You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Faculty questions about a potential conflict of interest for Regent Fred DuVal have prompted legal action, which DuVal said is necessary to protect his reputation.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Arizona Board of Regents | Getty Images

As plans to fix the University of Arizona’s $177 million shortfall come into focus, faculty and administrators are trading blame over who bears responsibility for a series of financial missteps.

Last month, interim UA chief financial officer John Arnold—who also serves as the executive director for the Arizona Board of Regents—said that 61 of the university’s 81 budget units overspent. While Arnold also pointed to excessive discounting on tuition, inflation, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and other issues, his claims of academic overspending have riled faculty members.

Specifically, Arnold said colleges and divisions spent $61 million over budget.

Faculty members take issue with that assessment, arguing that the University of Arizona administration drove overspending through excessive tuition discounting and other missteps, including subsidizing a troubled athletics department that has struggled to generate revenue.

Now, with the possibility of sweeping cuts on the horizon, the UA Faculty Senate has ramped up its criticism of university leaders—including Arizona Board of Regents chair Fred DuVal, who is now threatening legal action over faculty allegations of a conflict of interest.

The bitter clash between UA’s Faculty Senate and the Arizona Board of Regents is playing out as state lawmakers advance House Bill 2735, legislation that would minimize the faculty role in shared governance and provide more power to state university presidents.

A Shared Governance Collision

After Arizona’s budget shortfall was identified in November, President Robert Robbins warned of “draconian cuts” as the university sought to correct course financially. Officials have since introduced a belt-tightening plan that, among other things, will centralize numerous departments and implement a new budget model; a freeze on hiring, travel, compensation and construction has already been enacted. Further changes—including the forewarned cuts—are still to come.

Chief Financial Officer Lisa Rulney also resigned amid the fallout, though she was given another role at the university. (Note: This paragraph was updated to clarify Rulney’s status.)

As the UA community has sought answers, a schism has emerged between university leaders and members of the Faculty Senate, who believe the blame for overspending falls squarely on the administration—and on the Arizona Board of Regents for failing to rein in runaway expenditures.

At a Feb. 19 Faculty Senate meeting, Chair Leila Hudson accused DuVal of “errors and half-truths” in an interview he gave to Arizona PBS. She suggested he was shifting blame elsewhere by inaccurately stating that the University of Arizona had a “distributed budget model”—essentially a decentralized financial approach that allowed budget units greater autonomy—a notion she disputed.

“This erroneous statement cannot go unchallenged,” Hudson said in the meeting. “By calling the disastrous and centralizing [activity informed budgeting] model a ‘distributed model,’ Chair DuVal implies to the casual listener that it is decentralized and feeds the misperception embedded in HB 2735 that faculty and shared governance are somehow responsible for management and financial troubles, which, of course, we have no purview over.”

Hudson later dialed up her criticism, raising questions about DuVal’s involvement with Amicus Investors, a defunct company that lists both the University of Arizona and Arizona State University on its website, apparently as clients. DuVal was previously listed as a managing director on the website.

“This website seems to indicate, in my opinion, that Chair DuVal was serving as the managing director of this throughout his appointment for a second term as a regent from 2019 to 2023,” Hudson said.

Noting that it was the role of the Faculty Senate to ask questions, Hudson pondered the nature of DuVal’s role at Amicus, whether it overlapped with his time as a regent, what work Amicus Investors and DuVal specifically provided for Arizona and ASU, and when those services were rendered. Hudson also raised concerns that DuVal’s involvement might constitute a conflict of interest, even as some Faculty Senate members warned the chair about potential legal repercussions of raising such a loaded question.

Now DuVal is lawyering up and threatening legal action against Hudson.

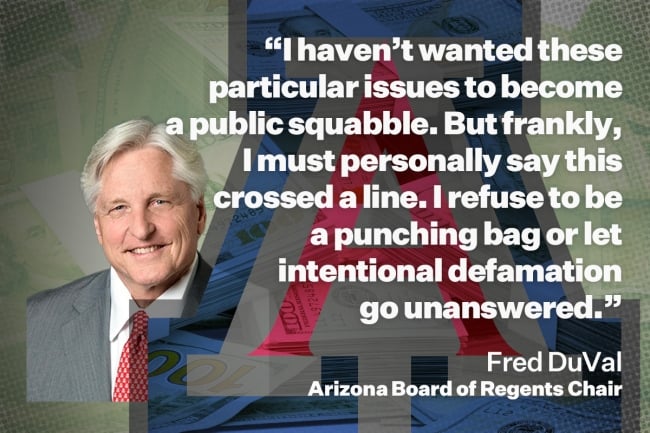

In remarks at Thursday’s Board of Regents meeting, DuVal accused Hudson of inflicting “a terrible blow to shared governance” and crossing a line with her conflict-of-interest comments. He also denied that his work with Amicus overlapped with his time as a regent.

“I refuse to be a punching bag or let intentional defamation go unanswered,” DuVal said, noting he had retained counsel and intends to “pursue legal remedies” to restore his reputation.

In the same meeting, Regent Lyndel Manson also took aim at the UA Faculty Senate, arguing that the body has been a concern for years and that current leadership has instilled a culture of fear.

“At some point enough needs to be enough, and that time is now,” Manson said, claiming the Faculty Senate has worked to destabilize the administration and refused to work collaboratively. She also questioned how representative the Faculty Senate was of the UA professoriate.

The audience met her statement with boos that were audible over the meeting live stream.

In an email to Inside Higher Ed, DuVal said that Amicus Investors was a failed venture that operated from April 2015 to August 2017 and “did not pursue or win any business in Arizona.”

DuVal, who has served two separate stints as a regent, was not on the board at the time he was involved with Amicus Investors, he said, which would invalidate the conflict-of-interest claims.

“A conflict of interest occurs when the two things overlapped and when business was conducted. Neither happened as my engagement with Amicus concluded a year before I joined the Board. A rudimentary check of my social media bios or other sources would make this clear,” DuVal wrote.

He added he was unsure why UA and ASU were listed under the “our team has worked with” section on the Amicus website. Though Amicus participated in a panel discussion “with them - and other universities” on public private partnerships, DuVal wrote, it never sought their business.

Facing defamation claims, Hudson has also obtained legal representation.

“Dr. Hudson has received the cease-and-desist letter,” Jesse Ritchey, legal counsel for Hudson, told Inside Higher Ed by email. “During the meeting, Dr. Hudson was exercising her constitutional rights and fulfilling her legal obligations when she raised these issues of public concerns. And she is now in the process of evaluating her various legal options.”

The Most Powerful Critic

While both the ABOR and the UA administration have been under fire from the Faculty Senate since the financial crisis was discovered, Arizona’s Democratic governor, Katie Hobbs, has also raised concerns and demanded reports on how the university intends to fix its fiscal issues. In addition, she requested information on UA’s purchase of the troubled for-profit Ashford University, now the University of Arizona Global Campus. Critics believe the deal, closed in 2020 for $1, added to UA’s financial woes.

In a January letter, Hobbs accused UA administrators and regents of having “no coherent vision” for fixing the university’s financial issues. She also questioned the appointment of Arnold as interim CFO and requested the two separate reports be provided this month.

Regents provided the first report, on tactics and strategies to correct fiscal issues, on Feb. 9.

The second report, released last Wednesday, shared insights into the Ashford purchase. It noted that both ABOR and university officials were aware of financial and legal risks posed by the for-profit that ran afoul of the Department of Education for misleading students, later prompting ED to forgive $72 million in student loans taken out by former Ashford students.

“ABOR and UArizona leaders took concerns regarding Ashford University’s past [regulatory] noncompliance very seriously,” board officials wrote in the report delivered to the governor.

The report noted UA “obtained repeated assurances” from Ashford’s parent company, Zovio, “that these practices had been corrected” and sought to install various safeguards, “aimed at protecting the interests of both UArizona and UAGC from the lingering consequences of the bad acts of Ashford and Zovio.”

Officials stated that UA officials “negotiated vigorously to ensure that liabilities arising from prior bad acts would remain with Zovio and not extend to UAGC or UArizona” in the agreement. Zovio was initially retained as an online program manager, but that agreement was terminated in 2022. UAGC then acquired “the OPM assets and operations of Zovio” and “ceased to have any further operational or financial relationship with Zovio,” the report noted. Additionally, all 909 Zovio employees were terminated in 2022; 791 were rehired at UAGC. However, UAGC instituted a prohibition on hiring former Zovio top executives and senior compliance employees, among other actions.

Hobbs did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed asking about the report.

Shared Governance Concerns

Amid the clash between UA Faculty Senate leaders and the Arizona Board of Regents, HB 2735 hovers in the backdrop. Faculty members from both UA and ASU spoke out against the bill in the public comments portion of Thursday’s meeting.

The bill will soon move from the Arizona House to the Senate for consideration.

Currently, the Legislature’s website lists the Arizona Board of Regents as neutral on the bill. Faculty members, however, want to see the board take a stand, even as members have decried the actions of the UA Faculty Senate and its increasingly pointed criticism.

Penny Dolin, chair of the Arizona Faculties Council, which includes members at UA, ASU and Northern Arizona University, raised concerns about HB 2735 at the ABOR meeting, noting that the proposed legislation would change the faculty’s role “from participants to consultants” in shared governance and centralize power in the hands of university presidents and regents.

Shared governance, Dolin argued in her remarks to the Board of Regents, “presents the surest way to guarantee the best outcomes for our students and the people in the state of Arizona.”