You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Viktoriia Hnatiuk/Getty Images

When Ryan Weger was a high school student in Northern Virginia, he longed to attend Virginia Tech for college. But he changed his mind after his father returned to college in his late 30s and earned an online, competency-based bachelor’s degree at Western Governors University in a single year.

“He slammed it,” Weger said of his father’s accomplishment. Weger reconsidered his aspiration to attend Virginia Tech which, by his estimation, might have “required four years, left [him] $100,000 in debt, and with only one degree.” Besides, he noted, “I’m much better at reading the text myself instead of having somebody lecture at me for hours.”

Soon after high school, 18-year-old Weger started work as a data center technician at Amazon Web Services and enrolled at Western Governors. There, he pursued an accelerated online program that, like his father, allowed him to graduate in one year—at the age of 19.

“I walked away spending only about $7,000. I also walked away with a [bachelor’s] degree and seven industry certifications,” Weger said. “It was a no-brainer.”

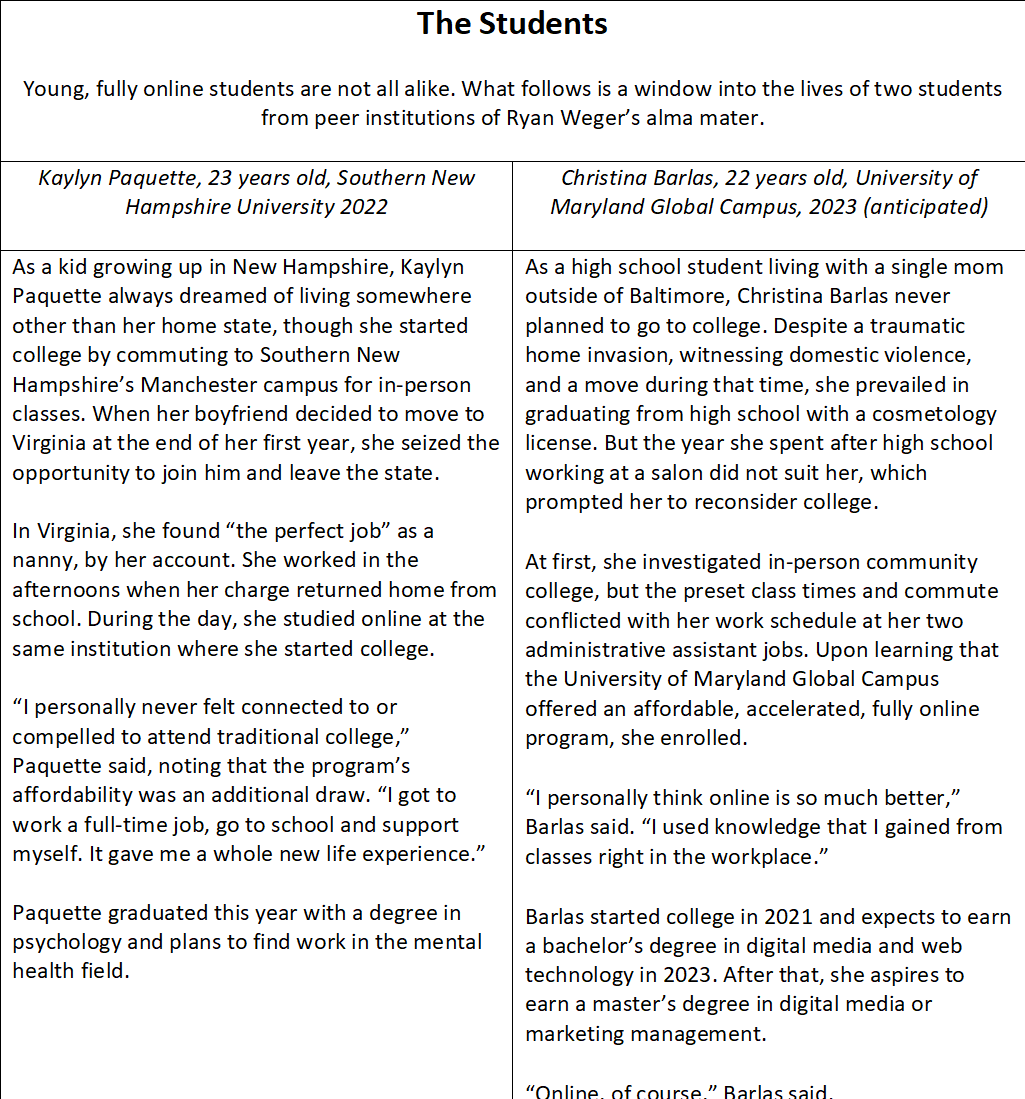

National online universities like Western Governors and Southern New Hampshire University remain primarily destinations for working adults, which has allowed leaders of many traditional colleges and universities to think of them as “other” and not as competitors. It’s premature to know whether their growing numbers of traditional-age students signal a larger shift in enrollment patterns toward fully online learning.

But a national survey conducted in 2022 suggests that the number of high school juniors and seniors planning to attend fully online colleges has more than doubled since before the pandemic. Though this population is still small, the tens of thousands of traditional-age undergraduates big online universities are now enrolling would be eagerly welcomed by the many four-year residential campuses and community colleges that are seeing their enrollments fall.

The Numbers

Big online universities experienced massive growth across the board during the pandemic. Southern New Hampshire, for example, grew from 135,000 students in March 2020 to 175,000 today, according to Paul LeBlanc, the institution’s president.

Before the pandemic, Southern New Hampshire enrolled approximately 33,750 online students who were under 24 years old. Today, that population has grown to approximately 43,750 students. The extra 10,000 students could, on their own, populate a midsize traditional university, or several small liberal arts colleges.

“When we first started online years ago, we certainly didn’t have anything like that number” of young students, LeBlanc said. At that time, “we routinely said that traditional-aged students really don’t gravitate online.”

At Western Governors, traditional-aged student enrollments have more than doubled—from approximately 6,000 students in 2017 to 15,000 students in 2022. Like Southern New Hampshire, Western Governors’ young, fully online student population rivals that of a traditional, midsize university, or several community college campuses.

“Conventional thinking says it’s mostly nontraditional adult learners who utilize online. Historically that has been largely true for us,” Scott Pulsipher, the president of Western Governors, said. “But over the past five years, the 18- to 24-year-old population has been one of our fastest-growing age categories … We anticipate much of that demand to continue.”

At University of Maryland Global Campus, an institution with a sizable cohort from the military, the population of fully online students under the age of 24 started off smaller than at its peer institutions, though it has increased by 33 percent in recent years—from nearly 4,300 students in 2017 to 5,700 students today.

“That increase was going on even before the pandemic,” said Greg Fowler, UMGC’s president. “Eighteen- to 22-year-olds are actually our single largest, fastest-growing group.”

These enrollment surges of young students at big online universities serve as supporting evidence of a single statistic on annual surveys conducted by Eduventures Prospective Student Research that ask tens of thousands of high school juniors and seniors about their planned college delivery mode. In 2020, before the pandemic, 0.28 percent of the high school respondents said they planned to attend college fully online. In 2022, that figure more than doubled, to 0.72 percent.

These enrollment surges of young students at big online universities serve as supporting evidence of a single statistic on annual surveys conducted by Eduventures Prospective Student Research that ask tens of thousands of high school juniors and seniors about their planned college delivery mode. In 2020, before the pandemic, 0.28 percent of the high school respondents said they planned to attend college fully online. In 2022, that figure more than doubled, to 0.72 percent.

“In absolute terms, it’s tiny, but in relative terms, that’s a big jump,” said Richard Garrett, chief research officer at Eduventures. “If you’re a prestigious, well-known, oversubscribed institution, then this isn’t of concern to you, because you have far more demand than supply. It is a threat to many institutions that are not in that category, and that’s most institutions.”

The Drivers

These large online universities that are experiencing noteworthy surges in young, fully online learners are at work making sense of the phenomenon. A team at Southern New Hampshire, for example, has identified four drivers, according to LeBlanc.

First, some students find that online learning works better as they manage health concerns. Second, some have significant responsibilities, including full-time work or care for parents or children.

“We sometimes forget that some traditional students face all of the same pressures as 31-year-olds,” LeBlanc said.

Third, some prioritize affordability. Not only is online college typically priced lower than in-person college, but some programs are competency based, which can accelerate progress to the degree. Further, online students often have more flexibility to work while attending college, which can reduce opportunity costs.

Finally, some are exceptional in some way; they may be athletes, performers or entrepreneurs whose primary focus is on advancing those pursuits, and earning a college degree is a secondary goal.

All the presidents with whom Inside Higher Ed spoke invoked—either explicitly or implicitly—Clay Christensen’s “jobs to be done” theory. That is, many high school graduates have (at least) two jobs to be done: earn a degree and transform into an adult.

In-person college has historically promised a pathway for both. Students who attend college on a residential campus can live apart from their parents, gain leadership experience in clubs and sports, pursue internship and work opportunities, and even fall in love—all while making progress toward a degree that may lead to a job.

But in these COVID times, some young students have unbundled the job of pursuing a college degree from the job of emerging as an adult.

“There’re a lot of young people who don’t need a coming-of-age experience,” LeBlanc said. “For whatever reasons and whatever ways, they’ve had that. They know what they’re about, or that’s just not the question that drives them right now.”

The pandemic also introduced remote learning on a societal scale, which helped destigmatize online degrees. A 2021 study by Northeastern University, for example, found that nearly three-quarters (71 percent) of employers perceive online educational credentials as on par with or of a higher quality than those completed in person.

Also, just as employers are negotiating return-to-work policies with their employees, colleges are now negotiating their balance of online, blended, hybrid and in-person learning options in ways that young digital natives find attractive.

“Online college isn’t a leap,” LeBlanc said. “They think, ‘I do everything else online. I’ll do this online.’”

The Challenges

These college presidents welcome their enrollment surges, even if they acknowledge challenges.

Before the pandemic, four out of five (80 percent) Southern New Hampshire online students arrived with transfer credit. Now, only 65 percent of students transfer in credit, due in part to the influx of young students with little college experience. That’s challenging, LeBlanc said, as online students with zero to few credits fall into a high-risk population.

Online institutions collect abundant data on student engagement with their institutions, Pulsipher said. Such intel provides faculty members and mentors with timely, relevant information they hope will support student success.

“We’re not fundamentally doing something different” from how the institution served students before the surge, Pulsipher said. “We’re now just getting data about different types of learners that have become a higher percentage of our total population.”

At Southern New Hampshire, a team is working to make sense of online students’ expectations. Many of the asks are predictable, given the youthful influx. The students want their studies to be accessible and frictionless on mobile devices. They welcome chat bots and want to be able to jump on a call with a faculty member, even as they walk down the street, according to LeBlanc. They want the convenience of asynchronous work coupled with the humanity of synchronous meetings.

“Everyone got used to zooming with Grandma in the last two years,” LeBlanc said. The institution is planning digital upgrades in response to the feedback, which LeBlanc expects will be popular among all students.

Fun digital upgrades aside, these leaders are aware that many young students who opt to attend college fully online due to significant health, work or family concerns face nontrivial hurdles.

“How do we operate in a world where, for some portion of our students, we will never be better than their third top priority after their current jobs and their family?” Fowler of UMGC asked. Jobs and family responsibilities are often demanding on their own; college courses add to that load.

The Impact

Ten thousand unexpected young students “voted” for Southern New Hampshire with their enrollment, and another 9,000 unexpected young students voted for Western Governors with their enrollment. Those are strong numbers, according to Garrett of Eduventures, especially as the young students appear to have found the big online universities on their own, rather than having been targeted as prospects by the institutions.

“If you look at our television commercials, and we have lots of them, none of them market to traditional-aged students,” LeBlanc said.

That may suggest a macrophenomenon, according to Garrett, suggesting that many predominantly online colleges beyond these two institutions may also be experiencing enrollment surges of young, fully online students.

“Once we’re in the tens of thousands, that suggests that we’ve surpassed anything we’ve seen historically from these wholly online schools and this age group.”

Young students who are part of the current enrollment surge may be drawn to the convenience, flexibility and affordability of online college, but their trajectories are to be determined. Garrett posed a question: How many of them entered with their eyes open?

If the young students discover that the pragmatic benefits outweigh any experiential limitations, such as feeling isolated, then they may tell their friends. That could lead to a positive feedback loop that increases demand for big online colleges among young students, Garrett said. If, on the other hand, these young students determine that they “just can’t stand all this online,” then they may rejigger their enrollment by seeking out in-person pathways.

For now, big online universities’ market share of young students is small, which may provide a modicum of reassurance for traditional residential campuses that court young students.

“But in a tight market with declining enrollment, nobody wants anyone taking a few digits of market share,” Garrett said.