You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Monkeypox cases have been reported on five college campuses this summer.

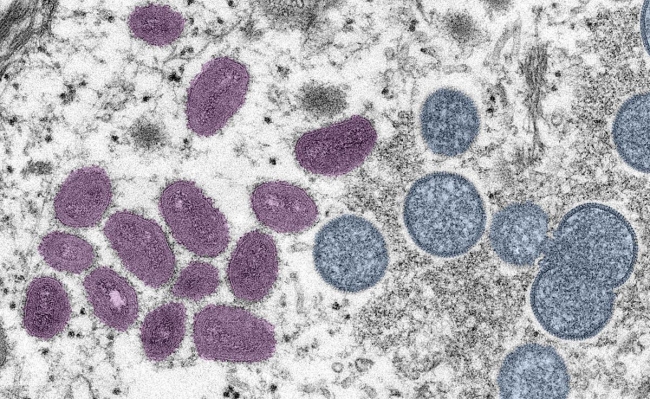

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

When students return to campus this fall, the latest COVID variant isn’t the only virus they’ll have to worry about. Monkeypox, a painful but nonfatal virus spread primarily through skin contact, is on the rise—and with the fall semester rapidly approaching, many institutions are starting to prepare for potential outbreaks.

There have been over 6,600 confirmed cases of monkeypox in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over half of which were reported in the past two weeks. Yesterday, the Biden administration declared the virus a national health emergency; California and Illinois declared states of emergency last week, as did New York City.

Colleges have not been immune to monkeypox even during the quiet summer months, when places of potentially high transmission—such as dormitories, gyms and lecture halls—are largely empty. Confirmed cases have been reported at the University of Texas at Austin; Georgetown University and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.; and West Chester University and Bucknell University in Pennsylvania.

Many experts are encouraging colleges to begin preparing for possible outbreaks, citing their densely populated residential settings and fluid social and sexual networks.

“There’s definitely potential for colleges to become a hotbed for infection,” said Rachel Cox, an assistant professor of nursing who studies infectious disease and epidemiology at the MGH Institute of Health Professions. “After two years of social isolation, students are likely going to be interested in heavy socialization, and not just sexual activity but also other types of close contact … I think it would be wise for colleges to plan for how to prevent outbreaks on campus and what to do if an outbreak occurs.” (This paragraph has been updated to correct Cox's title and place of employment.)

Some institutions have begun that planning process in earnest. David Lakey, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer at the University of Texas system, said system officials have been meeting with risk managers at various UT campuses to discuss preventative measures, messaging campaigns and containment and care strategies.

“Universities are working through this on their own right now, without any formal CDC guidance,” he said.

The CDC has issued guidance for dealing with monkeypox in congregate living settings, but none specifically for higher education institutions. A spokesperson for the American College Health Association told Inside Higher Ed that while there are currently no official ACHA guidelines regarding monkeypox, the organization is working on drafting best practices for preventing and containing infections on campus.

Panic-Free Planning

Two years of developing COVID safety infrastructure—including isolation housing, virus testing sites and contact tracing—may help colleges deal more effectively with monkeypox cases on campus.

“We should be preparing, learning and growing from COVID, taking the lessons we learned and using them to protect others,” Cox said.

Lakey said that developing close connections with local and state health departments will be crucial in coordinating the testing, treatment and containment of monkeypox on campus.

“This is really one of those situations where [institutions] need to dovetail into the local response and be part of that, versus having something that’s totally separate from what the local health departments are doing,” he said.

Lakey also stressed that the messaging about monkeypox should be different from that about COVID-19, given that it is highly unlikely for campuses to see widespread transmission simply through students and staff occupying the same living and learning spaces.

“It’s important right now to remember that this is very different from COVID, and that transmission really has been through intimate contact,” he said. “The vast majority of students are at low risk … there is a potential to overreact that has its own consequences.”

Jay Varma, professor of population health studies at Cornell University’s Weill School of Medicine, said that the risk of contracting the virus through nonintimate contact appears relatively low. Still, he said, there are “a lot of unknowns” that make it hard to write off the possibility that the virus could spread without skin-to-skin contact.

“Gay sexual networks, those who are [hooking up] and going to sex parties, those are really intense environments, so there’s a lot of close contact and a lot of people in proximity. I don’t know how much that plays out on college campuses,” he said. “But if and when cases do occur on campus, there’s always going to be the possibility that it might get spread through nonsexual means … It’s an unsatisfying answer, but we just don’t really know.”

Cox said she wouldn’t count out more serious monkeypox outbreaks on college campuses, and she urged students and university leaders to be prepared. Symptoms include fever, headache, sore throat, cough, chills and a painful rash.

“Students and campuses should consider that they could get hit by the storm, and they should be ready for that,” she said.

Varma said that after COVID-19 and monkeypox, colleges should learn to incorporate viral infection infrastructure into their institutional planning, rather than simply as a temporary response to passing crises.

“This is a new age of pandemics. Universities shouldn’t think of COVID as a once-in-a-lifetime thing, or monkeypox as some strange aberration,” Varma said. “We can’t predict what the next threat will be, but I can tell you with absolute certainty that something like this will happen again and your campus will be much safer if you make these systems you put in place part of an ongoing institutional structure as opposed to something you only do when you hear about a new outbreak.”

Avoiding Stigma With ‘Compassionate’ Caution

One of the major messaging challenges regarding monkeypox—for colleges as well as government health departments—is how to alert and protect the most vulnerable communities without stigmatizing LGBTQ+ people.

Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted disease or infection, but the vast majority of cases have been diagnosed in men who have sex with men. According to a study from the New England Journal of Medicine, 98 percent of those who contracted the virus between April and June were men who identified as gay or bisexual.

The outbreak has prompted some homophobic backlash, and colleges have not been immune. Last month, a computer science professor at UT Dallas was reprimanded after he tweeted, “Can we at least find a cure for homosexuality, especially among men?” along with a link to an article about the virus’s prevalence among gay men.

Gregg Gonsalves, a professor of epidemiology at Yale University, was also a leading member of the prominent activist group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) during the height of the AIDS epidemic. He said that homophobia was much more socially acceptable when he attended college, but it’s still important for universities to make sure their strategy for dealing with the virus doesn’t stigmatize the LGBTQ+ community.

“Monkeypox can easily become a political football for right-wing people who have no shame,” he said. “I was coming out in college during the AIDS epidemic, and it was hard. Coming out in the middle of monkeypox would be hard, too."

Gonsalves added that colleges should prioritize providing preventative care and educational resources to the communities most vulnerable to monkeypox. He said that means safe-sex education that does not rely on promoting abstinence, like encouraging “sex pods”—small, self-contained groups of people who only sleep with each other—among single men who have sex with men. But it also means “modeling inclusive behavior” at the high levels of university leadership and messaging.

“The big question is, how will colleges reach out to gay students on campus?” he said. “As the school year gets closer, I’m hoping that universities have more explicit advice for their LGBT students, description of the facts about the disease and so forth, but also issue calls for compassion and solidarity.”

Lakey said UT campuses are looking to work directly with LGBTQ+ campus and community organizations to develop messaging and education that helps vulnerable populations avoid infection without stigmatizing their sexual identities.

“I think that’s one of the lessons from the past. As an older guy, I lived through those times,” he said, referring to the AIDS epidemic. “Bringing the impacted population to the table to help spread the message as a partner is key.”