You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

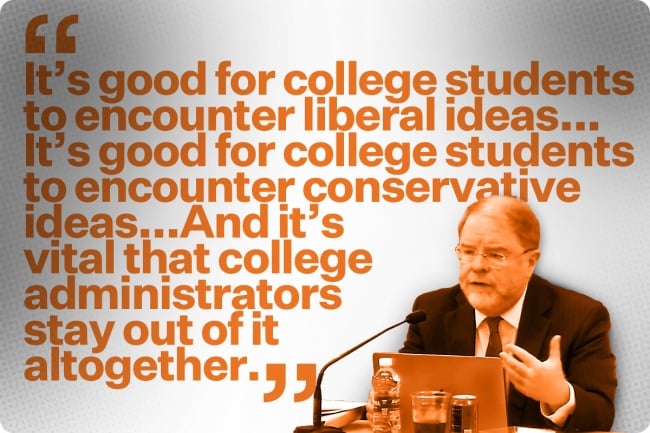

UNC System president Peter Hans has defended the board of governors’ DEI repeal vote as a measure of political neutrality.

Illustration by Justin Morrison for Inside Higher Ed | Screenshot from YouTube

The University of North Carolina system last month became the latest public university system to eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) offices and spending. It’s another victory for the national anti-DEI crusade that has become a defining higher ed issue in state politics.

But unlike in states such as Texas and Florida, where policymakers mandated DEI cuts by law, the decision in North Carolina was made by the university system’s governing board.

On May 23, the board voted 22 to 2 to repeal its DEI policy and replace it with one called “Equality Within the University of North Carolina,” which does not mention race at all and enshrines commitments to nondiscrimination, viewpoint equality and freedom of expression. It also includes a clause on “maintaining institutional neutrality,” which requires university employees—staff, not faculty—to refrain from voicing opinions on “social policy” or “political controversies of the day.” Campus leaders are required to report their compliance plans to system officials by Sept. 1.

After the vote, board member Pearl Burris-Floyd, a Black woman and former Republican state legislator, attempted to reassure constituents that the vote would not lead to the total elimination of services and support staff for minority students, and that the board has not “turned their backs on them.”

“Even if it’s not called DEI, we have a way to help people and make that path clearer for all people,” she said at the meeting.

She was trying to assuage concerns that the decision would lead to a cascade of layoffs and the shuttering of support resources for UNC’s students of color—understandable fears given the way DEI restructuring has played out in states where lawmakers are enforcing cuts. In Texas, state authorities balked at colleges’ initial strategies to meet a legislative anti-DEI mandate, forcing them to take more drastic measures or face legal and financial consequences. In Florida, the first state to pass an anti-DEI law, universities have been slashing diversity offices and administrative positions left and right.

Things could have gone the same way in North Carolina. The Carolina Journal and The Raleigh News & Observer both reported in March that state lawmakers were discussing the possibility of introducing an anti-DEI law this session similar to Texas’s. Wade Maki, a philosophy professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and chair of the system’s faculty assembly, said he supported the board’s DEI measure in part because he’d heard the system pushed to keep the decision in-house and out of lawmakers’ jurisdiction for enforcement.

“My understanding is that the board and the system leadership together managed to get the vote delayed in the Senate, so that we could look at doing something internally,” Maki told Inside Higher Ed in April, when the DEI repeal proposal first passed out of the university governance committee.

Now the campus community is waiting to see whether UNC’s gambit to maintain control will make any difference in the outcomes for students and staff. Maki believes it will.

“We all value controlling our own future,” he said. “This will help us ensure that we can keep what is important for our diverse students’ success while also addressing the concerns of our legislators and stakeholders.”

Others are skeptical, especially since the system’s board has weathered accusations of partisan overreach in recent years.

A system spokesperson told Inside Higher Ed that officials don’t yet have guidelines for how campuses can comply with the new policy but they should soon. Implementation is expected to begin in the fall.

Tai Stephen, an incoming freshman at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is worried about not only the repeal of DEI but also the message it sends to students of color on the system’s campuses.

“It makes me feel like UNC isn’t a place for people like me,” said Stephen, who is Black and identifies as queer. “It’s turned a very happy, exciting thing into something I’m nervous and kind of sad about.”

‘Institutional Neutrality’

UNC system leaders and governing board members are emphatic that the repeal and replacement of the DEI policy is not a political crusade. Art Pope, a board member and former Republican state legislator, said it’s a stopgap against political entanglement, and a cautionary measure to keep the system from running afoul of anti-discrimination laws.

“There is pending litigation which would not be appropriate for me to speak on over concerns at the campus level that some DEI program did discriminate based on an assignment to a class or identified group, rather than based on individuals,” he said. “This makes it very clear that there’s no conflict between our policies and the constitution.”

The UNC board’s policy vote differs in some significant ways from anti-DEI legislation passed in other states. For one, it has no bearing on classroom content, whereas “divisive concept” bans have been central to anti-DEI laws in Alabama and Florida. And it includes some measures to ease heightened political tensions over DEI funding: at the same meeting where the board repealed the DEI policy, system leaders said UNC Chapel Hill’s Board of Trustees did not have the authority to divert its $2.3 million DEI budget to fund police and campus safety, overturning a decision that Chapel Hill board chair Dave Boliek told Inside Higher Ed was a direct result of trustees’ displeasure with pro-Palestinian student protesters.

A UNC system spokesperson wrote that the goal of the new Equality Within the University policy “is not necessarily to cut jobs,” but to distance the university from “administrative activism” on hot-button social and political issues.

“It is going to take some time to determine how many positions could be modified or discontinued to ensure that institutions are aligning with the revised policy,” the spokesperson wrote. “Any savings would be directed to student success initiatives.”

Stephen worries that the redirection will dismantle spaces intended to give students like him a sense of belonging.

“Going to a predominantly white high school, myself and a lot of my peers who already struggled to find community were really looking forward to college, which promised to have those structures for us,” he said. “Now I don’t know if those will be around when I get there.”

UNC Chapel Hill has 35 staff members with roles related to DEI functions, whose salaries total upwards of $3 million, according to the conservative Martin Center for Academic Renewal. Only North Carolina State University has a comparable budget and staff for DEI—36 employees, earning about $3.3 million in salaries—but most campuses have fewer than 10 DEI staff.

Stephen, whose parents teach at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, said he fears a mass exodus of minority and speciality staff from UNC campuses.

“Growing up around UNC educators, I know people want to keep doing this good work. But this is going to make it hard for them,” he said. “How will those communities persist if there’s a mass exodus?”

Taking Back Control

Maki said the legislature’s decision to put DEI into the hands of the board of governors is indicative of a unique relationship in North Carolina between lawmakers and the university system, which he calls “the North Carolina way.”

“There’s just more trust between our legislature and our board, our board and our system office and our system office and the faculty,” he said.

In other states, a lack of trust between those parties has led to chaotic results. In Wisconsin, the Republican-led state house held up millions of dollars in funding for the state university system over disagreements on DEI spending, kicking off a war of attrition that lasted over six months and nearly derailed the University of Wisconsin system budget.

Paul Fulton, a former UNC system board member who served on the UNC board of governors with current system president Peter Hans, sees the board’s DEI vote as a sign that system leadership managed to talk legislators down from taking unilateral action on DEI themselves—no small feat, he added, for a higher ed leader in today’s political climate.

“If they leave it to the board of governors, then I think there is hope. They’re much more trustworthy than Republican lawmakers or those darn Chapel Hill trustees,” he said. “That’s the sort of stuff [Hans] deals with: How far do I need to go to keep the peace and still keep my job? It’s an impossible task, but he’s very savvy.”

Pope said he isn’t aware of any backroom negotiations that put the DEI policy in the hands of the system. But from his experience on both sides of system governance, issues of complicated administrative restructuring are best handled by the universities themselves.

“I have full confidence in the legislature, and they have full constitutional authority to have the last say in governance and spending here if they want,” he said. “But I think there’s agreement that it’s a better approach to delegate governance to those that are closer to the issues.”

He added that he’s sympathetic to the needs of a diverse range of students on UNC campuses, and that he wants to prevent the loss of effective student success resources as a result of the policy change. But he’s long been keen to trim what he sees as excessive funding for DEI, and to chastise campuses that he says have, over the past several years, “crossed a line” from inclusion to discrimination.

For students like Stephen, the damage is already done regardless of how the policy implementation plays out.

He hoped that college would provide an escape from the constant incursion of politics that shaped his high school education. After the North Carolina legislature passed a Parents Bill of Rights law last summer giving local school boards more control over K-12 schools, Stephens’s high school in Charlotte stopped allowing students to change their pronouns on school forms without parental permission and offered fewer lessons about slavery in America.

“I wasn't really that surprised to learn that now diversity as a whole is being attacked [at UNC],” he said. “But it's still very disheartening.”