You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of California Board of Regents debated this week whether to limit departments from making statements on their landing pages on university websites.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | TheLetter/Wikimedia Commons | MFASTILY/Wikimedia Commons

University of California professors and board members are divided over a controversial proposal to ban departments and campus centers from making statements containing their “personal or collective opinions” via “official channels of communication.” Those include “the main landing pages” of individual schools, departments, centers and other campus entities. The policy would not prevent the system president, chancellors or regents from using university websites to make statements on political or social issues.

The proposal, discussed during a long and heated Board of Regents meeting Wednesday, was tabled Thursday until the next meeting in March.

It comes amid impassioned debates about the Israel-Hamas war on campuses in the UC system and across the country. Arguments about when, where and what members of the university community can say about the war have convulsed institutions from Harvard to Indiana University at Bloomington. But departmental websites have proven a particularly contentious forum for addressing the conflict. While some faculty members say that preventing them from using such sites to discuss global events violates academic freedom, supporters of such bans argue that it’s easy to misconstrue a statement on a department website as representing the entire institution—or all the members of the department.

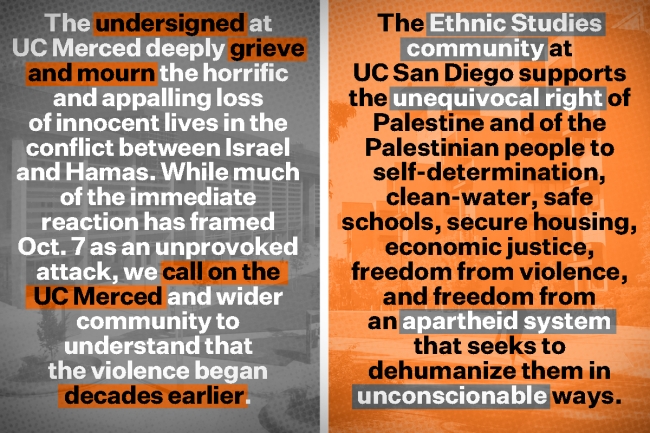

Multiple departments within the UC system have commented on the ongoing war. At UC Merced, for instance, the Department of History and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies issued a statement after the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel mourning “the horrific and appalling loss of innocent lives in the conflict between Israel and Hamas.” The statement also noted that much of the immediate reaction framed the attack as “unprovoked” and called on the community “to understand that the violence began decades earlier.” Along similar lines, the ethnic studies department at UC San Diego noted on the Statements and Commentaries page of its site that the department “supports the unequivocal right of Palestine and of the Palestinian people to self-determination.”

Ahead of Wednesday’s Board of Regents meeting, some UC faculty members raised concerns that the proposal was overly broad and risked limiting free speech. In response, the board considered two different proposals at the meeting: one that would give university officials broad discretion over statements on university websites, and one that would only prohibit opinionated statements on department landing pages.

The regents focused their discussion on the second option, debating for almost an hour whether it was sufficiently clear and if it might hinder faculty speech.

“I think this limitation could impede the dissemination of vital information on issues to the public, hindering the university’s role of contributing to informed discourse of societal awareness,” said Josiah Beharry, the student regent-designate, during the meeting.

“Faculty can have their Twitter accounts, they can do social media, they can publish peer studies. There are so many other ways,” countered Regent Jonathan Sures. “This policy was thoughtfully designed to protect the academic freedom and the free speech of everybody and to give certain designees the right to put official communications out on behalf of the University of California.”

System leaders have faced external and internal pressures to clamp down on statements made by professors regarding the ongoing Israel-Hamas war.

Sures wrote a scathing letter to the UC Ethnic Studies Council, a group of ethnic studies professors from across the system, in October after the council made a public statement accusing system leaders of anti-Palestinian bias. Sures called the statement “appalling and repugnant” and urged the council to take it down. The council refused and called for Sures’s resignation.

The issue of whether faculty should be allowed to post political statements specifically on departmental sites is a relatively unexplored one—though many campuses have wrestled with the broader question of whether departments should take a stance on political events. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for one, published guidance in late 2022 discouraging departments from commenting on “state, national, or international policy matters.” Any statements that are made, it said, should be attributed to specific individuals, and faculty members with opposing perspectives should be given the chance to express their opinions in the same forum.

Anita Levy, senior program officer in the American Association of University Professors’ academic freedom, tenure and governance department, said that the association has no formal guidance on political speech on departmental websites. It does, however, have a policy entitled “Academic Freedom and Electronic Communications,” which states that in almost every situation, “academic freedom, free inquiry, and freedom of expression within the academic community may be limited to no greater extent in electronic format than they are in print.”

Opposition and Support

Before Wednesday’s meeting, the UC Ethnic Studies Council made a post on Instagram decrying the proposal as “censorship” and encouraging people to attend the meeting and voice their opposition in public comments.

“This sweeping statement could limit everyone’s ability to speak out on any significant moment or injustice,” the post read, “i.e. No statements on PRIDE, heritage, school-wide tragedies/issues … However, the Regents, President, and Chancellors are still allowed to put out statements claiming to speak for the entire body of the university, erasing the voice of the true collective and any demands from faculty and students.”

Some professors, however, approve of limiting statements related to Israel on department sites because of concerns about antisemitic messaging. A group of about 400 current and emeritus faculty members signed a letter to the board Monday asking it to rein in faculty members using university “resources” for “political advocacy or indoctrination” related to anti-Zionism.

“Of particular concern is the role played by individual faculty members and whole departments in fomenting the hostile, antisemitic climate that exists on many of our campuses, through their use of the University’s name, facilities and resources to engage in anti-Zionist political expression, whose goal is to demonize, delegitimize, and ultimately dismantle the Jewish state,” the letter reads.

New Policies at Barnard

The UC situation mirrors an ongoing controversy at Barnard College, a women’s college that is part of Columbia University. There, in late October, the Department of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies shared a statement on its homepage expressing support for Palestinian students and posted links to resources and articles on the conflict, including research on the subject by Neferti Tadiar, a professor in the department.

Administrators promptly took the statement down on the grounds that it constituted “political speech,” The New York Times reported Tuesday. It was replaced with the statement that had previously occupied the same spot on the landing page: a declaration of support from the college’s Africana studies department for the Black Lives Matter protests that had taken place in 2020.

Since then, Barnard has added a policy that was shared with faculty via email on Nov. 6 that requires departments to run by administrators any changes they want to post to their websites. In a statement emailed to Inside Higher Ed, a Barnard spokesperson explained that under the new approval process, “the provost reviews proposed departmental website edits for editorial integrity and academic relevance.”

The college also expanded its definition of political statements—which are barred from both barnard.edu websites and signs on campus—to include “all written communications that comment on specific actions, statements, or positions taken by public officials or governmental bodies at local, state, federal, and international levels; attempt to influence legislation; or otherwise advocate for an outcome related to actions by legislative, executive, judicial, or administrative bodies at local, state, federal, and international levels.”

The policy changes were designed to ensure that statements posted on a department’s website could not be misconstrued as the college’s official stance, the university spokesperson wrote. The institution also wanted to avoid “marginalizing those who disagree” with their department’s statements.

“Even if such statements come with disclaimers, they can be perceived as creating a litmus test for students or faculty wishing to participate in the department’s courses and other activities. We oppose such litmus tests,” the spokesperson wrote. “We instead strive to foster robust debate and inquiry from multiple perspectives in a learning environment where everyone feels like they can speak and be heard with respect and empathy.”

Both campus constituents and outside activists have pushed back on the new rules. The New York branch of the American Civil Liberties Union argued in a six-page letter to Barnard president Laura Rosenbury that they violate academic freedom. Notably, the NYCLU claimed that professors’ right to academic freedom extends to their departmental websites, “which perform important pedagogical functions and provide significant opportunities for scholarly discourse.”

Janet Jakobsen, a faculty member in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, said in an interview with Inside Higher Ed that posting scholarly works—which are often overtly political—to the university’s website is well within faculty members’ scholarly duties.

“Part of scholarship is not just producing it and offering it in a scholarly venue; it’s offering it to the public,” she said. “The public doesn’t have to agree, but one of the reasons academic freedom exists is because supposedly this is an institution where knowledge that is not necessarily beholden to particular interests is produced.”

After the new policies were implemented, the women’s studies department submitted a request for changes to its website: the addition of a link to a newly created website where faculty members would post the resources that had been taken down in October, as well as two works by Tadiar, “Why the Question of Palestine Is a Feminist Concern” and “Powers of Defending Freedom.” On Jan. 23, two months after the initial request was made, the links to Tadiar’s work went live, but the link to the external website has not been added.

Jakobsen said the delay exemplifies why the college’s actions are dangerous.

“We try to respond for our students in the moment, and because of prior restraint we’re responding months later,” she said, noting that administrators had told some faculty members that the review process was only supposed to take 24 hours. “If it’s controversial, it’s going to take this kind of time.”

Protecting or Curtailing Free Speech?

Tammi Rossman-Benjamin, founder of the AMCHA Initiative, an organization that combats campus antisemitism and the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement against Israel, argued that a university’s public image and reputation can be impacted by departments posting polarizing statements.

She agrees with the UC system’s proposed policy on the matter—even though, as written, it could also ban statements she agrees with, such as a Jewish studies program posting “We stand with Israel” on its site.

“It’s treating one symptom of a much bigger problem. Is it a good first step? I think it’s a good first step,” she said, adding that it sends a message that “there are people who are watching them and holding them accountable for what they put up on official university channels.”

But others, including Mary Rose Kubal, a political science professor at St. Bonaventure University and the president of New York’s AAUP chapter, see policies like Barnard’s and the one proposed for the UC system as another worrying sign of university interference by donors, politicians, alumni and the public.

“I don’t think the Barnard administration would have taken these steps if they hadn’t been pressured by actors outside of the community … These are academic articles,” Kubal said, referring to the links shared by the Barnard women’s, gender and sexuality studies department in October. “How are we going to have an informed, civil discussion if we’re not providing access?”

She also questioned why only statements in support of Palestinian students and Gazans have received so much pushback, even though it’s relatively common for departments to post about a range of political issues on their websites. Even now, Barnard’s women’s, gender and sexuality studies website contains an image that reads, “smash the white suprema-cis(t) hetero-patriarchy.”

But she empathized with administrators who are currently dealing with the choice between cowing to outside forces or losing their jobs.

“I think the administration at Barnard is under a lot of pressure, as are administrations at a lot of institutions, and they seem to be caving,” she said. “Higher education is a really hard place to be right now—even as students, but certainly as administrators. I don’t envy the administrators of Barnard and Harvard and MIT.”

Laura Beltz, director of policy reform at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a free speech advocacy organization, said she generally believes in “institutional neutrality” to prevent dissenting voices from feeling ostracized, but she finds the language of the UC system’s original proposal unclear and concerning.

“It does have the potential to chill faculty speech due to how it’s written,” she said. “It’s very vague and ambiguous … We’re concerned that faculty may see this policy and feel that they, as individuals, shouldn’t speak out on matters of public concern.”

She also noted that faculty members have a right to group together and make collective statements.

‘Serious Concerns’ About Procedure

Some UC professors criticized not just the proposal but also the lack of faculty input in drafting it. James Steintrager, chair of the system’s Academic Council, wrote a letter to system president Dr. Michael V. Drake ahead of the meeting expressing “serious concerns” that the policy didn’t undergo a systemwide review process with input from the Academic Senate, as such proposals usually do.

“We are deeply concerned that the process circumvented normal shared governance protocols for a policy that will significantly affect faculty across the University,” he said in the letter.

The former chairs of the University Committee on Academic Freedom raised similar concerns in a letter to the board. Ty Alper, clinical professor of law at UC Berkeley, and Brian Soucek, law professor and chancellor’s fellow at UC Davis, argued that the proposal’s addition to the agenda was “sudden, opaque, and seemingly devoid of any collaboration at all with the faculty, departments, schools, and other units that it would affect.”

“There are some departments within the university that see this sort of thing as really central to their departmental mission, that speaking out on issues that they see as falling within their expertise is very much part of their self-definition as a department,” Soucek told Inside Higher Ed.

He noted that the committee already created a set of recommendations, approved by the Academic Council, regarding political statements by departments, in 2022. The recommendations were in response to controversy over another Israel-Hamas conflagration, when multiple gender studies departments signed on to a pro-Palestinian statement by the Palestinian Feminist Collective. The recommendations allowed such statements on university websites but offered a set of guidelines for them.

Unlike the stalled proposal, that policy “went through systemwide review at all levels at all 10 campuses,” Soucek said. For the recent proposal, “none of that happened.”

He added that while statements on the Israel-Hamas war are garnering attention right now, university departments and centers make all kinds of statements on political and social issues, ranging from commemorative posts about Sept. 11 to commentary on events such as the Jan. 6 uprising.

“The question is, is there any good reason for that: to allow the university as a whole to speak, but not to hear from what disciplinary experts within a given field think about issues, hopefully issues that they have some expertise in?” he said.