You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

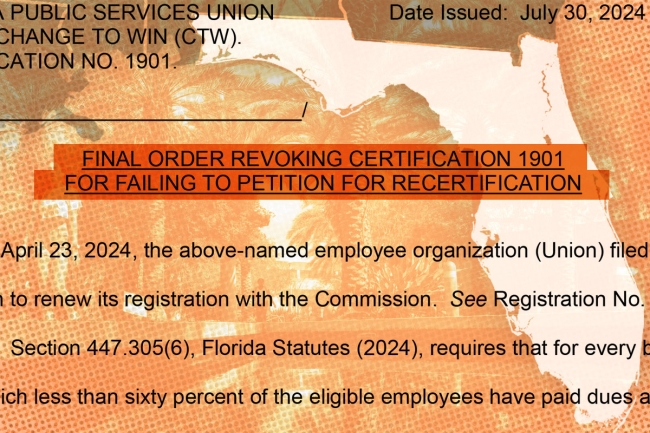

Eight adjunct unions have been decertified under a Florida law passed last year.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Thomas Simonetti/The Washington Post/Getty Images

All eight unions representing adjunct professors at public institutions in Florida have been decertified in accordance with a new state law, affecting more than 8,000 faculty members.

The adjunct unions—uncommon across higher education until recently—were all established within the past five years and celebrated as rare victories for low-paid adjuncts in a right-to-work state. But now, a law passed by Florida’s Republican-dominated legislature last year—Senate Bill 256—has upended the unions, all of which lost certification last month, public records show. More than 20 bargaining units for noninstructional staff, working in areas such as groundskeeping and other roles, were also decertified earlier this year.

The eight unions represented adjunct professors at Broward College, Hillsborough Community College, Miami Dade College, Seminole State College, St. Petersburg College, University of South Florida, Lake-Sumter State College and Valencia College.

The issue that prompted decertification is a requirement in SB 256 that 60 percent of workers in the bargaining unit must pay dues to maintain their union representation. The legislation also barred members from paying membership dues through automatic paycheck deductions, which critics have alleged is an anti-union tactic to weaken the strength of bargaining units.

The Political Context

Though not specifically focused on higher education, SB 256 was one of several bills passed in Florida last year that raised concerns about political intrusion into academe. In recent years, lawmakers in the state have loosened transparency around presidential searches, restricted instruction on race and gender, weakened tenure, and defunded diversity, equity and inclusion programming.

At the same time, Florida governor Ron DeSantis has appointed political activists to the New College of Florida Board and tasked members with driving a conservative turnover at NCF. Florida has also tapped several former Republican lawmakers to lead state institutions.

Labor officials and activists have warned of the potential consequences of SB 256, a bill they’ve described as anti-union, since it was first introduced in Florida, which is a right-to-work state. Now organizers’ fears have been realized.

Many of the adjunct unions that were decertified fell dramatically short of the 60 percent threshold, according to a public database created by WLRN, an NPR affiliate in south Florida. The Lake-Sumpter adjunct union had no dues-paying members, according to WLRN’s database. Others, such as Miami Dade and St. Petersburg College, had less than 1 percent of members paying dues. Broward College, at almost 22 percent, had the highest participation rate.

Adjunct faculty representatives at affected campuses did not respond to requests for comment from Inside Higher Ed, nor did Service Employees International Union, the national organization that represents the unionized adjuncts as well as thousands of other workers across the U.S.

Some adjunct faculty members told Orlando Weekly, which first reported the decertification news, that they expected the outcome.

DeSantis, who championed SB 256, also did not respond to a request for comment. But the governor and failed Republican presidential candidate previously cast the legislation as a necessary step to rein in special interests and give more power and money to employees.

“For far too long, unions and rogue school boards have pushed around our teachers, misused government funds for political purposes, taken money from teachers’ pockets to steer it for purposes other than representation of teachers, and sheltered their true political goals from the educators they purport to represent,” DeSantis said when he signed SB 256 last spring.

In the same statement, Florida Commissioner of Education Manny Diaz, Jr. celebrated the new law as a win against “truly divisive unions” which he accused of “hiding their true purposes.”

The Fallout

When adjunct faculty members began organizing efforts that led to unionization, they emphasized higher wages, job security and the overall improvement of higher education. Progressive publications highlighted the movement as a labor win in a deep red state.

Now, after hard-fought wins across eight campuses, those unions have met a sudden end.

What’s next is unclear, said Andi Clemons, director of Academic Affairs, Administration, and Budget at Florida Gulf Coast University who has written about unionization trends and SB 256.

“When a union is decertified, employees may lose some rights and benefits, or they may not. It’s hard to tell, and we do not know what will happen. They will still exist as an organization but not have the authority to bargain and create a contract because they are no longer the recognized bargaining agent of the employees at these institutions. It could mean changes in processes, contract terms, and the ability to have a voice in matters they perceive as violating procedures,” Clemons wrote by email.

But so far, according to college officials at four of the eight institutions that responded to inquiries from Inside Higher Ed, little seems to have immediately changed after decertification.

“Because the union has been decertified, the union is no longer the exclusive bargaining agent for the adjunct faculty included in the bargaining unit. Accordingly, the College is no longer obligated to collectively bargain with the union over the terms and conditions of employment for these adjunct employees. The College will review the collective-bargaining agreement and consider what terms in the agreement might be incorporated into College policy/procedures,” Seminole State spokesperson Kimberly Allen wrote by email.

Officials at Broward College, Hillsborough and St. Petersburg all provided similar statements noting that, while agreements with unions are null and void, nothing has changed at the moment.

Still, some experts expressed concern about the decertification process.

William A. Herbert, distinguished lecturer and executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College of the City University of New York, pointed to the shifting nature of faculty in recent years. While tenure-track faculty once made up the majority of the professoriate, it is now mostly adjuncts.

Contingent faculty now comprise nearly 70 percent of the teaching ranks across higher education, according to data from the American Association of University Professors. Adjunct faculty are notoriously underpaid compared to their tenured peers and have few protections.

And, increasingly, adjunct faculty members have been organizing, Herbert said.

Herbert believes that a state unilaterally decertifying a union, without the represented workers having a say, is undemocratic and “should be looked at as being part and parcel of other attacks that we’ve seen around the country, whether it’s workplace democracy or political democracy.”

Clemons noted that there is a process to regain certification. An organization can do so by collecting interest cards from 30 percent of represented employees within a month of their certification deadline. Once those cards are submitted, Florida’s Public Employee Relations Commission will hold an election “in which a majority of the voters must opt to keep their union.”