You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

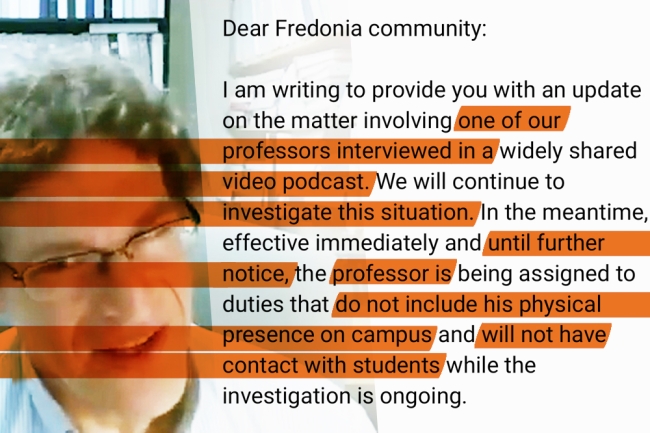

SUNY Fredonia's president clarified the conditions of Kershnar's prohibition from campus in a letter shortly following the release of the professor's controversial podcast comments.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | YouTube | SUNY Fredonia

A year and a half after Stephen Kershnar, a polarizing philosophy professor at SUNY Fredonia, was barred from the campus and relegated to teaching online courses, university officials are still intent on keeping him out.

The university’s lawyer argued last Friday during a federal district court hearing on a lawsuit filed by Kershnar against the State University of New York at Fredonia president and provost that Kershnar’s controversial past comments about pedophilia—which included his questioning whether “adult-child sex” is always wrong—make it impossible for him to return to campus without posing a risk to students and faculty and staff. The lawyer cited threats of violence by those who oppose Kershnar’s return and accusations that the small, public institution in western New York is “an advocate to child sexual exploitation.”

Kershnar’s lawyers argued that the university’s order—which prohibits the professor from entering the campus and having contact with any students, faculty or staff— is a violation of his First Amendment rights.

Assistant Attorney General Jennifer Metzger Kimura, who is representing the university’s president, Stephen Kolison Jr., and the provost, said SUNY Fredonia’s decision to remove the professor was not made because of his comments but in response to the egregious emails and social media commentary that resulted from his comments.

“President Kolison’s aim in distancing SUNY Fredonia from this lightning rod position was to protect the campus community in the wake of the storm,” Kimura wrote in a court filing.

Despite acknowledging that the posts and emails have declined in volume and do not include “direct threats,” Kimura argued that the looming risk of attack if Kershnar were to return is enough to justify the university’s decision.

Kimura did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Adam Steinbaugh, a lawyer with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression who is representing Kershnar, argued that nonexplicit threats shouldn’t be enough to keep the professor off campus.

“If the complaints or harassing emails of a few people, or even a good number of people, is enough to silence any faculty member at a public university, then higher education is in dangerous territory,” Steinbaugh said in an interview. “The First Amendment doesn’t tolerate a heckler’s veto.”

U.S. District Court Judge Lawrence Vilardo, who was hearing the case, did not issue a ruling on Friday. However, according to The Buffalo News, he did express concern that the university’s rationale could lead to the limitation of the free speech rights of any professor if enough people opposed comments made by the professor.

“I think your argument leads to frightening possibilities on college campuses,” Vilardo told The Buffalo News.

Steinbaugh anticipates Vilardo will rule on the case within the next few weeks.

A ‘Taboo’ Podcast

Kershnar, a distinguished teaching professor, had long studied controversial issues. However, he made the statement now under scrutiny during an interview about “sexual taboos” on the philosophy podcast Brain in a Vat in late January 2022.

“Imagine that an adult male wants to have sex with a 12-year-old girl. Imagine that she’s a willing participant,” Kershnar said on the podcast. “It’s with a very standard, very widely held view that there’s something deeply wrong about this. And it’s wrong independent of it being criminalized. It’s not obvious to me that this is, in fact, wrong. I think this is a mistake. And I think that exploring why it’s a mistake will tell us not only things about adult child sex and statutory rape, but also about fundamental principles of morality.”

That statement was subsequently highlighted on Libs of TikTok, a politically conservative social media account which tagged President Kolison Jr., and posted on X, formerly known as Twitter: “Hi @DrKolison, it appears you have a problem at your university.”

The posting was quickly promulgated across social media. Two days later, Kershnar was barred from coming to campus until further notice.

‘Hunters Don’t Howl’

Brent Isaacson, a former FBI agent who specialized in behavior analysis and was police chief at SUNY Fredonia until June 30, said the university made the right call.

“I know from extensive training … that targeted violence against individuals and institutions starts with deeply held grievances,” Isaacson wrote in a threat assessment which he submitted to the university’s leaders days after Kershnar’s comments were released. “I also know that there is a massive population of Americans who were either victims of child sexual exploitation in their youth or who have their own children who were victimized by others.”

“This situation has, in effect, given potential offenders a target upon which to focus their grievances against those who sexually exploit children,” he added.

Isaacson indicated in a court document filed in July that the university potentially faces such a threat because of the controversy over Kershnar. “I do not believe it possible to adequately protect the SUNY Fredonia campus in a situation where Kershnar is physically present on the campus or having authorized contacts with SUNY Fredonia students,” Isaacson wrote.

Isaacson said it was a “cold comfort” that the emails and online comments about Kershnar have not directly threatened to harm the campus.

“Many laypersons, without training or experience in threat assessments, view explicit and articulated threats as the most credible and serious,” he wrote. “In fact, they rarely are. We often say in threat assessments, ‘hunters don’t howl, and howlers don’t hunt.’ Accordingly, my concern is directed to the much larger audience who have remained silent.”

‘He Belongs in a Classroom’

But Keith Whittington, a representative of the Academic Freedom Alliance and the William Nelson Cromwell professor of politics at Princeton University, said in an interview that he doesn’t buy such an “extraordinarily sweeping” rationale and that he would be “surprised if the court were to uphold the university’s actions.”

Whittington said SUNY Ferdonia administrators were empowering people who disagreed with Kershnar’s comments to essentially gag him “and effectively suppress anyone else who might be interested in making similar kinds of arguments.”

“Really, it just seems pretty outrageous that he continues to be banned from being on campus,” Whittington said.

Whittington said he understands the university’s concerns about campus safety—especially at a time when campus shootings have become more common—but those concerns should not undermine academic freedom.

“Here, the university wants to say, ‘Well, precisely because we don’t have any specific or credible threats, we have to take dramatic action,’” he said. “Once you say that, now we just have a completely evidence-free world in which university officials don’t need to point to anything at all.”

At the time of the podcasts’ release, a student-led petition with some 14,000 signatures called on Fredonia to take further action and fire Kershnar.

While both students and the university’s legal team have voiced concerns that student interactions with Kershnar could result in sexual harassment, Steinbaugh, Kershnar’s lawyer, said those concerns were unrealistic.

The fact “that a philosophy professor engages in the exchange of ideas and hypotheticals does not mean that he’s doing that out of personal interest. He is paid and he is hired to engage in the evaluation of society’s moral questions,” Steinbaugh said. “He belongs in a classroom. That’s what he’s been praised for for years, and I think that that is what he has a First Amendment right to continue doing.”