You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Numerous institutions are nearing a sticker price of $100,000.

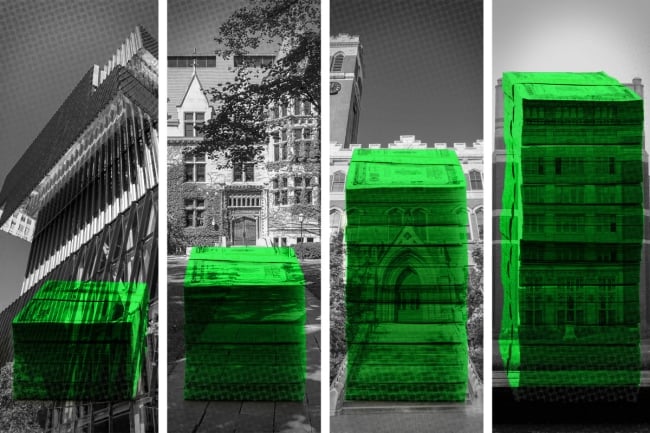

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | APCortizasJr, SeanPavonePhoto/iStock/Getty Images | Nicomachian, Jared and Corin/Wikimedia Commons

For years, headlines have warned that the cost of attending college would eventually exceed $100,000-a-year at some institutions.

Law schools at Columbia and Stanford Universities and the University of Chicago crossed that threshold in 2019; some higher ed experts predicted that the most expensive private four-year institutions would join them by 2030.

Now that barrier could be broken as early as next year, some believe.

Following a sharp inflationary period in 2022 and rising operating costs for institutions across the U.S., the race to a $400,000 college education is heating up fast. And Vanderbilt University may have taken the lead, with total costs for some undergraduates now estimated at more than $98,000 a year.

While the sticker price is a figure few students will pay, the number itself may have significant psychological and political implications for higher education amid the ballooning student debt crisis and mounting skepticism from lawmakers and the public about the value of a college degree.

Who Will Be Among the First?

Vanderbilt’s website puts undergraduate tuition and fees at $89,590. However, a recent cost of attendance estimate provided to a first-year engineering student—and published in Julian Treves’s CTAS Higher Ed Business newsletter—cites a sum of $98,426 for the 2024–25 academic year once certain fees are added, including a $1,700 “engineering laptop allowance.”

Treves, an investment adviser at Creative Financial Designs, said he was surprised by the cost estimate shared with him by an incoming Vanderbilt student. Given his work in tuition forecasting, he expected Vanderbilt’s price to be in the $91,000 range, “yet here it was almost at $99,000,” he said.

Treves expects Vanderbilt to cross the $100,000 mark next year, possibly becoming the first institution to do so. He believes other highly selective private institutions with sticker prices at or near the $90,000 mark—including Chicago, the University of Southern California, Washington University in St. Louis, Tufts University and a handful of others—won’t be far behind.

“My expectation is that many of the institutions, two years from now, will be above $100,000,” Treves said. “The fly in the ointment here is of course whether there’s massive resistance either from consumers or the administrators at colleges themselves to keep the price increases below the $100,000 mark just for optics reasons. But we don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Bryan Alexander, a senior scholar at Georgetown University, has written about institutions approaching the $100,000 sticker price since 2018. He initially suspected that Harvey Mudd College, Columbia University, the University of Chicago or Sarah Lawrence College might be the first to hit six figures, possibly by the 2029–2030 academic year. But Alexander has since noted that his outlook in 2018 “might have been too conservative”; in a 2023 update he projected that USC, Harvey Mudd, Chicago, Wellesley College, and the University of Pennsylvania would all reach $100,000 by the 2026–27 academic year. His estimates are based on the assumption of an annual 4 percent price increase at each college.

Alexander believes the $100,000 threshold is a culturally significant milestone.

“I think the psychological symbolism of going over six figures is big and I think it’s going to be a media storm when that happens because all kinds of people are going to get freaked out,” he said. “Conservatives who hate higher education will go nuts, but I think some progressives who think of higher ed as a bastion of wealth and privilege will also have negative reactions.”

Sandy Baum, a nonresident senior fellow at the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute, noted that some colleges have been moving toward the $100,000 figure for quite a while. Given rising operational costs and wage pressures for faculty and staff members, she said the $100,000 sticker price was “inevitable.” As the cost of providing an education increases, so does tuition.

“The norm keeps going up,” Baum said. “It’s hard to believe that it won’t keep going up.”

She stressed that most private colleges in the U.S. charge nowhere near $100,000. A recent tuition trends analysis from the College Board found that in the 2023–24 academic year, the average sticker price was $41,540 for private nonprofit four-year institutions, $29,150 for out-of-state students attending public universities and $11,260 for in-state students at public universities.

Treves noted that the colleges that can charge $100,000 per year are a rarity; most feature strong reputations, deep alumni networks and a “prestige factor” as part of the appeal.

And as sticker prices rise, another figure—one that gets less attention—will also likely go up: tuition discount rates. For the 2022–23 academic year, the average institutional tuition discount rate hit 56.2 percent for first-time, full-time freshmen, and 50.9 percent for all undergraduates, according to a National Association of College and University Business Officers study. That figure surpassed record highs reported by NACUBO in both 2022 and 2021.

Alexander expects the discount rate to climb as high as 75 percent at some institutions.

“The more unequal we get economically—and nothing seems to be slowing that down—I think we’ll likely see [sticker] prices continue to shoot up,” Alexander said, with discount rates climbing in tandem.

Unclear Pricing Models

Colleges themselves are quick to point out that few students pay full price.

Most institutions that Inside Higher Ed contacted for this story did not respond to requests for comment. Those that did emphasized their robust financial aid offerings.

“Last year, Vanderbilt spent $366 million on financial aid, with $244 million going to undergraduates, much of it supported by philanthropy. We provided the bulk of these funds through Opportunity Vanderbilt, our financial aid program that meets 100 percent of each admitted student’s demonstrated need without loans,” a Vanderbilt spokesperson said in a statement, which also noted that undergraduate tuition is covered for most students whose families earn under $150,000.

Even families earning more than that receive financial aid to attend Vanderbilt; the median financial aid award for students from families that earn between $150,000 and $175,000 is $62,650, according to the statement. And for families earning more than $200,000, the median annual award is $39,940.

Wellesley College also pointed to a high percentage of students receiving financial aid.

“Please note that most Wellesley students do not pay the total fee,” spokesperson Stacey Schmeidel said by email. “Nearly 60 percent of our students receive financial aid, and the average financial aid award is $67,469. We are committed to making a Wellesley education affordable and we meet the full calculated financial need for every student who enrolls.”

She noted that the $92,060 sticker price “reflects the increasing costs” of providing an education.

Thyra Briggs, vice president for admission and financial aid at Harvey Mudd, underscored that generous financial aid packages make the college more accessible—especially for those who would otherwise be unable to study there. She emphasized the importance of clear messaging and targeted outreach for low-income families to help them understand their options.

“For all of our low-income admitted students, we proactively waive their enrollment deposits and offer travel vouchers to fund a visit to campus,” Briggs said by email. “Once they are on campus, they are able to see what it means to be part of a small community in terms of close relationships with peers as well as with faculty and staff members. Every year we hear from families that with our generous financial aid, we are a less expensive option than many schools with a lower sticker price.”

A USC statement also highlighted its financial aid offerings.

“To support student access, USC fully meets demonstrated need,” officials said by email. “The undergraduate financial aid pool increases at least at the same rate as the tuition rate and is augmented to meet need as necessary.”

The statement also noted that the average annual growth rate for need-based grant support increased 11 percent between 2017 and 2023—almost triple the 4 percent annual tuition increase during the same period.

“The university expects to award more than a half-billion dollars in institutional aid to undergraduate students in the coming academic year,” the statement read.

Baum stressed that only a sliver of students will pay anywhere close to $100,000. She noted that the colleges charging such prices are notoriously difficult to get into; some have low single-digit acceptance rates. But even at those, most students get financial aid.

“I’m sure colleges and universities could do more to keep their costs down and so on, but it’s important to realize it’s not just that they're being greedy,” Baum said. “It’s very expensive to offer the kind of education that they offer. And that is not something that’s going to change and the fact that they discount for students who can’t afford to pay the full price, that’s a good thing.”

Treves estimated that at Vanderbilt, only about a third of students pay the full sticker price. The share is higher at Ivy League institutions, he said, but he still believes it’s around half.

Such pricing schemes are often a point of confusion and frustration for students and families. Studies have shown that students often don’t apply to colleges with high sticker prices—even though they may pay relatively little depending on financial aid packages and family income levels. However, Treves suggested there’s a recruiting payoff that makes the practice worthwhile for colleges.

“That sells better than simply reducing the cost of attendance to the actual market price and saying, ‘Hey, you got accepted,’ ” he said. “There’s a promotional and marketing value in sending out these big aid awards.”

Public Cost Concerns

But all the psychology and gamesmanship over pricing seems unlikely to improve the public’s perception of higher ed, even if most students pay less than advertised. If anything, it may energize critics, particularly once the $100,000 threshold is passed.

A Gallup poll last summer showed that American confidence in higher education had hit a record low. Only 36 percent of respondents reported “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education, down nearly 20 percentage points from almost a decade ago.

In February, Inside Higher Ed’s annual Survey of College and University Presidents found that most college leaders—66 percent of those who responded—were worried about waning public confidence in higher education. The top reason for public skepticism? Affordability, cited by 36 percent of respondents. And more than half the presidents (57 percent) said they believe the public’s cost concerns are valid.

As sticker prices climb, experts expect more backlash, even if the colleges charging the highest prices represent only a tiny fraction of U.S. higher education institutions. That may matter little to lawmakers, particularly in an election year when former president and GOP candidate Donald Trump has taken frequent aim at universities, though more often over politics than pricing. While such scrutiny may convince some colleges to hold off on raising prices to $100,000 this fall, Alexander said it’s only a matter of time. And when multiple institutions cross that threshold, he believes it will have an “an air of normalcy” about it.

“It's possible that we will simply accept that as the way things are,” he said.