You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

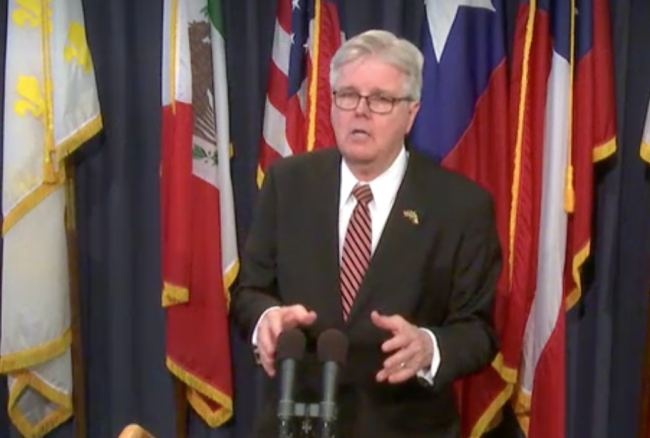

Texas lieutenant governor Dan Patrick proposes to end tenure during a news conference Friday.

The Texas Senate

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick of Texas said Friday that he would see to the end of tenure at the state’s public colleges and universities. His reason? The University of Texas at Austin’s Faculty Council had recently gone “too far” in asserting professors’ right to teach critical race theory.

“What we will propose to do is end tenure, all tenure for all new hires,” Patrick, a Republican, said during a press conference. For currently tenured professors, he continued, “the law will change to say teaching critical race theory is prima facie evidence of good cause for tenure revocation.”

It’s unclear how far Patrick’s proposal will go. Texas lieutenant governors have real power when it comes to setting the legislative agenda, and Patrick said he already has the support of Brandon Creighton, Republican chair of the state Senate Committee on Higher Education. Unnamed university leaders and members of the University of Texas system’s Board of Regents also “think tenure has outlived its time because they don’t have control of their own universities,” Patrick said. Even so, any serious attempt by Texas to end tenure will be a titanic battle between legislators and faculty advocates: PEN America has already called the proposal “a mortal threat to academic freedom,” while the American Association of University Professors fact-checked Patrick’s “disingenuous” speech and warned that changing the law to make teaching CRT a fireable offense is “an extremely dangerous authoritarian precedent.”

“In a democracy, politicians do not determine what people are allowed to learn or forbidden from learning,” Irene Mulvey, AAUP president and professor of math at Fairfield University, said in a statement.

Escalation of Conflict

What’s certain is that the ongoing war on CRT escalated significantly with Patrick’s announcement. The move didn’t necessarily shock those who have been tracking legislative attempts to ban the teaching of CRT or other so-called divisive concepts this legislative session, however. Whereas earlier anti-CRT bills mostly targeted K-12 instruction, these experts said, 2022 is much more about higher education.

Sumi Cho, a retired DePaul University professor of law who taught a seminar on critical race theory, said, “Throughout 2021, we saw what I’ll call the White Discomfort Bills 1.0,” which largely mimicked the former Trump administration’s now-rescinded executive order against the teaching of divisive concepts on race and gender in federal contractor trainings. In early 2022, Cho continued, “we’ve seen an explosion both in terms of quantity of bills, as well as the severity of the language.”

Cho, who serves as director of strategic initiatives at the African American Policy Forum—the group that co-wrote the template resolution on CRT that UT-Austin’s Faculty Council adopted, offending Patrick—said bills in six states sought to ban the teaching of CRT by name in 2021, compared to 25 explicitly targeting CRT and systemic racism this year. Idaho, Iowa and Oklahoma enacted divisive-concepts laws for higher education last year, but some 20 states are targeting colleges and universities this year, she added.

As of Friday, 23 states were considering 49 different divisive-concepts bills implicating higher education, according to tracking by PEN America. Many include penalties for violations.

Regarding these penalties, Cho said mandatory punishments and private cause-of-action “vigilantism” are on the rise—inspired, no doubt, by the 2021 Texas law outlawing most abortions, which opens up those in violation to private litigation. Cho cited a bill in Oklahoma that would allow K-12 employees to be fired for failing to comply with a proposed ban on books involving sex, sexual "perversion" or sexual or gender gender identity, and for parents to sue and collect $10,000 a day if the offending book is not removed within 30 days. Another bill would allow K-12 employees to be sued for $10,000 for continuing to promote ideas shown to be “in opposition to the closely held religious beliefs of the student.”

A third Oklahoma bill, SB 1141, would ban college and university programs beyond gender and ethnic studies from including in any required course “any concepts related to gender, sexual, or racial diversity, equality or inclusion.”

Cho said legislators are also broadening their takes on divisive concepts, to include religion, culture, political beliefs and LGBTQ issues this year.

Against ‘Ideological Coercion and Indoctrination,’ and Funding as a Tool

In South Carolina HB 4605 seeks to protect individuals from “ideological coercion and indoctrination” by any state-funded entity, including postsecondary institutions. This includes private colleges that accept state funds. Under this proposed law, no such entity may “subject” anyone to defined divisive concepts about race, gender, religion or sex, or compel any individual to accept or adopt the following: the existence of genders other than male and female and gender fluidity; nonbinary pronouns, honorifics or related speech; unconscious or implicit bias; or that race and sex are social constructs. No one under 18 may be taught about sexual “lifestyles,” among other topics. Violations, to be reported to a state hotline, lead to a loss of state funding, tax-exempt status and “any other state-provided accommodation or privilege,” until the entity demonstrates compliance. Beyond HB 4605, two other bills seek to limit discussions around race and other topics in South Carolina.

In Georgia, faculty members are already dealing with unpopular changes to public universities’ posttenure review system and the imminent appointment of higher education neophyte Sonny Perdue as chancellor of the University System of Georgia. Now professors are facing two divisive-concepts bills that mention postsecondary education and a legislative inquiry into such concepts.

In an initial, 11-page letter to the university system, David Knight, chair of the Georgia House Appropriations Subcommittee on Higher Education, asked for detailed information on diversity, equity and inclusion programs and DEI spending on each campus for the last five years. The letter asks about everything from whether faculty and staff members may include research, service or scholarship about diversity as part of their performance evaluations to professional development, “e.g. faculty support center hosting a book study on Ibram Kendi’s How to be an Anti-Racist.”

In an updated letter sent to the system last week, Knight pared down his request, saying, “I did not realize the volume of data my request would produce, and I appreciate your feedback on this matter,” suggesting some quiet back-and-forth with acting chancellor Teresa MacCartney. Knight continued, “My motivation is to understand how university and college resources are expended, especially as it relates to helping students earn degrees on time, in high-demand fields, with as little debt as possible, or otherwise related to improving the economic opportunities of Georgians and Georgia.”

Knight said he now wants an organizational chart for each institution that had programs or offices primarily or mostly involved in advocacy for “affinity or identity groups,” social justice, antiracism and DEI, and information on how DEI factors into to hiring and employee evaluations practices.

Heather Pincock, associate professor of conflict management at Kennesaw State University and a member of the United Campus Workers of Georgia, said Knight’s request can be read multiple ways, including as information-gathering ahead of the passage of any actionable anti-CRT law this year. Pincock said she was more inclined to see the request as data for state budget building, especially given Knight’s multiple statements of concern about increased university spending on DEI.

“My interpretation is that it’s a different strategy for trying to censor our campuses,” she said.

Pincock added, “What’s especially alarming about Representative Knight’s request is that while the [pending state] bills primarily target the curriculum and what is taught in the classroom, this request suggests that legislators are also interested in curtailing activities outside of the classroom, including student services.”

Dustin Avent-Holt, an associate professor of sociology at Augusta University, said that while DEI is being framed in part as a budgetary issue, “we’ve been experiencing budget cuts over the last 20 to 30 years in Georgia. And so [the Legislature is] kind of cutting us off, if you will, creating a kind of financial crisis and then using that as a pretext for getting rid of things that they don’t want to have at the university.”

Asked how he’d be affected by any new state law limiting the discussion of divisive concepts, Avent-Holt said, “I teach social inequalities. I don’t know how to teach about social inequalities without discussing that.”

Tenure in Texas

Texas passed an anti--CRT bill impacting K-12 education last year, which Patrick mentioned Friday during his press conference. That bill and others like it led Cho’s policy forum and the AAUP to co-sponsor a template resolution for faculty senates affirming the right to teach CRT and gender justice without political interference. UT Austin is among about a dozen institutions where faculty governance bodies have passed a version of that resolution, but so far it’s the only one that’s prompted a governor or lieutenant governor to resolve to end tenure.

Patrick said during his press conference that instead of passing a resolution on teaching CRT, UT Austin faculty members should have asked for an appointment to discuss the matter with him or other lawmakers, “because let’s be very clear, on the Senate bill that we passed on critical race theory, and the House bill that we passed, we didn’t say, ‘You don’t talk about race.’ We didn’t say that you can’t teach about slavery. We didn’t say that you ignore our history. What we said is, ‘You’re not going to teach a theory that says we’re going to judge you when you walk in the classroom about the color of your skin’ That if you’re white, you were born a racist.”

Experts say critical race theory isn’t assigning blame based on skin color but about recognizing institutional racism where it persists, including in the legal system. Faculty members generally consider the curriculum to be the purview of the faculty, and many if not most would consider involving legislators in curricular discussions—particularly those involving politically contentious issues—to be anathema to academic freedom.

Jeremy Young, senior manager of free expression and education at PEN America, said Patrick’s speech represented a “new low in attacks on education and academic freedom in higher education. The attempt to end tenure completely in all Texas state universities and then to specifically to revoke tenure for any professor who teaches critical race theory is despicable. It is the exact opposite of academic freedom. Exactly what academic freedom was designed to protect against are these kinds of government incursions into faculty teaching and faculty research.”

Andrea Gore, Vacek Chair in Pharmacology at UT Austin and chair of the council’s academic freedom committee, said she was shocked that Patrick had even noticed a nonbinding resolution on academic freedom. Nevertheless, Patrick’s “actions and words make it clear that not only has he been waiting for an opportunity to do away with teaching race and social justice in public universities, he has also had tenure in the crosshairs. This resolution scraped off a thin veneer that was giving faculty a false sense of security about academic freedom in Texas.”

Taking this view, tenure is not so much a new front in the war on CRT as CRT is the newest battle in the longer-running political war on tenure.

She added, “Tenure gives the faculty protection and freedom to speak and conduct research in their areas of expertise, even if those areas might be considered controversial, and without fear of reprisal.”

Richard Lowery, an associate professor of finance at UT Austin and frequent critic of the academic left who has argued that critical theory and social justice are incompatible with academic freedom—and whom Patrick mentioned flatteringly several times Friday—said he did not support ending tenure, which protects “dissident” faculty members, too.

“The lieutenant governor has never reached out to me or spoken to me about higher education, aside from acknowledging me in the audience of one talk,” Lowery said. “Ending tenure just gives the activists who have taken over UT Austin one more tool to threaten and punish people who depart from campus orthodoxy, once the politicians no longer view this as a politically valuable football to play with and go back to neglecting their obligation to provide oversight of the university.”

Lowery said that “if anyone wants to get serious about really reforming higher education so we can get back to providing valuable learning experiences for students and performing evidence- and logic-based research, they know where to find me, but hardly anyone seems to care about this on either side.”