You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

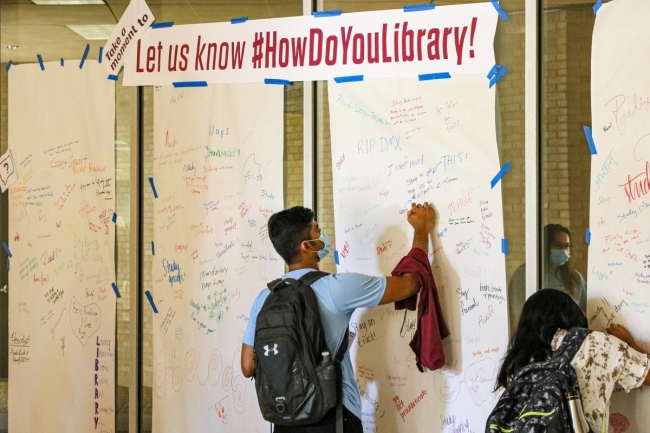

Changes coming to Texas A&M’s libraries have faculty members concerned about the loss of tenure for librarians.

Texas A&M University/Facebook

The Texas A&M University system is working on a plan that would make sweeping changes across its 10 libraries. Those changes, still being discussed, would include asking librarians to relinquish tenure or transfer to another academic department to keep it.

The plan grew out of recommendations from MGT Consulting, which Texas A&M hired in June 2021 “to conduct a high-level, comprehensive review of major functional areas,” according to a company report. But as administrators have suggested additional changes, including to employee classification, faculty members have pushed back, arguing that proposed structural changes to the library system will do more harm than good.

They are especially concerned about a proposal that would end tenure for librarians. Experts note that tenure for librarians, which is somewhat common in academia, though not universal, can be crucial for academic freedom, especially in a political environment in which librarians are under fire.

Faculty members have suggested that the change lacks rationale and that the plan—scheduled for implementation this fall—is being pushed through too quickly. Some details are still being finalized, and Texas A&M declined to answer questions about how the proposed changes will happen—or why.

An MGT Consulting spokesperson told Inside Higher Ed that it “has not weighed in on issues related to tenure” at Texas A&M. The idea seems to have emerged in the absence of transparent leadership regarding the process.

The Plan

Exactly how the Texas A&M library system will be overhauled has been the subject of speculation for months since plans became public. Early concerns included speculation that the administration would completely digitize the library and convert the physical building into office space, a notion that leadership has squashed. But such rumors underscore and illustrate concerns across the university system about changes that critics argue don’t make sense and aren’t being explained, leaving students and employees in the dark.

The plan from MGT Consulting is, of course, subject to the approval of Texas A&M leadership—including President M. Katherine Banks, who has already shot down or modified some of the suggestions. For example, the administration scuttled MGT Consulting’s recommendation that it place the university libraries in a new department of library sciences, to be housed in a newly created college of art and sciences.

But Banks noted in a December statement that she believes “a significant change is needed in the administrative structure of the libraries.” One of those changes is that “the University Libraries will no longer serve as a tenure home for faculty,” Banks wrote. “Tenured and tenure-track faculty currently in University Libraries will be accommodated in a new departmental home with a full-time appointment in the University Libraries service unit.”

Exactly what that means is still unclear. A working group focused on the libraries—one of many weighing the recommendations from MGT Consulting—noted in a March report that “faculty members [in the library] can transfer to an academic unit, with a partial or full-service appointment in the libraries” or they “can convert to full-time Library staff positions.”

Also in March, the Texas A&M Faculty Senate passed a resolution requesting that Banks “reconsider plans to alter the faculty and tenure status of university librarians and to refrain from advancing any other major changes to the library system without the involvement and support of major stakeholders, including students and faculty, especially the librarians.”

Dale Rice, a journalism professor and speaker of the Faculty Senate, said Texas A&M has not elucidated a plan to implement the proposed changes, meaning little is known about the ultimate fate of the university’s 82 librarians, an unknown number of whom are tenured.

“My understanding is that the recommendation was that if you wanted to retain tenure, you had to find a new departmental home and move to another academic department,” Rice said.

Texas A&M boasts strong rankings from the Association of Research Libraries—eighth among public institutions, 18th over all—Rice said, making him wonder why the changes are needed. Many faculty are concerned that forcing librarians to relinquish tenure or find a new department will ultimately lead to an exodus that will impact the quality of services available.

“I think what faculty members are looking for is a vibrant library, full of the kinds of services that exist today, and [that is] not diminished in any way after these changes,” Rice said, adding that there are concerns that librarians will leave and it will be difficult to replace them if tenure is not an option.

Similarly, the Faculty Senate resolution argues that “a decline in the quality of library services would impact research, classroom education and, ultimately, the accreditation of Texas A&M University.”

Asked to explain the justification for changes to the library, Texas A&M never provided a direct response to Inside Higher Ed. Initially, a university spokesperson said by email that “The proposed changes do not impact any current staff members with regard to tenure,” citing an MGT report.

However, a later statement seemed to directly contradict that.

“The three historic pillars of faculty are teaching, research and service. Most faculty are affiliated with programs that have undergraduate, graduate and possibly professional students. This is not the case at Texas A&M University. Therefore, tenured librarians that wish to remain tenured have been asked to affiliate with departments related to their field of specialization,” interim provost Tim Scott said by email. “These meetings have been supported by Faculty Affairs, the Interim Dean of Libraries, and the Department Head in question. The Librarians seeking to retain their tenure have all been successfully placed. Some librarians have opted to become professional staff for a variety of reasons, which may include focusing entirely on the traditional work of librarians versus teaching and research, 12-month salary, and/or the ability to accrue vacation.”

Asked to reconcile these seemingly contradictory statements, a Texas A&M spokesperson cited Scott’s busy schedule during commencement season and did not provide a further response.

The Pushback

In late April, an Academeblog.com post attributed to two anonymous Texas A&M librarians argued that the university has become a battleground for censorship.

The anonymous writers also alleged that “neither President Banks nor any member of her staff or MGT Consulting have ever provided the libraries with an explanation of the reasons or justifications—whether fiscal, administrative, or otherwise—for this reform, nor a rationale for its odd hastiness. (This reform was initially proposed in December 2021, and the administration has demanded its completion by the beginning of the fall 2022 semester.)” The writers also pointed to recent media reports of “relentless attacks on intellectual freedom and attacks on libraries.”

They argued that “libraries and librarians are at the forefront of mediating student access to multiple perspectives on topics and maintaining quality, unbiased materials. An attack on the academic freedom of librarians has a direct impact on the voices of marginalized groups.”

Public and school libraries across the U.S., particularly at the K-12 level, have come under fire lately, often from conservative politicians who want to remove, ban or even burn books. And everything is bigger in Texas, as the old saying goes—including efforts to ban books. The free speech advocacy group PEN America noted that Texas leads the nation in book bans, with 713 bans enacted across 16 school districts, according to an analysis released in April. Last November, Texas governor Greg Abbott described certain books, particularly those related to LGBTQ+ issues, as “pornography or other obscene content,” and he directed state officials to develop standards to bar such books from K-12 public schools.

Given that literature is under fire in the state, university librarians are especially unlikely to give up tenure as they face heightened scrutiny from state officials, said Michael S. Harris, a higher education professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and director of SMU’s Center for Teaching Excellence, who also serves as chair of the Department of Education Policy and Leadership.

“Right now, it is an everyday occurrence that librarians in this state are being attacked. And that has primarily been at the K-12 level. But it doesn’t take a huge leap of logic or imagination to think that that could potentially happen in our state institutions,” Harris said. “I think this is exactly the wrong time to be having this conversation given the political realities of the state right now.”

Harris said it’s hard to determine how common tenure is for librarians, but it’s not unusual. And arguments for librarians having tenure mirror those supporting tenure for all scholars: that they need academic freedom to perform their jobs and a voice in institutional governance.

Harris noted that a decision was made, at some point, to give librarians tenure at Texas A&M. So, what changed? If they needed tenure at one point, why don’t they need it now, he wondered.

“Looking around at what we’re doing to libraries in the state, I cannot think of a worse time to potentially lose the protections of academic freedom and tenure,” Harris said.