You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

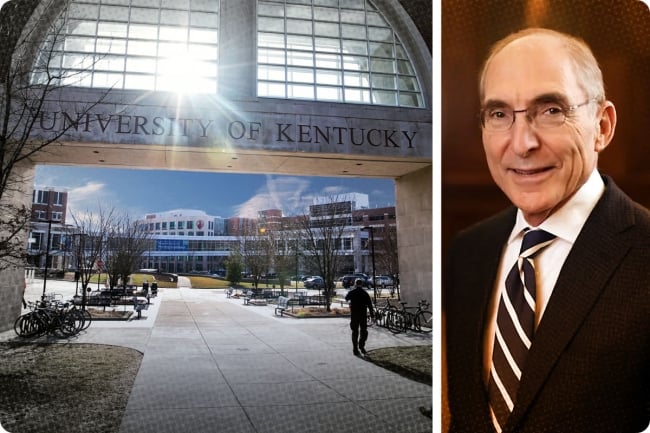

University of Kentucky president Eli Capilouto and his Board of Trustees have pushed to eliminate the University Senate.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky Board of Trustees is set to vote next week on a controversial proposal, backed by the UK president, to dissolve its University Senate, which is more than 100 years old. That imperiled body is composed chiefly of faculty members and has the substantial power to, among other things, approve or reject new academic programs and courses.

The board is proposing to have a faculty senate instead—one that couldn’t shoot down courses and programs and would instead be advisory. While university leaders have said the move is partly about increasing the role of students and staff, the board is at the same time assuming ultimate power over educational policy.

University president Eli Capilouto has stressed the importance of making curricular decisions at the college and academic unit level. Those lower-level decisions currently go to the University Senate for its consent or refusal, but the new paradigm wouldn’t get rid of a middle level completely. Instead of the University Senate, the provost would rule.

But with approval of such a significant change apparently imminent, with only one “no” vote cast in a preliminary greenlighting by the board in April, faculty members who support the University Senate are still asking a basic question: Why are university leaders pushing this change?

“No one knows,” said Philipp Rosemann, president of UK’s American Association of University Professors (AAUP) chapter. Rosemann, who’s also the Cottrill-Rolfes chair of Catholic Studies, said university leaders have a “certain mantra that they repeat: ‘We need to accelerate our progress’ in how the university ‘advances the commonwealth.’”

“The question is what that means,” Rosemann said. He said he thinks the answer will only emerge over the 12 months following the change. “I do not think that the university administration and the Board of Trustees have shown their hand on this,” he said.

“We all wonder what is the real reason, because the purported reason can’t be it,” said Douglas Michael, the newly elected chair of the executive council of the University Senate. Michael said he expects the board will make the change effective immediately. “A week from Friday there will be a giant power vacuum,” he said, adding that “there are, oh, maybe 80 different course proposals sitting in the pipeline waiting for approval.”

Even Hollie Swanson, one of the faculty’s two elected representatives to the board, said she doesn’t know why the other board members and the president are pushing the change. “That is the question we have all been asking,” Swanson said. “The faculty have asked [the] president that numerous times and we’ve never really gotten a satisfactory answer, and we’ve also asked, ‘Why the rush?’”

Swanson said she’d also asked her fellow board members, and “I don’t get an answer there either.” She was the only board member to vote against advancing the proposal in April.

Capilouto was traveling Tuesday and couldn’t provide an interview, university spokesman Jay Blanton said. Pressed on what the university is trying to accomplish and how the currently constituted University Senate stands in the way of those goals, Blanton didn't provide specifics.

“I don’t think it’s about obstacles, I think it’s about doing better,” Blanton said. “I don’t think there needs to be a better reason than wanting to serve the commonwealth better.”

Rosemann said faculty members should have ultimate authority over curricular matters “because they are the experts.” He said “there is an increasing number of institutions where the role of faculty is limited to being advisory.”

The University Senate voted no confidence last month in Capilouto and the proposals. Capilouto has led the university for more than a dozen years, and Rosemann said that “Capilouto up to this point has been popular among the faculty.”

“Why is he risking his reputation?” Rosemann asked. He said Capilouto “will be remembered now as the president who abolished faculty governance.”

‘Poorly Justified’

Michael dated the start of the effort to abolish the University Senate to October, when the board passed a resolution, titled “Accelerate Growth to Do More And Be More for Kentucky,” directing Capilouto to accomplish five broad “mores.” “Nobody knows why,” Michael said.

“More Educated Kentuckians,” was the first “more” the board wanted to see. The explanatory paragraph focused on “strategic” enrollment growth. The others were: “More Readiness,” which dealt with revising the general education curriculum; “More Partnerships,” which broadly advocated more partnerships and “acquisitions”; “More Employee Recruitment and Retention,” which focused on improving those areas; and “More Responsiveness,” which talked about being “aligned with the state’s needs.” (The resolution said the board expected “significant progress” by this month. Neither the board chair nor its vice chair returned requests for comment Tuesday.)

In late February, the plot thickened and controversy emerged when the board passed another resolution directing Capilouto to “move quickly to formulate recommended changes to our Governing Regulations for this board’s consideration at the next meeting.” The board asked for, among other things, changes that “clearly articulate a shared governance structure … that clearly recognizes the board’s primacy as the institution’s policy making body.”

That next meeting was in April, when Swanson made a statement alongside her “no” vote. “This board has heard countless appeals from those who care deeply about our university,” Swanson said, according to the written statement she provided Inside Higher Ed. She mentioned pleas from the University Senate, the AAUP, faculty emeriti, alumni and others.

“All of these appeals consistently message that removing educators from educational policy decision making is unwise and defies logic,” she wrote. “I will be voting ‘no’ in these ill-conceived, poorly justified and most importantly, rushed actions.” The university, for its part, has said faculty members will still be involved in an advisory capacity.

The board outvoted her. Then on May 6, according to Michael, the University Senate voted 58 to 24 with 11 abstentions to express “no confidence” in the president. “I would have nothing but great praise for him up until this last fall,” Michael said.

Still, university leaders have pressed on.

In an op-ed last month in The Kentucky Lantern, Capilouto expressed the need for broad governance changes. His arguments criticized current processes, but he never mentioned the University Senate by name.

“As I have talked to hundreds of people across our campus, I heard repeatedly the desire to be more involved, but the inability to do it under the current rules and governance structures,” Capilouto wrote. “Too often, the voices of students and staff, specifically, were discounted or not heard at all in our current governance processes and structures. And too many faculty feel hamstrung by cumbersome rules and byzantine processes.”

Capilouto advocated for “adding more voices to the table.” He wrote that “faculty at the college level know best what’s happening in their fields and how to be more responsive to our state’s needs.” The changes, he promised, would “clarify and streamline the rules, making authority and responsibilities easier to understand and approvals for new programs more manageable to negotiate.”

Among Capilouto’s proposals is to create a President’s Council, which would include an equal four faculty members, four students and four staff. It would also only be advisory.

While the university hasn’t provided specific examples of the University Senate impeding the institution, some individuals have supplied them.

More Input for Staff, Students?

The Kentucky Lantern reported that some faculty members spoke at the April meeting in favor of the changes, including Hubie Ballard, the other faculty representative on the board, who said it’s important for staff and students to have input. (Michael has said the Senate has 94 faculty members and about 16 students, and half of the top administrators rotate in and out each year.)

Others quoted in The Lantern were faculty members—but also deans. One was Chipper Griffith, dean of the College of Medicine, who spoke to Inside Higher Ed. Griffith said the biggest reason “I’m excited about the change is it’s going to empower local faculty in colleges to make decisions that affect only the college.”

Griffith’s college tried to add biochemistry to its prerequisites for students a couple of years ago, but University Senate approval took more than a year, he said. If the college’s faculty members were allowed to decide that alone, Griffith said, the prerequisite addition “could happen the next day.”

But Rosemann, with the campus AAUP chapter, noted that the colleges’ decisions, once the University Senate is gone, will go to the provost instead for sign-off. What will actually be different, Rosemann said, is that “effective approval of these changes” will rest with deans and provosts.

The Student Government Association (SGA) passed a resolution April 3 supporting the changes, saying that “repeated efforts for student advocacy have been dismissed by the University Senate.”

John Hurley, a graduate at-large SGA senator who stressed he wasn’t speaking for SGA as a whole, said that “in practice, the University Senate is a faculty senate that sets policy for faculty, students and staff.” Hurley said that among the University Senate’s imposed rules was that the student senators who jointly served on the University Senate have to be at least upper-classmen. “I, for one, thought that one was ridiculous,” he said.

Hurley said the student government basically has to go to the administration to get things done. Now, close to its demise, he said the University Senate has offered to add more student representatives. “The time to fix that was years ago, the time to update shared governance, the time for them to listen to us was before I was even a student at the university, not on their way out making concessions because their time was up,” Hurley said.

Mark Criley, a senior program officer in the national AAUP’s Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, said UK’s move to abolish the University Senate is highly unusual for a university of its “stature and reputation.” Instead of university leaders unilaterally changing faculty governance structures, he said, faculty members “should have a very active role in designing and implementing, or indeed replacing, those governing bodies for faculty.”