You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

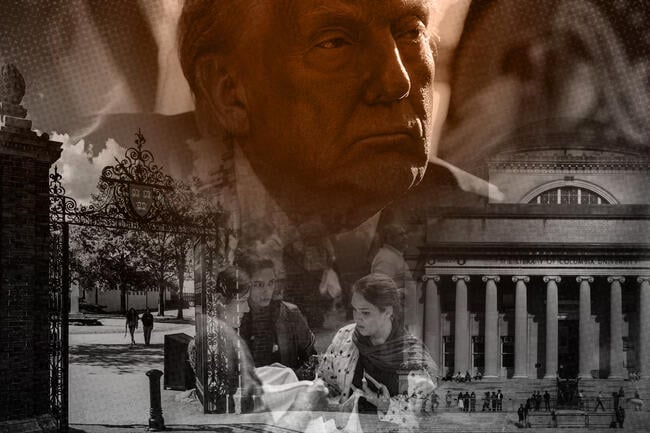

The Trump administration now looms over the Columbia and Harvard university campuses.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Andrew Harnik and Alex Kent/Getty Images | Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto/Getty Image | APCortizasJr/iStock/Getty Images

Last week, the Trump administration ordered Harvard University to take multiple steps to continue having a financial relationship with the federal government. Among the demands was to review and make “necessary changes” to “address bias, improve viewpoint diversity and end ideological capture” in “programs and departments that fuel antisemitic harassment.”

Trump officials weren’t more specific in their letter to Harvard about which programs and departments they think fuel antisemitism, why or what changes are needed, and the president’s administration didn’t provide Inside Higher Ed more details. But before that April 3 letter arrived, Harvard officials had already shaken up the leadership of the university’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies and halted two other Middle East–related programs.

That—combined with Columbia University’s plan to review Middle East programs while facing federal funding cuts—has fed worries among scholars in this area at other universities about threats to their academic freedom. Pushes within and outside academe to address alleged antisemitism, or an alleged lack of pro-Israel views, predated Trump’s second term. But those campaigns ramped up after the current Israel-Hamas war began Oct. 7, 2023, and Trump’s return to power has now added the specter of actual funding cuts to the pressure on institutions.

“Anybody working in Middle East studies now feels very anxious,” said Aslı Bâli, president of the Middle East Studies Association and a tenured law professor at Yale University.

Bâli said university administrators are concerned about academic programming and campus expression that might draw public scrutiny “in such a way that they might be the next to be targeted by the Trump administration.” This, she said, “creates a climate of intimidation and fear, which in turn produces vulnerabilities for centers of Middle East studies.”

None of us wanted this. We’re all academics … none of us wanted to be in the media constantly.”

—Columbia faculty member

Incidents in the Ivy League

The Harvard Crimson student newspaper reported that, on March 26, David M. Cutler, interim dean of social science, dismissed the director and associate director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, an interdisciplinary entity established in 1954. Neither of the now-former leaders, who both retained their faculty jobs, responded to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment.

In a news release, Harvard’s American Association of University Professors chapter said that Cutler, in explaining the dismissals, alleged there was “a lack of balance and multiple viewpoints in the Center’s programming on Palestine.” In an email to Inside Higher Ed, a Harvard spokesperson said Cutler “raised the issue of ensuring more voices are heard in the study of the Middle East,” but he “disputes any portrayal” that he attempted “to limit certain points of view.” The spokesperson said the ousted director—Cemal Kafadar, Vehbi Koç Professor of Turkish Studies—was already on sabbatical this academic year, and the same interim director and administrative staff remain in place. The spokesperson did not mention the dismissed associate director, Rosie Bsheer.

Around the time of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies shakeup, the Crimson revealed that Harvard had decided not to renew a partnership with Birzeit University in the Palestinian West Bank—though a Harvard spokesperson told Inside Higher Ed that memorandum of understanding expired months ago. Also, The National Catholic Reporter recently reported that Harvard cut the last position in its Religion, Conflict and Peace Initiative, which had focused on Israel and Palestine. The Harvard Divinity School announced March 28 that it was pausing the initiative after it lost financial support; the Reporter said that announcement came after students were interviewed about the program.

There had been controversy further back in Harvard’s broader Religion and Public Life Program. The Crimson reported that the associate dean overseeing it abruptly retired in late January, and the assistant dean announced the next day he would resign. The assistant dean alleged the university interfered in programming and condoned “hate against Muslims and Arabs,” the newspaper wrote.

All of these Harvard programs had faced criticism as being biased against Israel or Zionism, though none were specifically called out by the Trump administration. It’s unclear whether there’s any connection between Harvard’s actions and the Trump administration’s vague, after-the-fact public demands.

Meanwhile, at Columbia, federal officials demanded that the university place the Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies Department (MESAAS) into academic receivership. That demand came after the federal government cut $400 million in grants and contracts to the institution last month.

In response, Columbia said it would appoint a new senior vice provost to do a “thorough review of the portfolio of programs in regional areas across the university, starting immediately with the Middle East”—a review that goes beyond MESAAS, roping in the Center for Palestine Studies and more. Columbia’s AAUP chapter generally decried that review, but then–interim university president Katrina Armstrong told faculty that the move meant MESAAS wouldn’t be put into academic receivership for the minimum five years Trump officials demanded, according to a transcript of the meeting obtained by The Free Press. (Armstrong has since stepped down.)

So what’s actually happening with MESAAS at Columbia? “I’m still trying to figure things out,” Gil Hochberg, the department’s chair, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed Monday. “Like everyone else, I have been following the events of the past three months with growing dismay and confusion.”

Hochberg said the department “remains committed—as it always has been—to the highest standards of scholarly inquiry and pedagogical integrity. As we continue to do our work, I trust that the university will stand by its core of academic values, of academic freedom, that are at the basis of our common endeavor.”

Bâli said last week that she hasn’t seen any other public actions taken against Middle East programs beyond Columbia and Harvard. But she said she thinks the Trump administration’s goal at Columbia was to set “examples, including examples requiring university administrators to directly intervene not just in free expression on their campuses, but also even on academic programming that might be deemed critical of Israel. And that’s truly extraordinary.”

But why was a specific academic department at Columbia targeted by the Trump administration? The federal government hasn’t said. But there’s a history at Columbia, one that might be part of a broader trend in academe regarding views on Israel.

“This goes way back,” said Miriam Elman, executive director of the pro-Israel Academic Engagement Network.

From Edward Said to Joseph Massad

At Columbia, “it’s a long story,” said one faculty member there who wished to remain anonymous. He started the story with Edward Said, the late Palestinian American Columbia professor whose seminal work and activism promoted the Palestinian cause. Said’s writings were “incendiary” because they challenged the dominant pro-Israel narrative, which has now been discredited in academe and among young people, the anonymous faculty member said.

A non–full professor within MESAAS itself, who also wished to remain anonymous, said they think the department, despite being interdisciplinary and “transregional,” was targeted partly because it’s a leader in the study of Palestine, building on Said’s legacy and the work of current faculty members.

Another person to point back to Said was Shai Davidai, a Jewish and Israeli assistant business professor at Columbia and counterprotester against what he calls the “pro-Hamas” campus protests following Oct. 7, 2023. (Davidai said he’s still suspended from teaching and from campus after the university said he harassed and intimidated employees.) Davidai said Said is treated as a “prophet rather than academic leader.”

“You kind of have an alignment of individuals with a certain point of view at this department throughout the years,” Davidai said. He called MESAAS “ground zero, you could say, of everything that’s been going on.”

In 2004, the year after Said’s death, the university became embroiled in the Columbia Unbecoming controversy, which surrounded allegations that pro-Israel students were being harassed in some Middle East courses. Columbia Unbecoming, a documentary, aired student complaints against faculty, including current professor Joseph Massad. In 2005, a university faculty committee largely cleared the Middle East professors of charges that they were intimidating students—though it found “credible” a report that Massad had once shouted at a student and urged the student to leave the classroom.

There have been other flare-ups at Columbia in the two decades since that documentary, including over Massad’s ultimately successful battle for tenure and a 2023 effort opposing the university’s plan to establish a center in Tel Aviv. But then came Oct. 7, 2023.

Bâli said “external actors” have been “waging campaigns to mobilize alums, to alert donors, to swamp university offices, to initiate lawsuits, etc., alleging that academic programming or other work at universities that has to do with Israel represents a bias or form of discrimination.” She said, “The censorious pressure has accelerated dramatically since Oct. 7,” and that she thinks “articulate public intellectuals able to explain the Palestine perspective” are “an intolerable proposition” for some.

But she also said the public record suggests “internal actors” at the university were involved alongside the external ones in “targeting any form of criticism of Israel on the campus of Columbia. That resulted in scrutiny inevitably falling on the Middle East studies department.”

Massad, a professor of modern Arab politics and intellectual history in MESAAS, was widely criticized for an article he published the day after Oct. 7, 2023, in The Electronic Intifada. Writing of the Hamas attack, Massad said Israeli settlers “may have finally realized that living on land stolen from another people will never make them safe,” and labeled as “awesome” the “scenes witnessed by millions of jubilant Arabs who spent the day watching the news, of Palestinian fighters from Gaza breaking through Israel’s prison fence or gliding over it by air.”

The autumn of campus protests led up to congressional investigations of alleged antisemitism on campuses and televised Capitol Hill grillings of elite university presidents—including the April hearing with then–Columbia president Minouche Shafik. A Republican congressman asked Shafik specifically about Massad and his article; an earlier letter from the House Committee on Education and the Workforce had criticized him and another MESAAS professor.

Elman, of the pro-Israel Academic Engagement Network, said the answer to addressing the anti-Israel bias she sees isn’t to remove faculty but to “add more faculty with diverse opinions, add more courses.” But she said she sees issues across the humanities more broadly and in some social sciences.

“Ironically, it’s actually been other disciplines, other departments, where we’ve seen this—more so even than in Middle Eastern studies,” Elman said.

The anonymous MESAAS faculty member said, “I still have hope that the university and the larger community will continue to fight for academic freedom.”

“None of us wanted this,” they said. “We’re all academics … none of us wanted to be in the media constantly.”

(The story was corrected to cut a quote misattributed to Bâli.)