You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

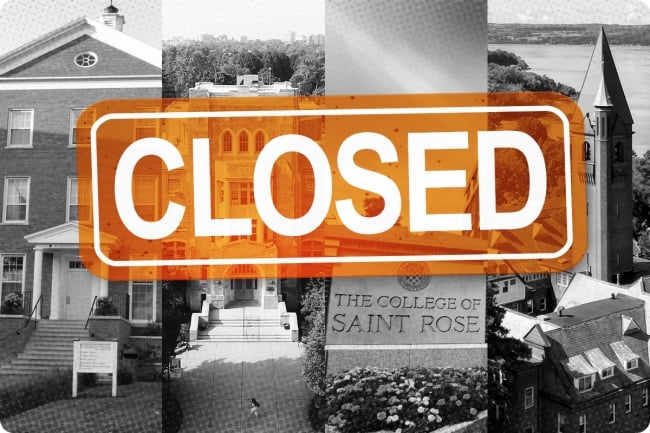

Cazenovia College, Medaille University, the College of Saint Rose, and Wells College are among the New York institutions that have announced closures since late 2022.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Idawriter/Wikimedia Commons | Medaille University | Michael P. Farrell/Albany Times Union via Getty Images | Wells College

After 156 years, Wells College in New York will close next month.

In announcing the closure Monday, college officials echoed the decision made by other struggling institutions across the nation, citing insufficient revenues for supporting “long-term financial stability” at Wells.

“As trustees, we have a fiduciary responsibility to the institution; we have determined after a thorough review that the College does not have adequate financial resources to continue,” board chair Marie Chapman Carroll and President Jonathan Gibralter wrote in an announcement posted on the college website Monday morning. “As you may be aware, many small colleges like Wells have faced enormous financial challenges. These challenges have been exacerbated by a global pandemic, a shrinking pool of undergraduate students nationwide, inflationary pressures, and an overall negative sentiment towards higher education.”

Wells officials did not respond to a request for further comment.

The closure, effective at the end of the spring semester, comes on the heels of a similar announcement by the University of Saint Katherine in California last week, which follows a string of others over the past year. Now, as 2024 marches on, college closures appear to be picking up pace.

Mounting Economic Pressures

In the closure announcement, officials noted that trustees have long looked for “creative solutions to raise revenues in hopes of avoiding closure,” including seeking a partnership to stay afloat. But those efforts did not pan out as hoped, prompting the decision to shutter the college.

For many in the Wells community, the news came as a shock. For New York’s higher education landscape, it marks another institution lost in a state that has been hard hit by closures.

On paper, Wells’s struggles appear evident.

The college enrolled 357 students in fall 2022, according to the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. That number has been falling steadily in recent years, from about 500 students in past years, a number it has not hit since 2016.

Public financial documents show that the private, liberal arts college lost money in five of the last 10 available fiscal years.

Founded as a women’s college in 1868, Wells went co-educational in 2005 in an effort to increase enrollment. The decision appeared to provide a short-term boost; in 2007, officials told Inside Higher Ed that the college had welcomed its largest incoming class since the 1970s. But the move ultimately failed to keep economic pressures at bay for long.

While the financial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were not mentioned specifically in the closure announcement, they, too, appear to have played a role. In 2020, President Gibralter warned that Wells could close due to the loss of student fees that came with shutting down campus during the pandemic. Gibralter noted at the time that Wells had a meager endowment, reportedly about $24 million, only 15 percent of which was unrestricted and accessible for general spending purposes.

The college managed to hang on for four more years.

Broader Trends

For New York, the Wells closure reinforces what has become a troubling trend among private, nonprofit, tuition-dependent institutions.

Last year the state saw Medaille University, Alliance University and the College of Saint Rose all announce closures. The King’s College effectively shut down without making a closure announcement. And in 2022, Cazenovia College announced it would close after defaulting on a $25 million bond payment.

The Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities, which represents more than 100 institutions in the state, did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

Elsewhere in the country, a handful of colleges have also recently announced plans to close.

Last week the University of Saint Katherine in California announced it was filing for bankruptcy and closing abruptly. It was preceded by Goddard College in Vermont, Oak Point University in Illinois, Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama, Fontbonne University in Missouri, and Notre Dame College in Ohio, all of which have announced plans to close this year. Similarly, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts announced in January it is ending its degree offerings.

For the most part, college closures are the result of some common factors: financial instability brought on by declining enrollment and compounded by rising operating costs.

Rachel Burns, a senior policy analyst for the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, noted that shrinking enrollment typically plays the biggest role.

“Enrollment declines (leading to financial challenges) are the largest driving factor for college closure,” Burns wrote via email. “The reasons for these declines are myriad—the ‘demographic cliff’ due to lower birthrates in the U.S., rising costs of higher education (and more public questioning of the value of higher education), and the state of the economy (i.e., more employment opportunities for high school graduates that don't necessitate postsecondary education).”

Some affected institutions have been beset by other issues, including Birmingham-Southern, which never recovered from major missteps in calculating financial aid in 2010. That led to steep budget cuts and layoffs, exacerbated by a building boom that ate into its reserves.

Small, nonwealthy private institutions typically face the greatest likelihood of closure, experts say.

“The most vulnerable institutions are private (no public/state support), tuition-dependent, small (less than about 1,200 students), and regional (no broad reach beyond the local community or state),” Burns wrote. “These institutions are most at risk of enrollment declines due to the aforementioned factors and the least likely to be able to weather those challenges financially.”

The latest closures come after a steady stream of warnings from Fitch Ratings, Moody’s Investors Services, and S&P Global, all of which predicted increased challenges for the higher education sector in 2024.

With the demographic cliff looming and completion rates down for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid following the disastrous rollout of what was supposed to be a simplified form, colleges already struggling to maintain headcount could face more issues ahead.

“If the current trend continues … and we see fewer students completing the FAFSA as a result of the delay in the 2024–25 form, it is likely that there will continue to be enrollment declines in the coming years. If prior trends tell us anything about the future, we anticipate more closures on the horizon,” Burns wrote.