You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

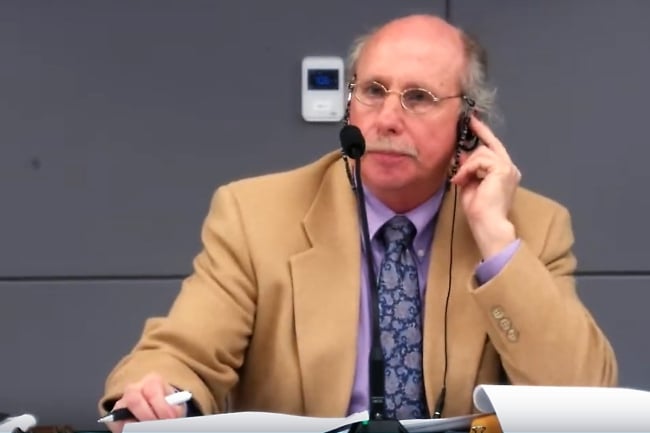

Andy Everman, the chair of the Mott Community College Board of Trustees, and a group of fellow trustees are facing criticism for a new interim president hire.

Mott Community College

The Board of Trustees at Mott Community College recently caused an uproar among faculty, staff and community members when they voted to hire an interim president without higher ed experience.

Critics see the move as the last straw in a series of questionable decisions since the board of the college in Flint, Mich., partly changed over in January 2023. They say trustees have been mired in drama and infighting for over a year, regularly holding fractious, multihour board meetings. Some employees worry the dysfunction could put the college’s accreditation at risk.

Last week the board voted 5 to 2 to offer a six-month interim presidency to Shaunda Richardson-Snell, who started this week. She’s held executive positions at major companies, including General Motors and Delphi, and holds a master’s degree in business administration but has never worked for a college or university. Two of the three other candidates for the position have Ph.D.s, and all have experience working in academic settings—including the college’s vice president of student academic success, Jason Wilson, who is currently earning his education doctorate and was serving as interim president until Richardson-Snell took the job.

At last week’s meeting, Andy Everman, who became chair of the board last year, made a motion to enter into closed session to discuss offering Richardson-Snell a contract before hearing public comments, upending the published agenda. Trustees Michael Freeman and Art Reyes, who ultimately voted against Richardson-Snell’s contract, argued that members of the public should be allowed to speak before the decision; they were outvoted. (Everman did not respond to requests for comment.)

After the board announced Richardson-Snell’s selection, their attorney further inflamed tensions by reading some of the benefits Richardson-Snell would receive, including an annual salary of $237,500, up to $15,000 for moving expenses and an $800 monthly “car allowance.”

The list of benefits worried onlookers. “If all of this is happening, this is not an interim—no way,” said Larry Juchartz, a professor of English who previously headed the faculty union for 12 years. “We anticipate that the next step will be for them to simply announce, ‘We’re making this interim a permanent position.’”

Dozens of people, including many residents of Flint and surrounding Genesee County, expressed outrage during a largely scathing public comment period, which lasted more than two hours.

“This lady has never been a teacher before, and y’all are paying her all this?” Arthur Woodson, a community member, said of Richardson-Snell. “Y’all are crooked … Y’all keep doing things like you don’t even care.”

An Unusual Process

Distressed employees say the hiring process for the interim president has been unorthodox, to say the least.

For one thing, board members typically hire an internal administrator as interim president while they search for a permanent leader. But when the previous president, Beverly Walker-Griffea, announced in May she would be leaving the college after 10 years, the board announced a search for an interim. (Walker-Griffea is now the inaugural director of the Michigan Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement and Potential.)

The board also listed a bachelor’s degree as the minimum degree requirement for the position, a decision some professors and administrators criticized. Everman argued at a May meeting that the lower educational standard is allowed by state law, though Walker-Griffea pushed back that requiring less than a master’s degree is highly unusual for a campus president job search.

Richardson-Snell has a master’s degree, but Kim Owens, president of the college’s faculty union, the Mott Community College Education Association, is skeptical about the process that led to her hire.

“Something is not adding up with their choice,” Owens said. “Her résumé looks great from a business perspective, but we are so much more than that.”

Now faculty members and administrators are fighting the decision—and general frustrations with the board—on multiple fronts.

Chris Engle, dean of counseling and student development and president of the college’s supervisors and management union, warned trustees at the meeting that the union would notify the college’s accreditor, the Higher Learning Commission, of their concerns about the hire.

Owens said the faculty union is ready to file a complaint with the HLC as well, noting it’s better for the college to be on the accreditor’s watch list now than lose accreditation down the line as a result of mismanagement. The union also filed a Freedom of Information Act request seeking materials related to the hiring process, including board members’ notes from the interviews. She noted that trustees didn’t use any kind of scoring rubric, another aspect of the process that raised eyebrows.

Patrick Hayes, an adjunct communications professor at the college, went so far as to file recall petitions against three board members in the aftermath of the meeting: board vice chair Janet Couch, trustee John H. Daly and board secretary Wendy Wolcott. (Everman and board treasurer Jeffrey Swanson also voted for Richardson-Snell but are up for re-election in November and can’t be recalled under Michigan state law.)

“It really all just struck me as lacking transparency and lacking accountability,” Hayes said of the hiring process. “I don’t expect that any elected official has to do what I want all the time as a voter, but I do expect that they are willing to listen to constituents and also explain why” they make the decisions they do.

Richardson-Snell, who grew up in Genesee County, told Inside Higher Ed she was eager “to return to home” and “contribute to the education and success of the next generation.”

She pushed back on the idea that her background isn’t right for the role.

There’s a “growing trend in higher education to pull leadership from a pool of industry experts and business executives [to] bring a fresh eye, a fresh perspective,” she said. She plans to focus on continuing to increase enrollment, retention and graduation rates and find “opportunities to diversify and increase revenue streams,” “develop new corporate partnerships” and focus on skilled trades and vocational programs.

“I have a tremendous amount to contribute to an already thriving institution,” she said. “Those who may not be yet supportive, they don’t know me … My unwavering focus is on the students, and I know that that’s a shared vision across the board here at Mott.”

While she’s not sure yet if she’ll apply for the permanent presidency, she believes she has “the qualifications to undertake the permanent position, as well.”

A History of Problems

Faculty, staff and community members see Richardson-Snell’s contract as the latest in a series of controversies involving the board.

Juchartz said that in the past, “We had a board that was so efficient, it was boring.” But for the last year and a half, that hasn’t been the case. He and others have harbored concerns about the tone of board debates, which have become lengthy and acrimonious.

Early signs of tumult started at a meeting in January 2023, when Freeman and former board chair Anne Figueroa accused Everman, Couch, Swanson and Wolcott of allegedly violating the open meetings act. Figueroa said she got the impression, based on a conversation with a former board attorney, that the group had discussed board business privately in advance of the meeting, including what board positions each would occupy. A tense discussion about board policy followed.

When Everman became chair, one of his first moves was to try to replace then board attorney Amberly Brennan, with little public explanation. His initial efforts didn’t garner enough votes, but in a letter read at a meeting in April, Brennan’s firm, Collins & Blaha, offered to step aside and allow the board to choose another firm. The board majority voted to do so, despite pushback from Reyes that there was no investigation into any complaints against Brennan. The board then operated without an attorney for months as members argued about who should replace her. In December 2023, they selected William Brickley, though his firm, Garan Lucow Miller, had no higher ed law experience. That decision also sparked controversy among faculty, staff and community members.

Bobbie Walton, a local activist who previously ran for the Michigan Senate, has spoken out at board meetings for months, repeatedly filing FOIA requests for information about board decision-making. She even sent a complaint to the state attorney general in January raising concerns about Brennan’s ouster and a lack of transparency. The octogenarian is the founder of a political action committee, BABs (Bad Ass Bitches) for Democracy, and plans to mobilize against the board members up for re-election.

“I feel like the skunk at a garden party,” Walton said of her attendance at board meetings, but she believes the community needs to hold the board accountable.

Paula Weston, an English professor, said in retrospect, the skirmishes in the recent past feel like warning signs. She worries there’s some form of “cultural warfare” going on, she said, though the board majority’s vision for the college remains unclear.

One administrator, who asked to remain anonymous, said they fear that what’s happening at Mott echoes the political infighting ravaging K-12 school boards over issues like diversity, equity and inclusion efforts— even though those topics have yet to come up in any substantial way during meetings. The administrator and others also noted parallels with North Idaho College, which earned a show-cause sanction and multiple warnings from its accreditor due to dysfunctional board governance.

Owens hopes none of the board strife trickles down to affect students, who are disproportionately people of color and from low-income backgrounds.

But it may be hard to avoid.

“You need someone steering the ship who knows where they’re going and what they’re doing, and we don’t have that right now,” she said.