You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

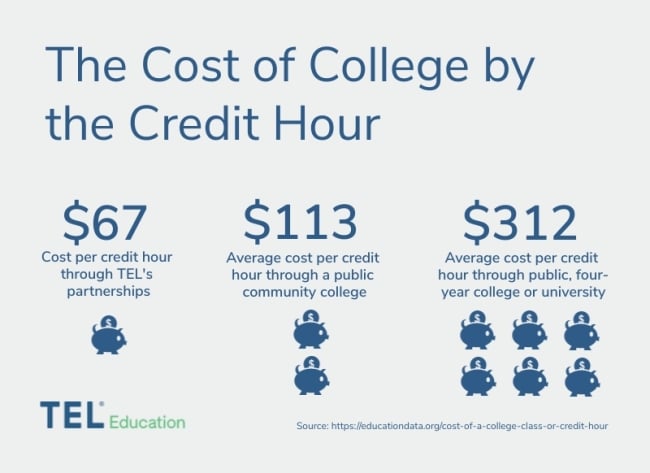

TEL Education courses cost significantly less than community college per credit.

TEL Education

An Oklahoma-based nonprofit offering online college courses and accompanying teaching support for $67 per credit hour—nearly half the average $113-per-credit-hour cost at community colleges—has signed up 32 regionally accredited partner universities in 15 states as it seeks to reach more students, many of them still in high school.

TEL Education’s 161 high school partners feed prospective students into the universities TEL works with after the learners complete dual-credit TEL coursework. Many of the high schools TEL targets are home to students who aspire to go to college but tend to lack the confidence or money to actually get there. Partner universities are drawn to the model because of the marketing support TEL provides and the opportunity to recruit students who otherwise would not know about their institutions or necessarily pursue college.

About half of the 32 universities working with TEL offer only dual-credit high school partnerships, while the balance also use TEL courses in their general education curricula. TEL courses are meant to scale, so while the software permits some customization, the underlying course is uniform, which keeps prices low.

High school students are charged $200 for a three-credit class. The fee is split equally between TEL and the college providing the credit. College partners pay TEL $99 per student enrolled. A spokesperson for TEL said many of its higher ed partner institutions have discounted credits by as much as 25 percent to reflect the savings TEL’s price tag affords them.

Many faculty members have concerns about a third-party online courseware designer supplying classes, because they worry such programs can lower academic standards and undermine their job security.

Alden Bass is a theology professor at Oklahoma Christian University, which has been using TEL to reach both high school students earning dual credit and students returning to college after dropping out. Bass said that when the TEL partnership was revealed to Oklahoma Christian faculty members 18 months ago, the announcement was met with great consternation.

“People were worried about job loss; people were worried about quality control and our name being attached to certain courses that we may not have vetted,” Bass said.

Concerns have since died down, he said, because many professors now recognize the partnership is “a way for us to stay competitive in a changing market” and is part of a larger effort to “standardize” online offerings.

Jonathan Rees, a history professor at Colorado State University at Pueblo and a member of the American Association of University Professors’ National Council, said such standardization is exactly the problem. Rees said he and many others at the AAUP have major concerns about online content designed by third parties such as TEL. Rees, who co-authored the book Education Is Not an App, said the AAUP is planning to revise its Redbook guidelines for academic practice to better reflect these worries.

“I find it really disturbing,” Rees said of the TEL model. “When decisions about content are made somewhere else entirely, I don’t think you’re getting the full faculty experience, so it really is a matter of academic freedom.”

Rees, who is also on the AAUP’s Teaching Committee, said faculty members should be in charge of their own course content, since teaching is “the reason there is a university in the first place.”

“Because of our educations and, in many cases, because of our decades of experience in the classroom,” Rees added, “we can help a university perform its core mission better with greater control over what gets taught and how it gets taught.”

A TEL spokesperson said faculty members at all TEL university partners review courses before they are approved.

Other online education providers similar to TEL are mostly for-profit and often feature a different credit-transfer structure.

For example, StraighterLine is very affordable, with a $99 monthly subscription model, but unlike TEL, it relies on transferring credits to one of its 130-plus partner colleges or to additional schools, which are not guaranteed to accept credits approved by the American Council on Education. TEL partners with regionally accredited universities, which its leadership says means credits are more broadly transferable.

Burck Smith, founder of StraighterLine, disputed the notion that its transfer structure is more limited. He said it’s always up to the individual colleges to grant credit, and it can be difficult to determine whether they will accept credit from another regionally accredited college as an elective or core class or for full or partial credit. Because StraighterLine works with such a large network of partner colleges, 97 percent of StraighterLine students have successfully transferred their credit, he said. He added that StraighterLine offers tutoring and ebooks for free.

Today, about 67 mostly general education courses populate the StraighterLine portfolio. Smith said StraighterLine has evolved since he founded the company 13 years ago and now offers universities customized partnerships. Much of this business has focused on accommodating adult students returning to school after a long time away.

If those students were to re-enter college and pay standard tuition directly to a school, instead of through StraighterLine, and then not succeed, they would forfeit the tuition they paid up front, and “they’d have a black mark on their transcript,” Smith said. The same is not true at a StraighterLine, because as with other alternative prior credit transfers, students can choose to “only transfer success”—meaning only the courses they passed or did well in, Smith said. That flexibility also protects future Pell Grant funding, which failing students can lose.

A more recent entry into the space is Outlier, a for-credit offering from MasterClass co-founder Aaron Rasmussen. Outlier recently forged a five-year deal with the University of Pittsburgh to ensure credits transfer the same way as TEL’s, through university partnerships. The controversial deal with Pitt has been subject to intense scrutiny by the Faculty Senate. Outlier is more expensive than competitors, at about $400 per course. (Note: This paragraph was updated to reflect a correction about the deal between Outlier and the University of Pittsburgh. It originally stated that the deal generated scrutiny by the Pennsylvania state legislature when in fact the scrutiny was by the university's Faculty Senate.)

Saylor Academy, a nonprofit like TEL, launched in 2008 and offers nearly 100 free and open courses at the college and professional levels. Southern New Hampshire University and Western Governors University, among others, accept Saylor credits for transfer. However, the Saylor Academy website is clear that because it is not an accredited institution, “some of our courses are explicitly connected to college credit opportunities; most of our courses are not.”

TEL executive director Rob Reynolds said 26 general education courses and three science labs are now included in TEL’s course catalog, which is designed to jump-start students’ college careers.

“Let’s say you’re 75 miles from the closest community college, and nobody in your family has gone to college before,” Reynolds said. “The idea of college is not even on the radar.”

For many universities, Reynolds said, the lure of TEL is to “expand the reach of your university, reach new counties that you’re not in,” by cultivating future students while they are still in high school.

Reynolds, a former language professor turned educational technologies entrepreneur, said TEL’s courses are designed for asynchronous learning and fit the general education curriculum at most regionally accredited institutions, the schools with which TEL mostly partners.

Richard Garrett, chief research officer at the higher ed research and advisory firm Eduventures, said many students hope to save money by knocking out general education courses on their own while also seeing if they can manage college-level courses without putting tens of thousands of dollars on the line. But Garrett said that too often students find they get what they pay for.

“There’s a tension between maximizing affordability and maximizing engagement, support and multifaceted learning models,” Garrett said. “Many high school students, particularly those that are more worried about affordability generally, will tend to struggle in a 100 percent asynchronous, online, self-paced environment.”

Many TEL partner universities are smaller regional or religious institutions with missions focused on reaching and empowering first-generation college students. These institutions also often want to become better known in their states and regions.

DeWayne Frazier, provost at Iowa Wesleyan University, said his university, the oldest in Iowa, began partnering with TEL about 18 months ago because it wanted students needing extra classes to graduate or to boost their GPA for athletic eligibility to have the opportunity to take self-paced courses over the winter and summer terms.

Faculty members have been supportive of the decision to work with TEL and voted unanimously in favor of it, Frazier said. Faculty leaders did not return calls and emails seeking comment.

“This is a recruitment tool and an enhancement tool more than a replacement-for-traditional-education-on-campus tool,” Frazier said.

Iowa Wesleyan has so far signed up two high schools from elsewhere in the state for dual-credit TEL classes. The high school students will be allowed to take a maximum of 15 to 30 credits using the TEL coursework and the Iowa Wesleyan logo. Frazier said the opportunity to build “brand recognition” is invaluable.

He said he has been impressed by the robust supports in place for students taking TEL’s self-paced courses. For example, algorithms are built into the program to alert student coaches to challenging course material, prompting them to check in with students having difficulty.

“Based on previous data, we know where students tend to struggle,” Reynolds said. “We’re trying to reach them before they ever know they have a problem.”

In a state like Oklahoma, where TEL has been working for some time, the company has already built an ecosystem of partner high schools and colleges in the state.

Reynolds said seeing such an ecosystem take shape has been heartening because students who may not have pursued college now are.

“They don’t have to get student loans to do anything,” Reynolds said. “We tried to figure out what true affordability really is—how much could someone save in three to four months and then take that first college course?”