You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Colorado officials want to calculate the economic value of public higher ed for the benefit of students and institutions, but some are wary of the project.

Metropolitan State University Denver

Amid faltering enrollment rates and increased national scrutiny of the price and worth of a college education, Colorado is weighing a new formula to measure the “economic value” of degree programs offered by the state’s public institutions of higher education.

In its latest annual strategic plan, the Colorado Commission of Higher Education has proposed a way to calculate that value using not only the return on investment from expected income, but also a number of other variables—most notably, the “opportunity cost” incurred by attending college instead of working full-time.

The goal, according to commission vice chair Josh Scott, is to ensure that every degree meets a “minimum threshold” of economic value—in other words, to guarantee that students who pursue a postsecondary degree are making “at least more than they would with just a high school diploma.”

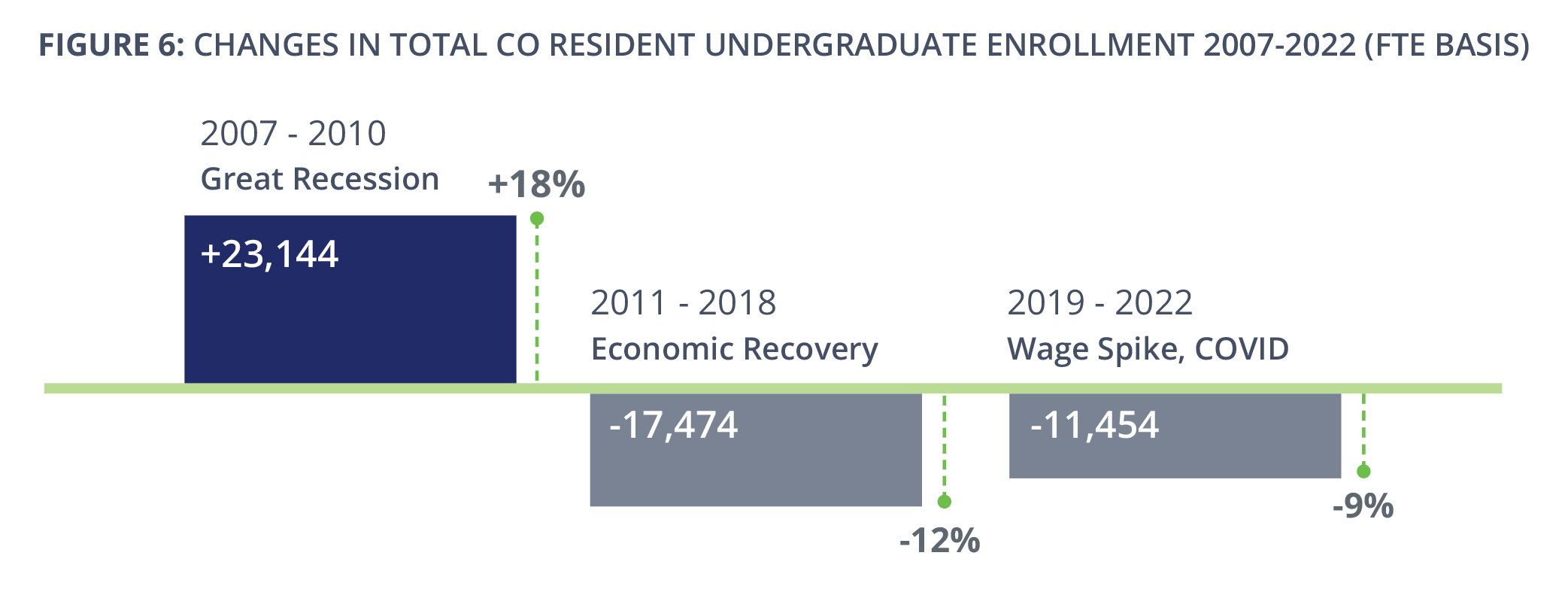

Scott said the primary impetus for the proposal was a “steady and recently accelerating erosion in enrollment,” linked in part to growing skepticism among students and families about the value of paying for a college degree.

“It is really important that we find a way to reverse that trend,” he said. “To do that, we need to make sure that the value proposition of postsecondary is much more resonant with learners than it’s been over the past 12 years.”

Scott added that the initiative is not meant to be punitive but is designed to give institutions additional information to work with when planning their program offerings and deciding where to invest resources—or trim fat.

But some leaders of Colorado’s public institutions are skeptical.

Janine Davidson, president of Metropolitan State University of Denver, said that given the state’s declining higher ed enrollment, shortage of teachers and health-care workers, and a budget crisis caused by decades of state disinvestment, placing a numeric value on degree programs seems like a low priority.

“Putting out a report like this is like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” she said. “We should be doing everything we can to encourage—and in fact help pay for—Coloradans to go to college.”

The Crest of a ‘New Wave’

In the strategic plan, the commission notes the proposal is part of a “new wave” of higher education policy focused on value rather than enrollment or degree attainment. While that wave isn’t exactly new, it has been gathering force in recent years, especially given the public’s diminishing faith in higher education as a path to economic success.

The commission’s proposal builds on a decade of initiatives at both the national and state levels, most famously the Obama administration’s College Scorecard and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Postsecondary Value Commission, launched in 2019. Just two months ago, the National Association of System Heads unveiled a campaign called College Is Worth It, which aims to demonstrate—as the name implies—the material benefits of a college degree.

At the state level, the University of Texas system launched a database linking degrees to workforce outcomes in 2014; the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education began collecting similar data in its workforce outcomes database in fall 2021.

Michael Itzkowitz, founder and president of the higher education consulting group HEA, said the Colorado proposal will be a useful experiment for other states looking to tackle the thorny issue of degree value.

“States are slowly but steadily using economic value in addition to attainment to determine whether or not they’re succeeding in higher education,” he said. “We’re seeing Colorado take the lead on this and at least providing a framework.”

The Colorado proposal is also unique in a number of important ways—particularly its recommendation that an opportunity cost metric be established to account for the “unseen” price of forgoing two or four years of full-time work to pursue a degree.

“Opportunity cost from a magnitude standpoint is at least as big if not bigger than tuition, fees and housing,” Scott said. “That’s particularly true right now when you can make north of 20 bucks an hour working at Amazon … walking away from 40 or 50 thousand dollars a year is a real trade-off, particularly for somebody that comes from precarious economic circumstances.”

While the strategic plan does not lay out a specific formula for opportunity cost, Scott said he imagines the technical task force assigned to create one will “keep it really simple” by comparing the median income for non-college-educated Coloradans to that of degree holders from a wide array of programs offered by the state’s public institutions.

While the strategic plan does not lay out a specific formula for opportunity cost, Scott said he imagines the technical task force assigned to create one will “keep it really simple” by comparing the median income for non-college-educated Coloradans to that of degree holders from a wide array of programs offered by the state’s public institutions.

John Marshall, president of Colorado Mesa University, said he’s worried that adding the opportunity cost metric will send the wrong message to students: that not attending college at all could be a “reasonable option” for some high school graduates.

“To make a calculus that includes the option of stocking shelves with no college education and say that’s a perfectly acceptable outcome … that seems to be a nonstarter,” he said. “You can’t start by hardwiring a disincentive for them to do any college right out of the gate.”

Angie Paccione, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education, said she understands the opportunity cost metric is “a bit of a tough pill to swallow,” particularly from an equity perspective, but added that she’s confident such concerns can be addressed as the plan is workshopped and finalized.

“If you come from an affluent family, you might be able to have a job out of high school that pays way more than if you’re from a low-income family,” she said. “As we talk about the strategic plan, we will need to do a stronger job of recognizing that opportunity cost is very, very different for communities of color.”

Tanya Garcia, Pennsylvania’s commissioner of higher education and the former associate director of postsecondary policy research at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, said value-measuring initiatives are most important for associate degree and credential programs. That’s because students enrolled in those programs expect a direct link between attainment and income possibilities, and because state policy makers turn to such programs to help solve workforce shortages.

“It’s important to policy makers because some of those programs train for high-priority occupations, and a state might have a vested interest in investing and subsidizing the cost of those,” Garcia said. “Without that data, we don’t know enough about the impact those credentials really have on individuals.”

Concerns About Funding, Messaging Fuel Doubt

Some of Colorado’s higher ed leaders say economic metrics can’t sufficiently illustrate the value of a college education. They worry that a mathematical formula based on economic outcomes will necessarily disadvantage schools with more working-class students or graduates in lower-earning professions, such as teaching and social work.

“If you start tagging the ROI on every single degree program, does that mean that we don’t find value in studio art and musical theater? And many much-needed jobs in Colorado are not lucrative; we don’t want to make students think social work or teaching aren’t good routes,” Marshall said. “As we work through these tricky questions about inputs and outputs, our concern is going to be making sure we fight for the long-term values of our community and [do] not inadvertently disincentivize certain areas of study.”

Last September, the University of Colorado released its own “value index” for higher education in the state, broken down by degree type. In addition to earnings, it also factors in variables like civic participation and “general happiness.” Davidson said those intangibles, while harder to wire into a mathematical formula, are what appear to be missing from the commission’s proposal.

Scott said that while the noneconomic benefits of a degree are important, he believes it’s crucial for learners to know there’s a “minimum economic viability” to pursuing a degree.

“The rest of those benefits, all the other great things that come from a postsecondary education, are fundamentally inaccessible to you if you can’t even afford to go,” he said. “Humanities majors want jobs, too.”

Other leaders are worried that the new index might have unintended consequences for state funding and public attitudes toward higher ed, further damaging the state’s already underresourced public institutions. Out of all 50 states, Colorado provides the second-lowest amount of support to public higher education, according to the latest data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

While Davidson hopes that publishing the economic value data would prompt lawmakers to subsidize programs that don’t currently make economic sense for students, she said she knows it could have the opposite effect, giving detractors in the statehouse more ammunition to cut higher ed spending.

“There’s always a risk that our elected officials are going to take the data and drive recklessly on the highway with it,” she said. “Whatever they’re trying to prove here, they have to be careful to do no harm.”

Itzkowitz said that while he understands concerns about the potential consequences for state funding, he thinks it’s better to base those funding decisions on concrete data rather than pure ideology.

“The cultural ideology part doesn’t necessarily align with the data; a liberal arts education often shows economic return at the four-year level, for example,” he said. “Comparatively, making data-driven decisions is very reasonable in terms of what to fund, determining what’s not working and improving things that are.”