You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

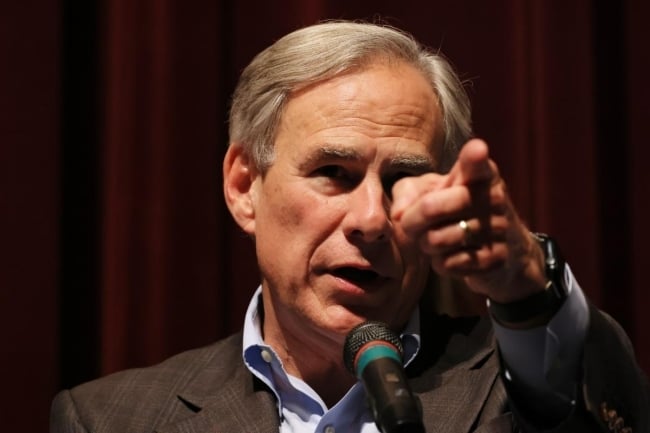

Texas, under Republican governor Greg Abbott, is one of the states where lawmakers have proposed banning tenure at public colleges and universities.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Over the past two years, lawmakers in at least 10 states have pushed legislation that would weaken—or outright eliminate—tenure in public colleges and universities. With the exception of a Democratic state senator in Hawai’i, these bills have all been pushed by Republicans in states such as Texas where the party controls the Legislature.

Despite these proposals, no state has actually gone through with fully banning tenure from its public colleges and universities. The bills that would’ve done so either failed to pass or were watered down before passage after facing opposition from faculty members, who stress that tenure protects academic freedom, including for conservatives, and from university leaders, who say it helps recruit professors who could make more outside academe.

But state lawmakers may keep pushing, perhaps encouraged by their national counterparts in Congress calling for universities to punish allegedly antisemitic professors and by the rise of a GOP vice presidential nominee who’s called professors “the enemy.”

“This is extremely alarming for academic freedom,” said Anita Levy, a senior program officer in the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance. Faculty members who lack tenure “teach in precarious positions,” she said, and don’t “have economic security and may feel that they need to either self-censor or revise their curricula or their teaching methods.”

With the likelihood of more tenure-ban bills in the future, the authors of a forthcoming article in The Review of Higher Education look farther back at the history of such legislation. They identified 13 tenure-ban bills from 2012 to 2022, starting with one in Oklahoma and eventually spreading to five other states: Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina and West Virginia.

The number of ban bills rose over time, according to the peer-reviewed article. The authors also looked at some state-level economic, educational and political factors in states where this legislation appeared. They didn’t determine whether these factors actually led lawmakers to file these bills, but they did conclude that the chance of a ban bill being introduced was nearly five times greater in states where Republicans controlled the whole Legislature and the governor’s office.

The authors also found that a one-percentage-point increase in a state’s unemployment rate “was associated with a 68 percent reduction in the risk of introducing a tenure ban”—suggesting, they wrote, that financial concerns weren’t really what was driving lawmakers to target job protections for faculty members. Some scholars, they note, have “understood 21st-century threats to the tenure system as reflections of political and social divisions rather than responses to harsh budgetary realities.”

The study also found that a lower percentage of adults with bachelor’s degrees, and a lower percentage of white students at a state’s flagship university, were both correlated with a greater chance of a tenure-ban bill appearing. “Tenure bans appear to reflect the deep cleavages that characterize much of public life in the 21st century U.S.,” the authors wrote.

But looking only at attempted tenure bans is a limited way of viewing this trend, as the authors acknowledge. The more complex picture may be too much for a single empirical study, because there are many creative ways for policymakers to weaken tenure while still saying they didn’t kill it. And they’ve been increasingly busy—and successful—at doing just that.

Beyond the Bans

If you thought there had to be more than 13 proposals targeting tenure over the study’s 11-year period, you’re right. The authors limited their study to just legislatively proposed bans that would end tenure within all or part of a state higher education system. They acknowledge that definition excluded some high-profile moves that weakened tenure.

The AAUP says 68 percent of U.S. faculty members held what it calls contingent (nontenured and non-tenure-track) appointments in fall 2021, compared to about 47 percent in 1987.

In 2015, Wisconsin governor Scott Walker and a Republican-controlled Legislature removed tenure protections from state law, allowing university leaders to chip away at it. The authors didn’t count this as a tenure ban, though they did count three bills from West Virginia, in 2018, 2019 and 2020, that also wouldn’t have ended the practice on their own. These bills would’ve authorized the governing boards of public colleges and universities to eliminate tenure but wouldn’t have forced those boards to do so.

The past two years further showed the drawbacks of only looking at tenure bans when trying to understand the weakening of tenure. In March, Indiana’s GOP-controlled Legislature passed, and its governor signed, a law saying that public colleges and universities must deny tenure to faculty members who, “based on past performance or other determination” by the institution’s Board of Trustees, are “unlikely to foster … intellectual diversity.” Those boards will get to define what “intellectual diversity” means, and that criterion will also be considered in the post-tenure reviews that the law newly requires every five years.

In 2023, the North Dakota House’s top Republican filed a bill—which the House then overwhelmingly passed before it narrowly failed in the Senate—that would’ve allowed the presidents of Dickinson State University and Bismarck State College to fire tenured faculty members without any review from a faculty committee. That would be a fundamental departure from the AAUP’s widely adopted definition of tenure. (In contrast, not a single legislative committee passed any of the three West Virginia bills.)

Also excluded from the study were actions by nonlegislative policymakers that have diminished, or threaten to diminish, tenure’s protections. Despite the North Dakota bill’s failure, the State Board of Higher Education has been considering far broader reductions to tenure protections than the legislation would have implemented, possibly affecting 11 public higher education institutions instead of just two.

In 2022, the AAUP censured the University System of Georgia for post-tenure review changes that decoupled such reviews from dismissal policies and their due process protections. That gave universities the new power to fire professors without them receiving a hearing led by their fellow faculty members.

Levy noted also that “we’ve seen internal attacks” on tenure: higher education institutions themselves “making tenure more tenuous, so to speak.” Some university leaders have said tenure prevents them from responding quickly enough to budget crises or the need to offer students new academic programs.

While West Virginia hasn’t banned tenure, its flagship university axed tenured faculty members last academic year as part of a larger tranche of layoffs and program cuts. West Virginia University did this all without officially declaring the financial exigency status that the AAUP says universities should announce, in a decision made alongside their faculty members, before possibly forcing out tenured professors.

Bills to ban or weaken tenure don’t look to be slowing down anytime soon. But even without lawmakers targeting tenure, it’s in trouble going forward.

At the root of it all, Levy said, is a “demonization of higher education faculty.” Attacks on tenure are just part of a broader right-wing attack on higher education that’s taken hold in some state legislatures and in political discourse on the right, she said.

But lawmakers could also further erode tenure by inaction. Not putting more funding into higher education would continue to leave colleges and universities scrambling to cut low-enrollment programs and create new ones to attract students—all of which tenure may stand in the way of.