You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

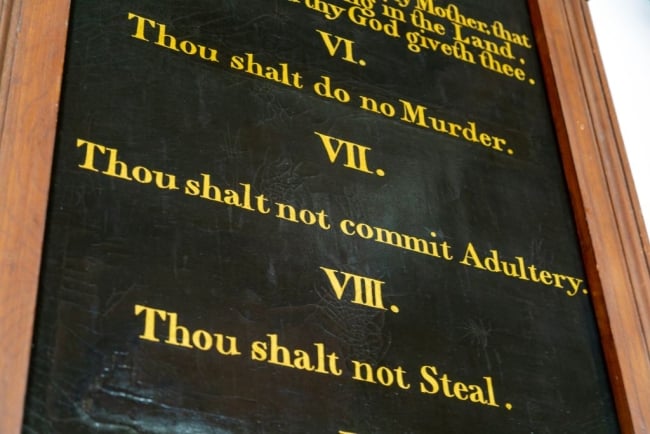

The text of the Ten Commandments will be hung in every Louisiana public school classroom starting in January, pending litigation.

Geography Photos/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A new Louisiana law that mandates a poster-sized copy of the Bible’s Ten Commandments be hung in every public school classroom—including at colleges and universities—has already been challenged by nine Louisiana families, whose lawyers say they hope a judge will grant a preliminary injunction before the 2024–25 academic year starts.

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, Daniel Mach, director of the ACLU Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief, called the law “an egregious violation of religious liberty; the school officials can’t force religious scripture on students as a condition of getting a public education. It’s unfair and it’s unconstitutional.”

The Louisiana law is just one of several recent moves by conservative politicians and education leaders to insert Christian teachings into public education; just this year, Oklahoma’s superintendent of schools ordered public schools to teach about the Bible and Texas unveiled a new elementary school curriculum that includes biblical stories and scenes. In both cases, education leaders argued that references to the Christian Bible are so pervasive in culture and literature that students benefit from learning about them.

Meanwhile, the lead sponsor of the Louisiana bill, HB 71, said during a debate over the legislation that her aim was to “have a display of God’s law in the classroom for children to see what He says is right and what He says is wrong,” according to the lawsuit filed against it.

Higher education has mostly been spared from state efforts to infuse public schools with religious teachings, but Louisiana’s law includes all 32 public colleges, universities and trade schools in the state—even as most of the rhetoric surrounding the bill seems to focus on young children and how and what they should be taught about morals and religion.

None of the state’s four higher education systems responded to Inside Higher Ed’s request for comment on whether and how they are preparing to implement HB 71, which gives institutions until Jan. 1, 2025, to post the Scriptures.

40-Year Precedent

Mach said he is confident that the lawsuit, brought by the ACLU and three other organizations representing the plaintiffs, will be successful. But experts say many factors could contribute to whether the law will ultimately be allowed to go into effect.

A 1980 Supreme Court ruling, Stone v. Graham, struck down a nearly identical law in Kentucky, finding that there was no secular purpose for displaying the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. The Louisiana law attempts to circumvent that ruling by requiring institutions to display the Ten Commandments alongside a context statement that provides information about their history in public education, citing early textbooks that included them.

Republican lawmakers have defended the bill in the media on those grounds.

“Although this is a religious document, this document is also posted in over 180 places, including the Supreme Court of the United States of America. I would say [it] is based on the laws that this country was founded on,” Republican state senator Adam Bass told KALB, a local television station in Baton Rouge.

Ira C. Lupu, the F. Elwood and Eleanor Davis Professor Emeritus of Law at George Washington University, said the case will likely rest on that distinction.

“That’s what the argument is going to look like—does this have a secular purpose because it’s grounded in a broader view of culture and history? Or is that just pretext?” he said in an interview with Inside Higher Ed.

He noted that while the law outlines other historical documents that “[affirm] the link between civil society and God”—such as the Mayflower Compact of 1620—it does not mandate that those documents also be displayed.

James W. Fraser, professor of history and education at New York University and the author of Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), said the connection between the Ten Commandments and American public schools is thin at best.

“There’s very little evidence that the Ten Commandments, as such, were in schools any time after the Civil War, which was a rather long time ago. My basic analysis of that history is that it’s nonsense,” he said. Within higher education, “I know of no example—even of religious colleges, even before the 19th century—where the Ten Commandments were posted. It may have happened, but it was not the norm.”

Impact on Higher Education

Even if the courts take into consideration the precedent set by Stone v. Graham, there is a slight chance that it wouldn’t apply to higher education, since the Kentucky law only included K-12 schools. A court could choose to uphold the law only for postsecondary institutions while striking it down for K-12, Lupu said. Moreover, concerns about whether the document would count as forcing students into a certain belief system, which is unlawful under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, would be significantly reduced among college students.

“At postsecondary, the likelihood that you’re going to be coerced into believing the Ten Commandments is God’s truth and God’s law is even less than for children,” Lupu said.

An unintended consequence of the law, if enacted at colleges and universities, might be that professors would have the academic freedom to discuss and critique the Ten Commandments and the classroom signage with their students, Lupu noted.

A philosophy professor, for example, could stand in front of his class and say, “‘I think the idea that God commanded those things are bunk … there is no god and I’m going to give an argument.’ That would absolutely be an exercise in academic freedom,” he said.

Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, another organization representing the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against HB 71, said she is not worried that the courts will separate K-12 and higher education in evaluating the constitutionality of the law.

Though the Supreme Court has been particularly militant about protecting the religious freedom of school-aged children and their families, applying the law to colleges would violate other religious freedoms, she said. For one thing, it would signal the government’s preference for one religion over others, putting taxpayers’ money toward a faith that isn’t necessarily their own (though the law does note that schools that don’t want to pay for the displays themselves can accept donated funds or signs).

Fraser, who is also the pastor emeritus at Grace Church in Massachusetts, agreed that the law is unlikely to be enacted.

“This is clearly just performance legislation,” he said. “I don’t think it’s meant to accomplish some kind of change; it’s meant to make the politicians look popular. Of course, I’m really deeply offended by it both as a historian and as a religious leader. The United States has thrived on a separation of church and state.”