You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The international student market is shifting to South Asia and Africa as interest from China wanes.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

International student enrollment grew by 6.6 percent in the 2023–24 academic year, surpassing pre-pandemic levels for the first time, according to a new Open Doors report from the Institute for International Education. Mirka Martel, IIE’s head of research, said on a press call last Wednesday that the 1,126,690 international students in the U.S. last year were the most since IIE began keeping track.

International students accounted for 5.9 percent of the total U.S. higher education population in 2023–24. But the number of first-time international students only grew by 0.1 percent, a marked difference from the 14 percent increase in first-timers in 2022–23, when the total international student population grew by 17 percent.

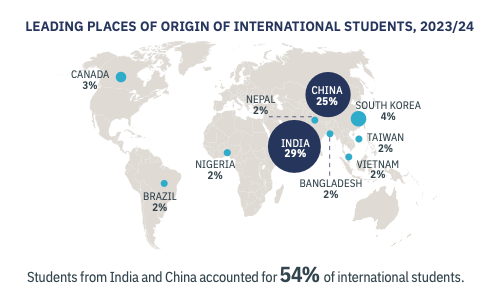

For the first time since 2009, China was not the top source of international students in the U.S. That spot now belongs to India, which saw a 23.3 percent increase; Indians now make up just shy of 30 percent of foreign students enrolled at American universities. International enrollment from China fell by 4.3 percent over all and 12.8 percent at the undergraduate level, a precipitous decline that builds on years of waning interest from Chinese applicants. Despite this, China remained the No. 1 source country for undergraduate students.

Martel said the shift could be attributed to a combination of long-term consequences from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as a confluence of other factors, including increased capacity and improved quality of higher education in China.

The report found pronounced growth in students from several other South Asian and African countries. Ghanaian student enrollment skyrocketed by 45.2 percent, for example, and the number of students from Bangladesh, Iran and Nigeria increased by 26.1 percent, 15 percent and 13.5 percent, respectively.

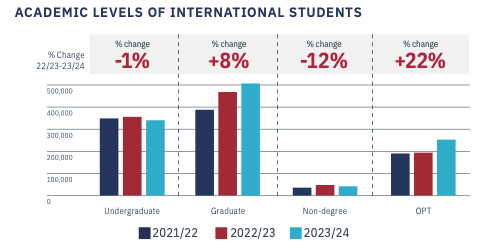

Institute for International Education

The overall rise in international enrollment was fueled by a 7 percent increase in graduate students, while undergraduate enrollment declined by 1.4 percent. Though the number of international graduate students is the highest it’s been in years—more than 500,000, up from 375,000 in 2019—the undergraduate international population is at a five-year low of 342,000, with about 70,000 fewer students than in 2019. The number of students participating in Optional Practical Training, which allows international students to work in the U.S. for up to three years after graduating, grew by 22 percent.

As graduate students replace undergraduates in enrollment growth and India supplants China at the top, the field of international recruitment and admissions is changing rapidly. Rajika Bhandari, principal of the international education firm Rajika Bhandari Advisors and co-founder of the South Asia International Education Network, said colleges should prepare.

“Institutions must diversify their recruitment efforts, and many are. But they cannot be complacent,” she said. “If they understand and react to the new landscape—more grad students and short-term degree seekers, more from South Asia and Africa, fewer undergraduates—it should be less of a stress factor.”

The Open Doors Report on International Education | Institute for International Education

According to the report, the majority of international students in the U.S. studied in a STEM field, and the top state destinations were California, New York and Texas; numbers remained fairly stable in California and New York, but Texas saw an 11 percent increase in international enrollment. The top institutions enrolling international students were New York, Northeastern and Columbia Universities. Of the top 15 destination universities for foreign students, 11 were public.

The report’s data on American students studying abroad for the 2022–23 academic year—which runs a year behind the international student data—showed a 41 percent increase from 2021–22, rebounding to just shy of 2019 levels.

The majority of American students studied abroad over the summer, while 34 percent spent a full semester out of the country. The top field of study for students abroad was business and management, pursued by 21 percent of the study abroad population, followed by social sciences at 18 percent.

The top destinations for American students remained the same as in recent years, with Italy in the No. 1 spot followed by the U.K., Spain and France.

Facing Future Headwinds

While the numbers indicate significant changes to the international student landscape, a number of building headwinds may stunt growth from countries like India and Bangladesh.

International student visa denials are on the rise; in 2023 the State Department rejected 36 percent of all student visa requests, and visas from India and Africa were much more likely to be rejected than those from China or Europe, according to a report from the Cato Institute. While the Open Doors report uses data from the previous academic year, a recent report using data from this fall found that international enrollment at U.S. universities is down about 6 percent, and that clampdowns on student visas had a major impact.

“[International enrollment] is such a rapidly shifting landscape that we’ve already moved beyond these numbers,” Bhandari said. “It’s hard to say where the status quo is going to end up.”

As Donald Trump and the Republican Party prepare to take over the White House and Congress, those numbers may fall even further. The last Trump administration proposed major rule changes to student visa processes and restrictions on OPT and postgraduate work visas. While most of those proposals never became policy, Bhandari worries they have a better chance of being enacted this time around.

“Student interest—from India, from Ghana, from Bangladesh, from Vietnam—is clearly strong,” she said. “But it’s going to depend on whether the U.S. projects that it wants them or that it’s going to engage with the rest of the world through its universities.”

Plenty of factors outside politics could also complicate institutions’ ability to capitalize on the explosion in interest from South Asian and African students. The visa processes in those countries are more complicated and susceptible to corruption, which can lead to wasted resources and bureaucratic hassle for colleges. And unlike students from China, Japan or Europe, students from the Global South are also more likely to need significant financial support. While the Open Doors report found that 84 percent of institutions had increased their investment in international recruitment initiatives like financial aid, Bhandari emphasized that such support needs to be sustained.

“Most future growth in the international enrollment space will come from the Global South,” Bhandari said. “That’s also where it’s hardest for students to afford a U.S. higher education.”