You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

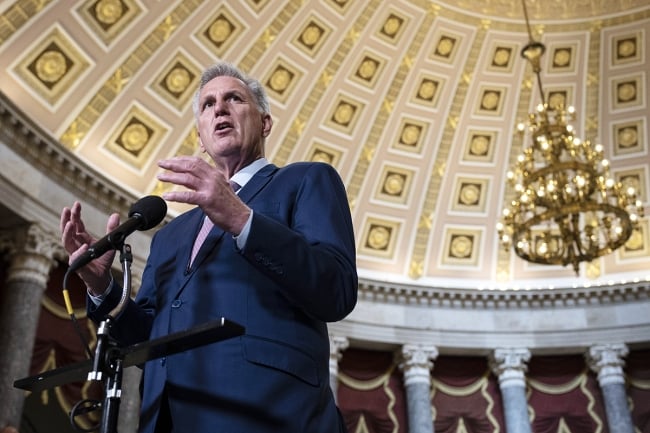

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy says he wants to avoid a government shutdown, but he’ll have to wrangle a fractured caucus and overcome a number of budget disagreements to make that happen.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

In more normal political times, higher education advocates, experts and lobbyists might be expecting to see progress on a number of issues once Congress returns from its August recess. They’d be optimistic, for starters, about the prospects for doubling the maximum Pell Grant award for students, expanding Pell to cover short-term programs like job training classes or standardizing federal financial aid applications.

Instead, all eyes will be focused on the fight over the federal budget and the question of whether Congress can keep the government open after the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30. Some House Republicans want steep cuts in spending and an impeachment inquiry into President Biden, and they’re vowing to force a shutdown if they don’t get them. Meanwhile, the Senate is gearing up to pass appropriations bills, along with a short-term funding measure designed to avert a shutdown.

Senators returned from recess this week, while the House will be back in session Tuesday.

Other policy issues will likely take a backseat to the budget battle.

“It’s a very challenging climate to say that anything of substance can be done until they have some clear path forward to resolve the funding issues,” said Jon Fansmith, senior vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education. “I don’t know if anyone looking at it right now feels optimistic that there’s much of a clear path forward at this point.”

Even when this Congress began its session in January, few expected it to be productive in terms of higher education policy, with Republicans holding a four-seat margin in the House and Democrats controlling the Senate and White House. Although higher education issues such as student loan reform have attracted increased attention in recent years, this policy area hasn’t historically been a top priority for leadership, which makes advancing legislation more difficult.

Several experts say that if Congress does move on a higher education issue, it will be a bill that would expand the Pell Grant to cover programs that run for fewer than 15 weeks. Supporters of this policy, commonly referred to as either short-term or workforce Pell, say it would help more students access job training programs. The Pell grant is geared toward low-income students. Both Democrats and Republicans have introduced bills that would make short-term Pell a reality.

“In terms of actual bipartisan legislation, short-term Pell remains the front-runner for something in the higher ed space where you could see action,” Fansmith said. “It wouldn’t be shocking to see something that’s proposed in the near future that gets bipartisan support.”

‘A Staggering Level of Disagreement’

Resolving the budget impasse will mean bridging large divides between the House and Senate over how much to spend and what to cut. For higher education, there’s a lot riding on what transpires. The two chambers are currently at least $12 billion apart on the Education Department’s budget, and they’re billions farther apart on the entire federal budget.

“It’s a staggering level of disagreement that doesn’t lend itself to any sort of easy resolution,” Fansmith said.

House Republicans have proposed defunding Federal Work-Study, which provides part-time jobs for undergraduate and graduate students who have financial needs, and cutting $759 million from the higher education section of the Education Department’s budget. The higher education section includes funding to support historically Black colleges and universities, campus childcare, and college preparatory services for underserved student groups, among other programs.

The Senate plan would trim about $10 million from Federal Work-Study’s $1.2 billion budget and cut $265.6 million from the higher education section. Most of the higher education cuts would come from the pot of money designated for earmarks. Colleges and universities have been a top beneficiary of earmarks in previous budgets, so the cut would mean that fewer projects are funded.

The Senate is planning to boost the maximum Pell Grant award from $7,395 to $7,645 for the 2024–25 academic year, while the House’s plan would keep the maximum award at $7,395.

Jared Bass, senior vice president of education at the left-leaning think tank the Center for American Progress, noted that the House Appropriations Committee hasn’t released more details yet about what’s specifically funded in the department’s budget beyond the top-line numbers. Those details are expected when the committee takes up the budget bill that includes the Education Department.

“What we did see is there were a lot of drastic cuts proposed for higher education and education writ large,” Bass said. “So funding is a major concern for Congress and for anyone who’s paying attention to higher education or education right now.”

If Congress can’t pass a budget or a continuing resolution to avert a shutdown by the end of the month, it will create some additional challenges for colleges and universities.

“It means pain and difficulty, depending on the length of the shutdown,” said Craig Lindwarm, vice president of governmental affairs at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities. “Contacts at research agencies critical to the advancement and continuation of vital research will go dark. The progress in putting out funding opportunities and collaboration with researchers can grind to a halt.”

A shutdown this fall also could further complicate the rollout of the revamped federal financial aid application known as the FAFSA, which serves as the gateway to all federal financial aid, in addition to a broader overhaul of the system that determines how much aid a student should get. The overhaul is aimed at making it simpler to apply for aid. The revised application, which is already delayed, is set to launch in December.

“If you suddenly start having a lot of federal staff unable to work in October and November, what that might mean for those updates to the system that depends on those changes?” Fansmith asked. “That’s troublesome. That’s not good news.”

So far, the House appropriations committee has passed 10 of the 12 appropriations bills that comprise the federal budget, while its Senate counterpart passed all 12 on a bipartisan basis. After the committees approve a bill in each chamber, it heads to the floor for a vote. The Senate is planning to consider a package of three budget bills next week. Typically, when the House and Senate pass different versions of legislation, the two chambers negotiate over the differences in a conference committee.

“Congress has a lot of work left to do with the appropriations process, but at a minimum, it begins with keeping the government open,” Lindwarm said.

Few Glimmers of Hope

Beyond keeping the government open, Congress also needs to pass an updated Farm Bill, a wide-ranging package of legislation that sets the policy for agriculture, nutrition, conservation and forestry and includes millions for agriculture research at public land-grant universities.

Advocates see a chance in the Farm Bill to improve college students’ access to the federal food-assistance program known as SNAP and to address the historic underfunding of historically Black land-grant universities. Programs authorized by the Farm Bill start to expire Sept. 30, but lawmakers aren’t expected to meet that deadline—a short-term extension appears likely.

David Baime, senior vice president for government relations at the American Association of Community Colleges, said his group is focused on the Farm Bill, the appropriations process, making the Pell Grant tax-free and short-term Pell.

“We are optimistic,” he said of the chance to expand the Pell Grant to short-term programs. “Staff are deeply engaged in working out the specifics on behalf of the members.”

Before the August recess, the Senate education committee was supposed to consider legislation related to short-term Pell, but that hearing was canceled. Passing it is a priority for the House education committee and other key lawmakers. Negotiations in the past have broken down over whether to include for-profit and online programs— something that Senate Democrats have historically opposed—and it’s unclear if lawmakers have resolved their differences on those issues.

And then there’s the long-awaited reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, which was last updated in 2008. The law is supposed to be renewed every five years. Reauthorizing the act is a top priority for Representative Virginia Foxx, the North Carolina Republican who chairs the House education committee. She and others have tried without success over the years to pass comprehensive higher education legislation.

Foxx’s previous attempt included limits on how much students can borrow, new ways to hold institutions accountable and less regulation of for-profit colleges. Democrats’ attempts at reauthorization have proposed making community college free and implementing stricter accountability measures for colleges. Republicans would likely use this next attempt to pass measures aimed at free speech on college campuses, to overhaul or end graduate student loans, and to create new accountability measures for all institutions.

Baime and others are expecting to see a bill, or multiple bills related to higher ed reform, from Foxx. Even if those proposals don’t move forward, the hearings, markups and debates will indicate where Republicans and Democrats might find some consensus down the road.

“Sometimes there’s an opportunity when legislation isn’t moving to really advance the discussion,” Fansmith said, “because you have, in some cases, the breathing space to put different proposals out there and work on them.”