You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

International students wave their home country flags at Northeastern University’s 2019 commencement ceremony. International enrollment bounced back last year after a steep decline during the pandemic.

Courtesy of Northeastern University

International student enrollment bounced back last year after a steep pandemic-fueled decline, according to a new “Open Doors” report from the Institute of International Education. The total number of international students in the U.S. increased by 4 percent in the 2021–22 academic year and an additional 9 percent this fall, following a 15 percent drop in 2020–21.

Allan Goodman, IIE’s CEO, said the rebound is consistent with historical precedent.

“We have over 100 years of data on international student mobility to the United States. This data includes 12 pandemics and shows that educational exchanges occur even during them and grow rapidly afterwards,” he said.

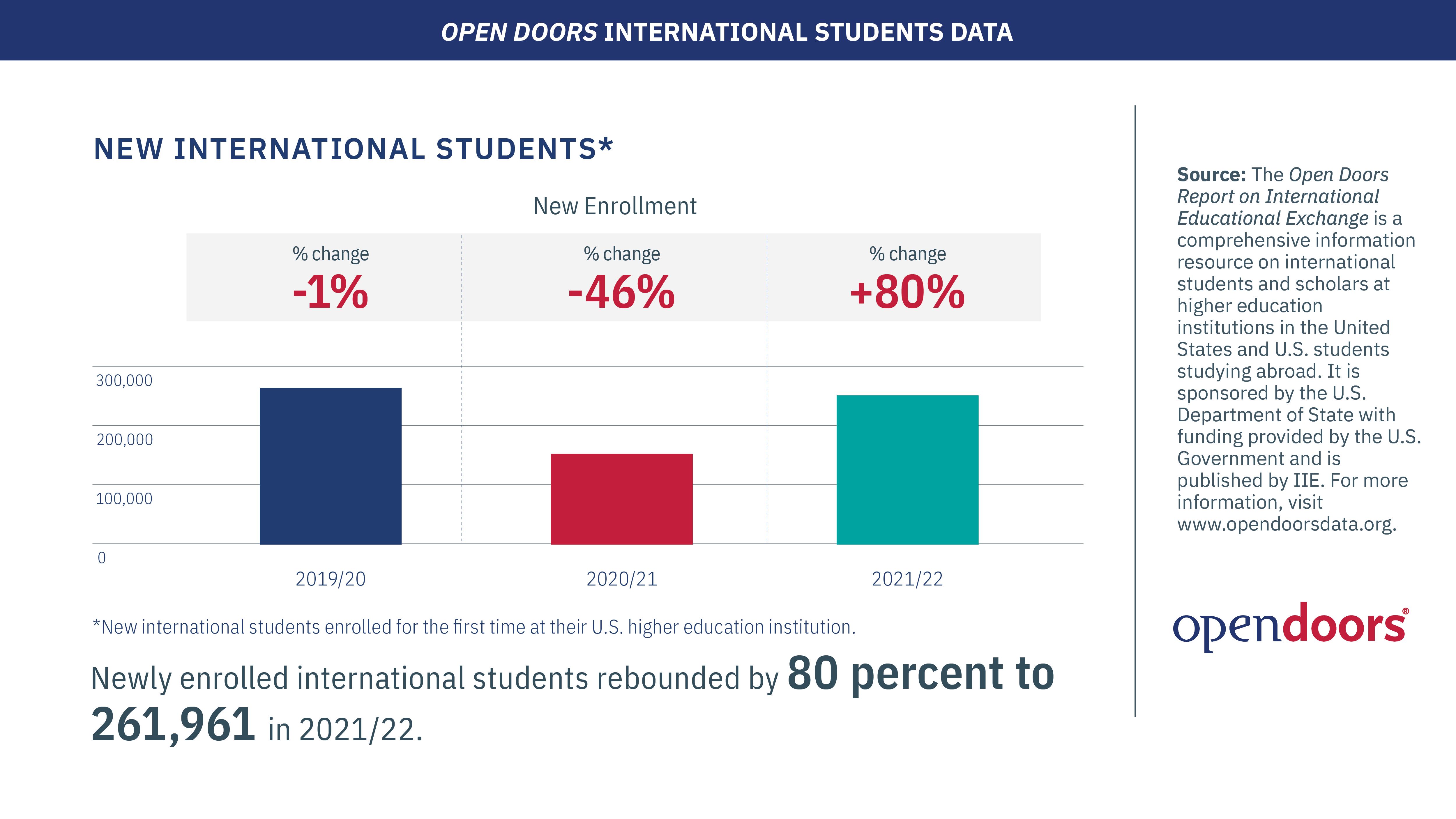

In 2020–21, new international enrollments in U.S. colleges and universities dropped by over 100,000, cutting the previous year’s numbers almost in half, according to the report. But last year, new international student enrollment increased by 80 percent, returning to just below pre-pandemic levels.

The report also found that 90 percent of enrolled international students returned to in-person learning last year, and that international students accounted for 4.7 percent of U.S. higher education’s total student population.

Mirka Martel, IIE’s head of research, evaluation and learning, said the jump likely occurred because students who’d been accepted during the pandemic but deferred for a year finally came to campus.

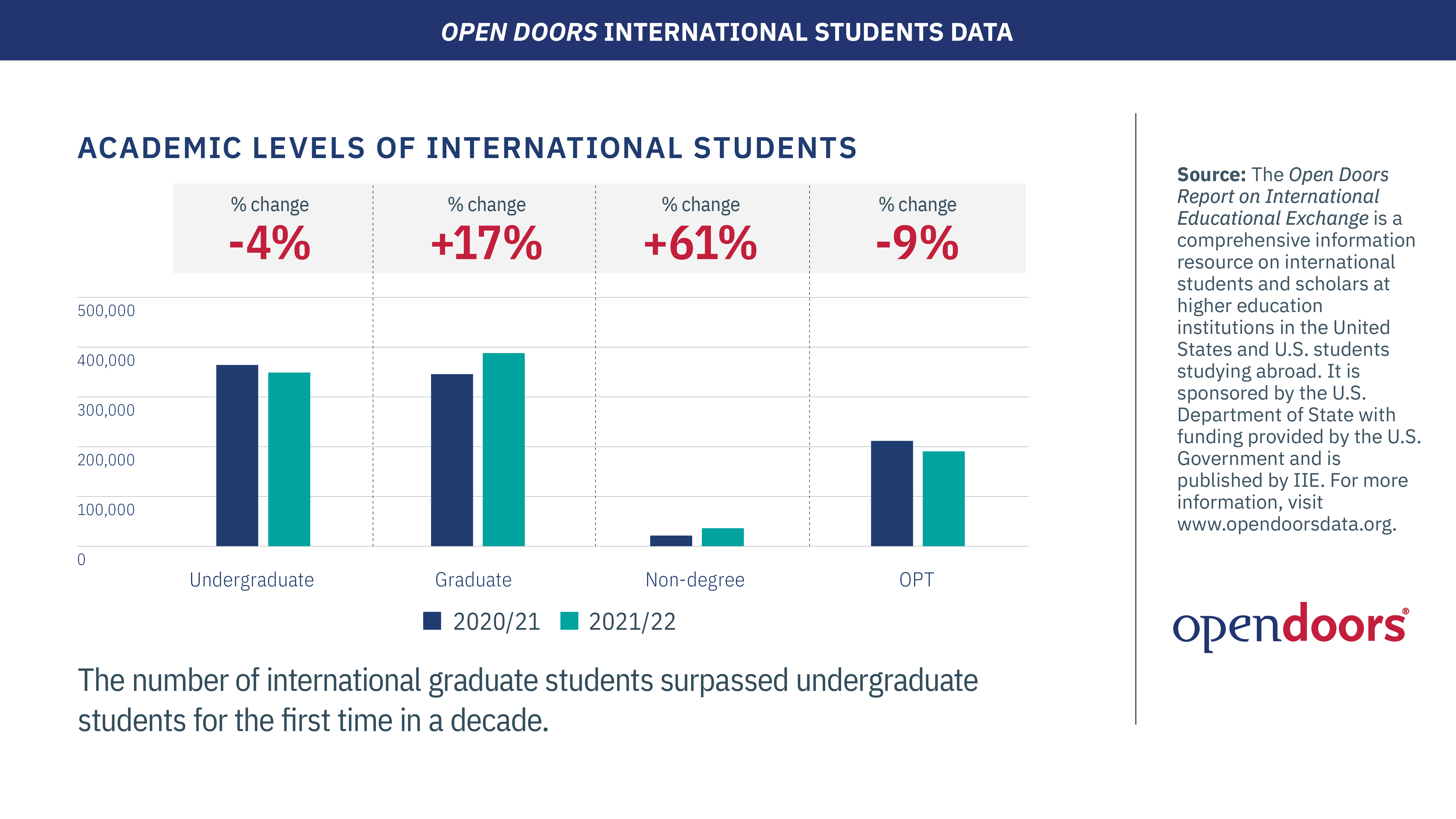

International graduate students saw the largest rebound, rising by 17 percent and surpassing pre-pandemic levels of growth. Last year marked the first time in a decade that international graduate students outnumbered undergraduates. The report also found that math and computer science surpassed engineering as the primary field of study for international students, with an increase of 10 percent last year.

But among some groups, the pandemic-triggered decline continued, albeit less drastically. While enrollment of first-year international undergraduates rose by 20 percent, total international undergraduate enrollment fell by 4 percent, suggesting that many students who moved home during the pandemic did not return.

Still, Martel said the overall picture is rosy, and she’s hopeful that trend will continue.

“Less than two years following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, student mobility has made a strong comeback,” she said. “These findings highlight the continued resilience of international educational exchange and the commitment of U.S. colleges and universities to host international students.”

Enrollment From China Still Down

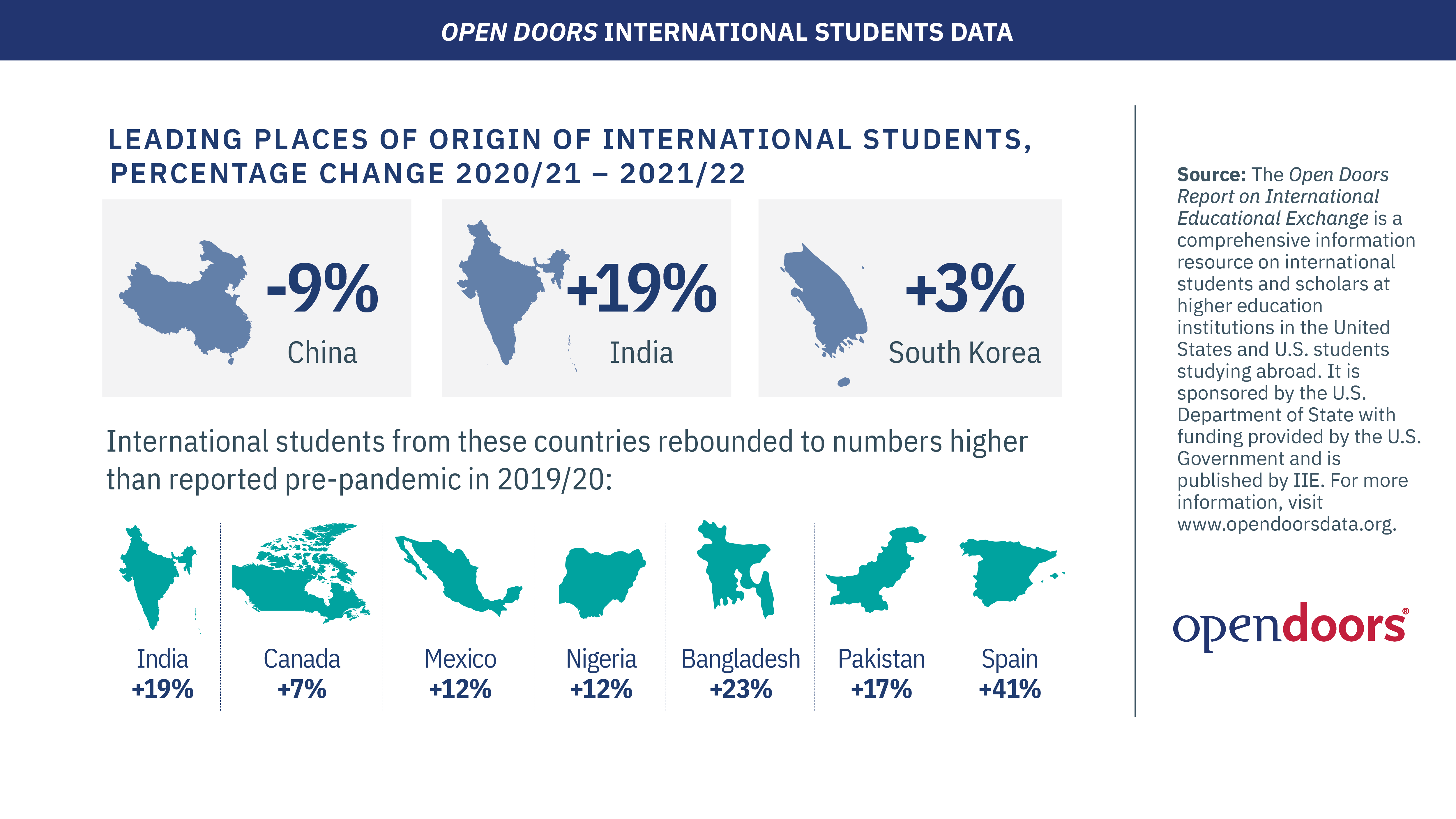

Notably, Chinese student enrollment continued to fall in 2021–22, dropping another 9 percent overall and 13 percent among undergraduates. That follows a nearly 15 percent drop in 2020–21.

Even so, China remained by far the top source of international students for U.S. institutions. But India, the No. 2 source, saw a 19 percent jump in U.S.-bound students, slowly closing the gap.

Ethan Rosenzweig, the deputy assistant secretary for academic programs at the U.S. Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, said one hurdle institutions have faced in rebuilding international enrollment from China is that recruiters still aren’t allowed to enter the country due to COVID-19 restrictions.

“The Biden administration has been very clear that Chinese students are welcome here,” he said. “I’m looking forward to the [People’s Republic of China] opening its borders for U.S. universities to recruit in person very soon.”

Rachel Banks, senior director for public policy and legislative strategy at NAFSA: Association of International Educators, said the continued difficulty in gaining back Chinese students—a longtime priority of international recruiters—illustrates the need for more targeted recruitment from other countries.

“Increasingly over the past several years, I think it has become clear how important it is to diversify international student enrollment so we’re not just relying on one or two countries,” she said.

A National Strategy for an International Problem

One major reason international students are so important to the U.S. is because of their economic impact, Banks said. Today, NAFSA released a report on economic value of international students—both to the higher education field and to the U.S. economy as a whole—that found that the group contributed nearly $34 billion to the U.S. economy last year, which is still $6 billion below the pre-pandemic high-water mark.

The calculation takes into account “both the micro and the macro,” Banks said, from the purchasing power of students in their host communities to the research and business contributions of graduate and postgrad students. Their tuition dollars are also an important source of revenue for many institutions, especially publicly funded colleges and universities that have used international enrollment as a way to offset cuts to state funding.

Banks said the IIE data, while promising, highlight an issue she and her organization have raised with government officials for years: the need for a “national strategy” on international recruitment.

“For a long time, we’ve really coasted on just having a strong higher education system compared to most other countries and have relied on that as a calling card for attracting students,” she said. “But we’ve been increasingly outmaneuvered by competitors who have moved aggressively to define their own national strategies.”

Banks said those competitors—Canada and the United Kingdom, chief among them—work to develop policies on immigration and work visas that make it easier, more appealing and more affordable for international students to study there. She wants the U.S. to do the same.

“We need to make sure that we’re pulling from a broader number of countries and also, within those countries, from all levels of society and not necessarily just those students who can afford the price tag,” she said. “That is definitely a hurdle that we face against some competitors, is that we are by far one of the more expensive destinations for an international student.”

She also noted that international students may have been turned off from studying in the U.S. by a number of recent external factors: American mismanagement of the pandemic, increasing xenophobia and the threat of widespread gun violence among them.

“International students are very savvy in thinking about their destinations beyond just the institution,” Banks said. “We were already seeing international student enrollment decline before the pandemic, and COVID really put a lid on it. We’ve seen that lid lift a bit with this latest data, but it’s not where it was or, really, where it needs to be.”

U.S. Students Stayed Home

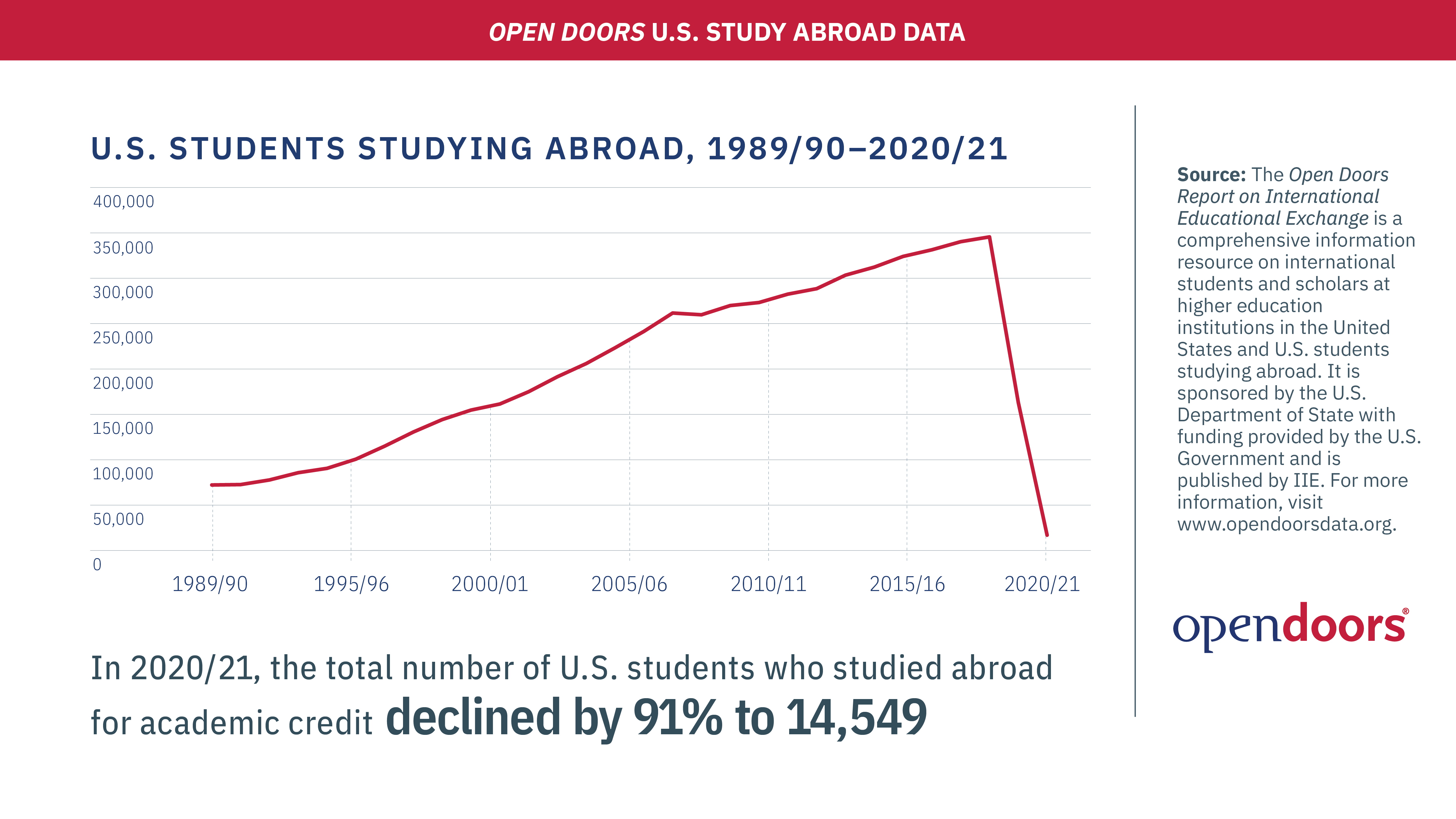

The Open Doors report also includes data on U.S. students studying abroad during the 2020–21 academic year—which is a year behind the enrollment data and reflects the impact of the pandemic on forcing the vast majority of American students to quickly return from overseas or cancel upcoming study abroad plans. The number of students studying abroad plummeted by 91 percent, according to the report, and nearly 60 percent of students who did study abroad that year did so during the summer of 2021.

The top destination countries remained relatively stable throughout this decline, with Italy, Spain, France and the United Kingdom topping the list, as they did in 2019–20. South Korea advanced to the No. 5 spot, while Denmark and Costa Rica, previously popular destinations, experienced more dramatic declines.

Over all, fewer than 15,000 U.S. students studied abroad during 2020–21, compared with over 150,000 the previous academic year. However, nearly 33,000 students participated in online global learning opportunities, a category that included remote internships, videoconference dialogues and classes with foreign institutions.

“This showcases how U.S. institutions nimbly reacted to provide students with online opportunities when they were unable to travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” Martel said.