You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Seton Hall University has denied swirling allegations of missteps on Title IX.

Joe829er/Creative Commons

After weeks of relative silence, Seton Hall University has provided a resounding defense of embattled president Joseph Reilly, who has been accused of overlooking allegations of sexual misconduct in his past role.

Specifically, Reilly was accused of failing to report instances of alleged sexual harassment when he was rector and dean of the university’s graduate seminary, a position he held from 2012 to 2022. He then went on sabbatical and returned in another role before being hired as president in 2024.

In a statement to Inside Higher Ed, Seton Hall provided a sweeping denial of those accusations, days after Politico published documents indicating that Reilly had failed to act.

Those documents, which Politico was the first to publish, consisted of letters addressed to Reilly during an inquiry launched into a sprawling sexual abuse scandal involving former cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who investigators determined “used his position of power as then–Archbishop of Newark”—which sponsors Seton Hall—“to sexually harass seminarians” for decades, according to a 2019 university report. McCarrick was later defrocked but avoided charges due to a dementia diagnosis.

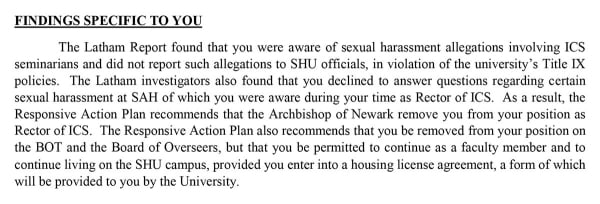

In two letters, one dated November 2019 and one February 2020, Joseph LaSala, who chaired a special task force on Seton Hall’s Board of Regents that looked into the abuse scandal, wrote to Reilly that an investigative report found he was “aware of sexual harassment allegations involving [graduate] seminarians and did not report such allegations to SHU officials, in violations of the university’s Title IX policies.”

LaSala added that a “responsive action plan” recommended that the Archbishop of Newark remove Reilly from his then-role as rector, as well as his position on the Board of Trustees—one of two governing boards at Seton Hall—though he would be permitted to keep his faculty job and live on campus.

Part of the 2019 letter from LaSala, which was shared with Inside Higher Ed by a source who asked to remain anonymous.

But Seton Hall official have disputed the contents of one of the letters, saying it was never sent.

“The February 18, 2020 letter implying disciplinary action against Monsignor Reilly was never sent and Monsignor never saw it until it was reported in the Politico story,” they wrote to Inside Higher Ed. “Further, the description of the Responsive Action Plan in the letter is inaccurate.”

The Seton Hall officials told Inside Higher Ed that, contrary to the letter Politico published, the Responsive Action Plan recommended that Reilly remain “on the Board of Trustees and the Board of Overseers” and “as an employee of the University.” It also determined that he would “be eligible for future employment.”

(Seton Hall did not address the veracity of the November 2019 letter, which also alleged that Reilly violated university Title IX policies and recommended his removal.)

“Soon after becoming Rector/Dean of the Seminary in 2012, a seminarian approached Monsignor Reilly and conveyed an incident in which he felt he had been the victim of inappropriate behavior by a fellow seminarian,” Seton Hall officials wrote in response to questions from Inside Higher Ed. “After consulting with seminary faculty, Monsignor Reilly investigated the incident and found the claim credible. Taking action, he dismissed the offending seminarian from the seminary soon after the complaint.”

The officials noted that Reilly “reported the incident and his disciplinary action within the Archdiocesan processes.” But they added that Reilly later realized—after receiving Title IX training—that “he should have also communicated the incident with the University’s Title IX office.”

A Mystery Report

Seton Hall has thus far declined to release the results of the investigation conducted by the law firm Latham & Watkins into McCarrick’s alleged abuse. Nor has the university shared details of the Responsive Action Plan, despite increasing pressure to do so—including from New Jersey’s Democratic governor, Phil Murphy, and others.

Inside Higher Ed has repeatedly asked to see the Latham report that allegedly clears Reilly—even a redacted version, or excerpts—but Seton Hall has declined those requests.

“The goal of the Latham Report and the Responsive Action Plan was to drive change and ensure a safer, more responsive campus environment,” officials wrote in response to Inside Higher Ed’s questions about the report. “To accomplish that goal, the review relied on voluntary cooperation of numerous individuals who were promised confidentiality for the University to learn what happened.”

Title IX experts note that while the university could release the report, doing so is complicated.

Brett Sokolow, chair of TNG LLC, a risk management consultancy and law firm, said by email that several factors could be shaping the decision. One is timing, he wrote, questioning whether the university is holding onto it “to defend impending litigation.”

Sokolow added that “reports like that are a mixed bag, so they may be hesitant because some information would help them, and other information may not.” But there are also privacy concerns. While such reports can be redacted, “it also depends on how well-known or notorious the situation is,” he noted. Officials may not want to make it easy for “people to connect dots that would invade a student’s privacy, even with the redactions.”

Other experts noted other potential concerns and reasons for withholding the report.

Nicole Bedera, author of On the Wrong Side: How Universities Protect Perpetrators and Betray Survivors of Sexual Violence, told Inside Higher Ed by email she suspected that “part of the school’s hesitation to release the report is that they have exaggerated its capacity to vindicate Reilly.”

Releasing the report might also risk violating “some component of an agreement made around that case with significant consequences, such as releasing the victim from [a nondisclosure agreement],” she said. She added that universities sometimes prefer to keep such reports or case outcomes private “in part because it benefits schools to maintain control over information about how they manage Title IX,” given that such reports “could open them up to liability.”

Tracey Vitchers, executive director of It’s On Us, a nonprofit dedicated to sexual assault prevention, echoed Bedera’s last point, noting that the Title IX landscape has become increasingly litigious in recent years, making colleges hesitant to share case findings.

“My assumption would be that many institutions are taking a far more conservative approach about what they are or are not willing to release,” she said. “Not necessarily because they don’t want to hold bad actors accountable but because they recognize the legal risk that they open up themselves and any survivors or witnesses to if that information becomes public record.”

Vitchers also said it would not be uncommon for one report to find that an individual had violated university Title IX policies and for another to reach a different conclusion. That type of disparity tends to happen upon appeal, though it is unclear whether Reilly appealed the 2019 findings.

Title IX Pitfalls

Violating Title IX policies or other missteps on sexual misconduct cases have felled multiple presidents in recent years. The most famous and egregious cases were at Michigan State University and Pennsylvania State University. At MSU, Lou Anna K. Simon, who was president during the Larry Nassar sexual abuse scandal, narrowly avoided jail time after she was charged with lying to authorities about her knowledge of the situation. Graham Spanier, who served as president of Penn State during the Jerry Sandusky scandal, eventually served jail time for his failure to report allegations that Sandusky repeatedly sexually abused children on campus.

One parallel that experts drew in the Reilly case was to Joseph Castro, who served as chancellor of the California State University system and president of California State University, Fresno. Though not accused of misconduct himself, Castro was castigated for recommending a $260,000 payout to Frank Lamas, a vice president at Fresno State who was accused of sexual harassment and bullying. As president of Fresno State, Castro recommended the payout and wrote Lamas a letter of recommendation. When details of his handling of the case came to light—after Castro had been hired as chancellor of the system, which Fresno State is part of—Castro resigned amid scrutiny.

The fallout highlighted the need for reform on sexual misconduct cases across the system.

Elsewhere, F. King Alexander stepped down as president of Oregon State University in 2021 after an investigation at Louisiana State University, which he led from 2013 to 2019, found he mishandled sexual misconduct allegations and Title IX procedures. Alexander pushed back on the findings at LSU but resigned after less than a year at Oregon State amid the controversy.

Now, as pressure ratchets up on Reilly, he looks to avoid the same fate.