You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

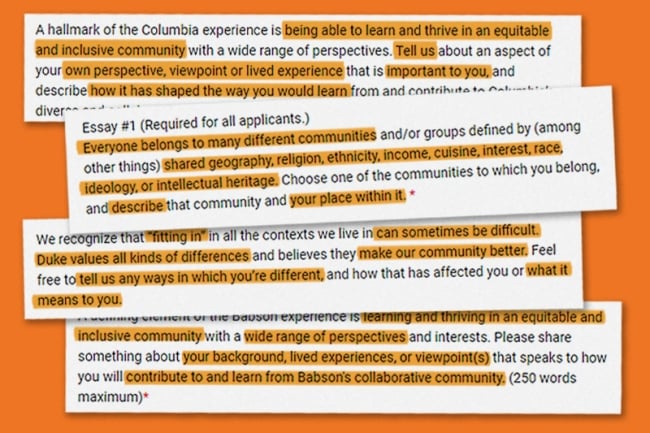

A new analysis of selective colleges’ applications found that many added essay prompts centered around identity and diversity after the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed

When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in two lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill last summer, the justices seemed to leave room for colleges to consider race through applicants’ essay responses.

“Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his majority opinion in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA).

Sonja Starr, a law professor at the University of Chicago, has been analyzing changes to college essay prompts since the fall. She told Inside Higher Ed that the “essay carveout,” as it’s often called, is a “meaningful path forward” for colleges trying to maintain their racial diversity. Her report on “Admissions Essays After SFFA,” published last month in the Indiana Law Journal, suggests that many selective colleges are taking the approach seriously, too.

For Starr’s analysis, which she says is the first piece of in-depth legal scholarship on the essay carveout, she examined applications for U.S. News and World Report’s top 65 colleges and universities—which are more likely to have used affirmative action in the past than most institutions.

She found that 43 of them had essay prompts addressing diversity, identity or adversity in the latest application cycle, up from 35 the year before. Thirty-one had mandatory questions on these subjects, an increase from 21, and the number of those with mandatory questions about applicants’ identity specifically increased from 11 to 17.

Those numbers, Starr is careful to note, don’t tell a straightforward story. Some of the questions that mention diversity are actually asking about “viewpoint diversity,” for example, and many of the prompts are open-ended enough to avoid charges that they are winkingly asking for an applicant to identify their racial background. But they offer “plenty of opportunity for students to convey race-related information,” Starr said.

And students often do—but not, as Starr found, particularly more after the affirmative action decision than before. She surveyed 881 students, about half of whom applied to college in the past year and the other half in 2022–23. Overall, she found that students who applied post-SFFA wrote about “race and ethnicity” slightly less than those who applied before. In fact, the only group that wrote more about their racial identity were non-Hispanic white students.

Testing the Waters

The essay carveout has proven to be one of the most hotly contested alternatives suggested in the court’s majority opinion. Many point to it as proof of the decision’s flexibility; the Biden administration even recommended using insight gleaned from essay responses as a way to boost diversity in its post-SFFA guidance.

Others suggest that any attempt to glean racial information from students’ essay responses—and then consider them in admissions decisions—is a clear violation of the law. Even Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in her dissent, dismissed the carveout as haphazard and self-contradictory, calling it an “attempt to put lipstick on a pig.”

“The Court’s opinion circumscribes universities’ ability to consider race in any form by meticulously gutting respondents’ asserted diversity interests,” she wrote. “Yet, because the Court cannot escape the inevitable truth that race matters in students’ lives, it announces a false promise to save face.”

Starr is less cynical. She believes that until the courts prove her wrong, the carveout “means what it says.”

“The court laid out what colleges are allowed to do: take into account anything that shapes an applicant's life experiences in a way that speaks to their potential to do well in college and add to the university community. What colleges are not allowed to do is use the essay just as a way of gathering information about the person's race, and then give automatic credit for membership in a racial category,” she said. “I think that’s a fairly clear line.”

Plenty of lawyers disagree on the clarity of that line. Art Coleman, founding partner of the higher ed law firm EducationCounsel LLC, told Inside Higher Ed in December that the amorphous boundaries between the “proxies” for affirmative action that Chief Justice John Roberts warned colleges not to pursue and acceptable “race-neutral” alternatives will remain blurry until lower courts define their contours through future legal challenges.

But as Starr noted, most colleges “do not have the luxury of waiting to see how courts resolve these questions.” This admissions cycle, they’ve been throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks, weighing their commitments to diversity against their aversion to the legal risks looming over their decisions.

Almost immediately after the Supreme Court’s June 29 ruling striking down race-conscious admissions, colleges began amending their applications and adding new essay prompts. Some did so as a thinly veiled rejoinder to the decision, like Sarah Lawrence College, which added a question quoting an entire passage from Roberts’s majority opinion weeks after it was passed down. But most new prompts simply work in language that implies a concern with one’s identity, like “adversity” or “lived experience.”

Starr said that in reviewing the new prompts, she’s been hard-pressed to find more than a couple that seem engineered to evince racial demographic information alone.

“The questions are so amorphous … I just don’t think they are what are gonna get colleges into trouble,” she said.

Waiting to Pounce

As colleges work out how to best make use of essays in a post–affirmative action landscape, a constellation of law firms and nonprofit advocacy organizations are waiting in the wings to hold institutions to the new law of the land.

“There was a lot of back and forth about essays and how they might be used unlawfully to find out racial information during the oral arguments in [Students for Fair Admissions],” said Alison Somin, a fellow at the Pacific Legal Foundation, which has filed suits in racial discrimination cases citing the SFFA decision. “In the end, Chief Justice Roberts basically said, you can't use the essay to try to get around what we prevented you from doing directly … if there was evidence of colleges doing that, we would absolutely challenge it in court.”

She also said that PLF and others—like the law firm Consovoy McCarthy, which was involved in the SFFA case—are waiting on a clear demographic picture of the newly admitted class of 2028 to emerge. If selective colleges now barred from using affirmative action had higher levels of racial diversity than before, Somin said that alone could be cause to investigate those institutions’ admissions practices and ensure they’re in compliance.

Will statistics be enough to land colleges in legal trouble? Starr said there’s always a chance, but she doesn’t think so.

“I am worried that some courts might get tricked by that argument,” she said. “But showing that the diversity of a school didn’t change much is extremely weak evidence … Plaintiffs in civil rights cases don’t win just by pointing to numbers.”

The way to stave off that risk, Starr said, is by making sure to emphasize a variety of qualities in evaluating essay responses, not just race and identity-based experiences. Navigating the essay carveout strategy thus becomes much more important for admissions offices looking to keep their institution out of hot water.

PLF is currently focusing on competitive public charter and magnet schools in its affirmative action litigation, including a highly anticipated case involving an elite Boston public which was placed on the Supreme Court’s docket last month. But Somin said she’s seen and heard too much evidence that colleges are trying to “get around” the Supreme Court ruling for organizations like hers to ignore, and that there’s nothing universities can do to avoid a coming litigative onslaught.

“I think there are enough hints out there that people are trying to cheat the SFFA ruling using essays that one of these days there’s going to be a prominent case in this area,” she said. “Even if it’s not the next month or the next three months, it will be coming.”