. “When you tell them, they’re shocked. And then the next thing they ask is ‘What can we do about that?’”

Linking Science to Public Policy

Some student voting advocacy organizations have begun developing resources that can at least serve as a jumping-off point for professors seeking to incorporate civic education into their curricula.

The Students Learn Students Vote Coalition released a Science and Civics Guide, which gives professors language they can use to communicate to their students that their voices matter, and that science and public policy are closely linked.

“Elected officials make decisions about what issues receive funding, and how those funds are distributed for research and development,” reads one of the guide’s subsections. “This impacts countless scientific fields, from cybersecurity to marine biology to chemical engineering. It can also have devastating impacts on public health: for more than 20 years, Congress blocked funding for the Centers for Disease Control to study gun violence. Hundreds of thousands of lives were lost to gun violence during that time.”

The guide also notes the specific ramifications for STEM students. It points out that without federal funding, some professors have “moved on to other specialties, and some even discouraged their students from focusing on this topic because of the difficulty of procuring funding for this research.”

The coalition released a guide in 2022 called Your Major on the Ballot, which lists dozens of majors and five key political issues relevant to each one.

Emma Godel, who wrote the previous iteration of the guide when she was a student at American University, said in an email to Inside Higher Ed that her goal with the project was to “challenge the assumption that voting/other civic behavior is just an activity for political science/similar majors. All throughout my time in college and grad school, this was one of the most common reasons my peers cited for not voting and not being interested in politics in general—because it wasn’t in their textbooks [and] classrooms, it probably wouldn’t be in their lives.”

Providing students with information that proves that untrue, she said, can go a long way in turning disengaged students into impassioned voters.