You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Indiana’s attorney general is arguing that public university professors’ classroom speech is government speech.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana

In February, Republican lawmakers in Indiana passed a law saying public colleges and universities must deny tenure to professors who are “unlikely to foster … intellectual diversity.” The legislators left it to university trustees, many of whom are appointed by the governor, to determine what intellectual diversity actually means for faculty members and whether they have provided it.

Professors who earned tenure before the law’s passage aren’t spared from its implications. The statute says that whether they fostered intellectual diversity, and whether they “introduced students to scholarly works from a variety of political or ideological frameworks,” will now be considered in post-tenure reviews required every five years. A bad review could mean losing both tenure and employment.

In May, four faculty members from Indiana and Purdue university campuses sued to invalidate those parts of the law. The American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana, representing them, wrote in the lawsuit that these provisions impinge upon their First Amendment right to “academic freedom to determine the content of and deliver their instruction, free from interference by the State.”

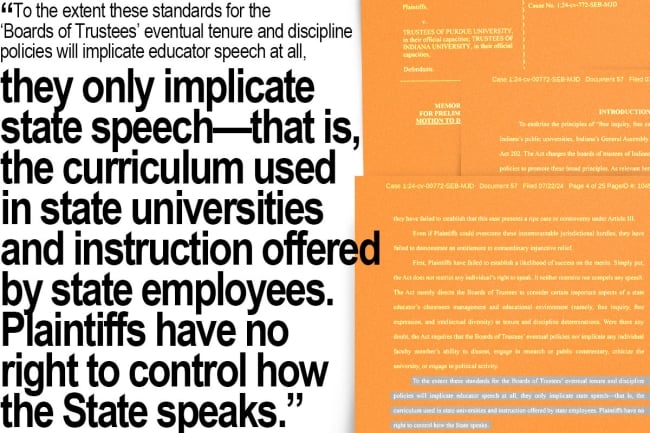

But Indiana’s attorney general, Republican Todd Rokita, argues that the professors have no such First Amendment right. In an echo of Florida’s ongoing defense of its own legislative attempts to regulate public university classrooms, Rokita’s office wrote in a brief to the federal court that “the classroom curriculum of a public university is government speech set in accordance with State law.”

“The curriculum used in state universities and instruction offered by state employees” is “state speech,” the attorney general’s office wrote, and “plaintiffs”— the professors—”have no right to control how the State speaks.”

The state says the professors are “claiming a brand new, state-university specific ‘First Amendment right to academic freedom.’”

That last line is one of the “gratuitous stupidities” in the attorney general’s brief, wrote Steve Sanders—an Indiana University at Bloomington law professor who’s not involved in the case—in an essay on Medium Friday. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized decades ago that the First Amendment protects public university professors’ academic freedom; in 1967, the majority found that academic freedom is “a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.”

But Sanders’s post focused on his own employer’s seeming complicity, along with Purdue’s, in the argument that public university professors lack academic freedom in the classroom. Sanders pointed out that lawyers for Indiana and Purdue universities, the defendants in the ongoing case, had written in a one-paragraph filing that “in the interests of judicial economy … the university defendants embrace, incorporate by reference and join in” two documents that the attorney general filed. One was the brief arguing public university professors’ speech is government speech.

On Monday, however, the universities filed a note of clarification with the court saying they were not joining with the attorney general on that argument. IU spokespeople didn’t answer Inside Higher Ed’s follow-up questions about whether the lawyers filed this clarification due to Sanders’s post. A Purdue spokesman said “posts by Steve Sanders are in error on many fronts and misrepresent Purdue’s position in this litigation,” but didn’t specify what the errors were. Sanders, for his part, told Inside Higher Ed the universities’ clarification is “a good development that I’m sort of happy to take credit for.”

While the universities are distancing themselves from the attorney general’s arguments, attorneys in and outside of the Indiana case say court precedent cuts against the argument Rokita is making.

Precedent

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling that curtailed public employees’ free speech. In a case called Garcetti v. Ceballos, the majority ruled that “when public employees make statements pursuant to their official duties, the employees are not speaking as citizens for First Amendment purposes, and the Constitution does not insulate their communications from employer discipline.”

While the case didn’t deal with an educator, but with a Los Angeles deputy district attorney who alleged he was retaliated against for his speech, it raised a question about what seemed to be a settled legal matter: Do professors have First Amendment rights in public classrooms? It was a question the Supreme Court majority in Garcetti didn’t get into.

Justice David Souter, in a dissent joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and John Paul Stevens, wrote that “I have to hope that today’s majority does not mean to imperil First Amendment protection of academic freedom in public colleges and universities.” Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the court’s majority, responded to that dissent, saying it wasn’t deciding in the Garcetti ruling “whether the analysis we conduct today would apply in the same manner to a case involving speech related to scholarship or teaching.”

(Nonetheless, Rokita’s office wrote in its brief that “any speech pursuant to the teacher’s ‘official duties’ and ‘professional responsibilities’ is subject to state direction,” and it cited Garcetti to back this up.)

Souter’s hope seems to have stayed alive, at least so far. Greg Harold Greubel, a senior attorney for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a free-speech advocacy group, said that since the Garcetti case, every federal circuit court that has taken up the question of whether the First Amendment protects speech in public universities related to teaching or scholarship has found the same: Yes, it does. That includes judges in the Second, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Ninth circuits, Greubel said.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California at Berkeley School of Law, wrote in an email that “the law is uncertain here.” he Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit “expressly rejected the argument made by the Indiana and Florida attorney generals” a decade ago, he said. Still, Chemerinsky said, it’s “unknown what the Supreme Court will do. But there are Supreme Court cases expressly protecting academic freedom under the First Amendment and this would be inconsistent with that.”

But, with state legislatures pushing bills “intruding upon how professors teach certain things,” Greubel said he thinks lawyers will continue to make the argument—as attorneys representing both the states of Florida and Indiana have done—that public university professors’ speech is government speech. “I do feel that it will continue until it’s either taken up by the Supreme Court and they settle this, or every circuit court decides it,” he said.

In the 11th Circuit, Greubel himself is representing some of the plaintiffs in the Florida lawsuit that’s trying to permanently stop the Stop WOKE Act. That 2022 law—passed by Florida Republican lawmakers and signed by governor Ron DeSantis—limits the way public university faculty members can teach about race and gender. Florida students and faculty members have so far won and maintained a preliminary injunction that’s blocking the act from impacting the state’s universities.

Oral arguments in June made clear the act’s possible impact if they lose. An appeals court judge asked an attorney representing Florida, “Could a legislature prohibit professors from saying anything negative about a current gubernatorial administration?” The lawyer replied, “I think, your honor, yes, because in the classroom the professor’s speech is the government’s speech and the government can restrict professors.”

If such arguments prevail, Greubel said, “it would magically turn [professors] from experts in their own fields to mouthpieces of the state.” He said “there’s no place that it would ever stop, really.”

Stevie Pactor, a staff attorney for the ACLU of Indiana, said that if professors’ speech really is considered government speech, there “just is no such thing as academic freedom.” Turning a professor into a “parrot” of the state, she said, “subverts the entire role” of a university.

Attorney General Rokita didn’t provide an interview for this article, but his office sent a statement. “The manufactured fears put forth in yet another illegit lawsuit by the ACLU don’t lack imagination, but the professors do lack standing to even bring this action. Our office will continue to defend in court this new law, which enables students to engage in free inquiry and ensures state universities foster diversity of thought.”

Sanders, the law professor, wrote in his Medium piece that “no Supreme Court decision has endorsed the government-spokesperson view of professors in the classroom, and numerous lower courts have rejected it.” He said the argument, “taken to its logical conclusion,” would reduce professors to “ventriloquist dummies for whatever political faction happens to wield power on a university board of trustees or in the Statehouse.”