You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

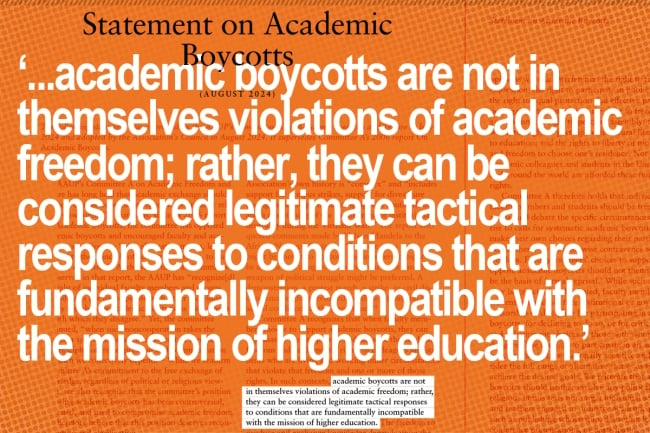

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | American Association of University Professors

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) has dropped its nearly 20-year-old categorical opposition to academic boycotts, in which scholars and scholarly groups refuse to work or associate with targeted universities. The reversal, just like the earlier statement, comes amid war between Israelis and Palestinians.

In 2005, near the end of the second intifada, a Palestinian uprising, the AAUP denounced such boycotts; the following year, it said they “strike directly at the free exchange of ideas.” That statement has now been replaced by one saying boycotts “can be considered legitimate tactical responses to conditions that are fundamentally incompatible with the mission of higher education.” The new statement doesn’t mention Israel, Palestine or other current events—but the timing isn’t coincidental.

The new position says that “when faculty members choose to support academic boycotts, they can legitimately seek to protect and advance the academic freedom and fundamental rights of colleagues and students who are living and working under circumstances that violate that freedom and one or more of those rights.”

The AAUP is both a union and a national faculty group that establishes widely adopted policies defining and safeguarding academic freedom and tenure. Its Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure voted to approve the new stance in July, and the group’s national Council voted to approve it Friday.

The old policy had “been reportedly used to squelch academic freedom,” said Rana Jaleel, chair of Committee A. Now, “what we’re saying is that we trust our members—our faculty on the ground who are doing the organizing work—to assess, weigh and decide whether or not they want to participate in academic boycotts,” she said.

The AAUP’s new statement still says boycotts shouldn’t “involve any political or religious litmus tests nor target individual scholars and teachers engaged in ordinary academic practices,” such as conference presentations. It says such “boycotts should target only institutions of higher education that themselves violate academic freedom or the fundamental rights upon which academic freedom depends.”

“Freedom to produce and exchange knowledge depends upon the guarantee of other basic freedoms,” the document says—including, among others, the freedom to live, the freedom from arbitrary arrest and the freedom of movement.

Both two decades ago and today, the organization’s statements on academic boycotts have come amid calls from Palestinian supporters to boycott Israel—academically, economically and otherwise. Despite the AAUP’s past opposition, some major discipline-based U.S. scholarly associations have endorsed academic boycotts of Israel: the American Studies Association did so around a decade ago, and the American Anthropological Association joined last year.

The AAUP, while it called for an "immediate ceasefire” in Gaza in February and has now dropped its opposition to academic boycotts, hasn’t gone as far as specifically endorsing an academic boycott of Israeli universities or the broader boycott, divestment and sanctions movement.

While Jaleel said this policy change is being made in the context of Israel and Gaza, she said it is “not advocating for academic boycotts, it’s not advocating for any particular form of academic boycott that’s going on now, it’s just saying that, as a tactic, it doesn’t necessarily violate academic freedom.” She said AAUP’s Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure isn’t considering going further and calling for an academic boycott of Israeli universities, but other arms of the AAUP could now push for the organization as a whole to take that stand.

A look back on the AAUP’s now-abandoned statement opposing academic boycotts shows how the organization found it necessary, from the beginning, to thread the needle on what kinds of protests it deemed acceptable.

‘Extraordinary Situations’

In 2005, the British Association of University Teachers announced a boycott of Israel’s Bar-Ilan and Haifa universities. In response, the AAUP released a two-paragraph objection.

“We reject proposals that curtail the freedom of teachers and researchers to engage in work with academic colleagues, and we reaffirm the paramount importance of the freest possible international movement of scholars and ideas,” the statement said. The British group quickly dropped the academic boycott, but the AAUP remained opposed to this tactic. The following year, it explained itself.

“We have been urged to give fuller consideration to the broad and unconditional nature of our condemnation of academic boycotts,” wrote the authors of “On Academic Boycotts,” a four-page report that explains the AAUP’s position. The authors—a Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure subcommittee—appeared to wrestle with contradictions.

“Are there extraordinary situations in which extraordinary actions are necessary, and, if so, how does one recognize them?” they asked. “How should supporters of academic freedom have treated German universities under the Nazis? Should scholarly exchange have been encouraged with Hitler’s collaborators in those universities?”

Ultimately, though, they came down—on the AAUP’s behalf—against academic boycotts altogether. “We resist the argument that extraordinary circumstances should be the basis for limiting our fundamental commitment to the free exchange of ideas and their free expression,” they wrote.

The now-superseded statement noted that “legitimate protest against violations of academic freedom might, of course, entail action that could be construed as contradicting our principled defense of academic freedom.” The writers acknowledged, for instance, that the AAUP has long censured institutions' administrators for not observing its academic freedom and tenure principles.

The AAUP’s “censure” list currently includes 60 institutions or systems. One of the 60 is the entire State University System of New York, and another is the whole University System of Georgia. But the authors of the 2006 statement wrote that these censures differ from boycotts in which scholarly groups disassociate with a targeted university. The AAUP “engages in no formal effort to discourage faculty from working at these institutions or to ostracize the institution and its members from academic exchanges," they said.

The AAUP—which also recommends policies for the shared governance of colleges and universities among their faculty, administrators and boards—also keeps a separate “sanction” list of institutions that it says have seriously departed from its favored governance standards. Fourteen institutions are currently on that list, which, like the censure list, is basically a form of public shaming, just for a different transgression.

Further, AAUP campus chapters that are certified as local unions sometimes go on strike. The old statement’s authors acknowledged that strikes often involve the local union asking speakers not to come to campus, and involve faculty members from other institutions refusing to attend on-campus conferences. “While the AAUP insists on action that conforms to its principles, practical issues sometimes produce dilemmas that must be addressed,” they wrote.

The AAUP, while it has been denouncing academic boycotts for two decades, did once endorse an economic boycott: In the 1980s, it supported the movement to divest from South Africa over its policy of apartheid. But the authors wrote that the AAUP’s “resolutions did not apply to exchanges among faculty.”

They ultimately came down against academic boycotts, noting that not all scholars in a country are necessarily complicit with state actions, and that a boycott could harm professors with ideas “that could contribute to changing state policy.”

The old statement even included a specific criticism of using an academic boycott to protest Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. “The academic boycott seems a weak or even a dangerous tool,” they wrote. “It undermines exactly the freedoms one wants to defend, and it takes aim at the wrong target.”

But historian Joan Wallach Scott, one of the authors of the old statement, abandoned her opposition to academic boycotts a decade ago. In fact, she has called for one against Israeli universities. “The boycott is a strategic way of exposing the unprincipled and undemocratic behavior of Israeli state institutions; its aim might be characterized as ‘saving Israel from itself,’” she wrote in the AAUP’s Journal of Academic Freedom in 2013. She said that “paradoxically, it is because we believe so strongly in principles of academic freedom that a strategic boycott of the state that so abuses it makes sense right now.”