You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As college leaders have increasingly accepted the idea that online education will be fundamental to their futures, many of them -- believing they lack the up-front money or in-house expertise to launch and manage those efforts -- have turned to companies that provide digital instructional design, marketing, student support and other services.

The rise of those online program management (OPM) or online program enablement (OPE) companies has brought with it growing scrutiny. Some comes from college officials who believe institutions should "own" most of those functions themselves, and from government regulators and think tank analysts who question the large shares of tuition dollars the colleges are paying to outsource that work.

The companies, which are part of a global market that the technology research Holon IQ has estimated could reach $13.3 billion by 2025, are clearly paying attention. The most visible corporation in the space, 2U, was first out of the gate in 2019, publishing a "transparency framework" that was designed in part to answer critics' questions.

This week, two more online program providers took their own steps to reframe the conversation. Academic Partnerships, most of whose 50-plus higher education clients are regional public universities, published an "impact report" focused on its programs' low prices (a weighted average of $14,000 in tuition and fees for its mix of business, nursing, education and other programs) and boasting of a first-to-second-term retention rate in its degree programs of 83 percent.

And today, Wiley Education Services released its own "Partnership Outcomes and Transparency Report 2021" with a wide range of student outcome and pricing data that shows that "on average we're priced well below the market while driving above-average completion rates," said Todd Zipper, president of Wiley Education Services. "We believe we have a great story to tell, and this is a conversation we want to engage in with the folks in Washington and with our partners."

While the reports and data from Wiley and Academic Partnerships represent a step toward greater transparency, it's not clear they'll come close to satisfying the questions and concerns of college administrators and policy experts.

Joshua Kim, director of online programs and strategy at Dartmouth College (and an Inside Higher Ed blogger), said he was dismayed by how little the companies had revealed about their financial relationships with colleges, which is for many the subject of most interest and concern. Academic Partnerships said nothing at all about its financial arrangements, and Wiley provided just one intriguing piece of data: that the average share of the revenue it keeps for itself in its contracts with institutions is between 30 and 40 percent, which is quite a bit lower than the figure most critics assert.

"What I would like to have seen more of in these reports is actual acknowledgment of the criticisms of the OPM model, and efforts to take the critiques seriously," Kim said. "There's starting to be a stink around these companies, and if they don't start being open and transparent about the issues people are most concerned about, schools are not going to want to work with these folks and regulators will turn up the heat."

The Landscape

The temperature has already risen.

For-profit companies that provide services to nonprofit institutions -- from private student lenders to housing providers -- have often drawn scrutiny, and OPM companies are no different. But the attention ramped up after controversial for-profit college companies spun off nonprofit institutions but kept close relationships with those institutions, raising the hackles of think tank analysts.

In early 2020, two key Democratic senators wrote to five OPM companies expressing their concern that the for-profit providers' business practices "appear to undermine the best interests of students." Then, early this year, Congress's investigative arm, the Government Accountability Office, undertook a wide-ranging review aimed at understanding the market.

And while the Biden administration has not visibly signaled whether it will seek to impose new regulations on providers that help colleges take their academic programs online, several officials within the Education Department -- in their prior roles at left-leaning think tanks -- had questioned the wisdom of these arrangements and their benefits to students.

2U took the first step toward responding to the increased scrutiny with its transparency framework and its first transparency report.

"We do want it to be perceived as a call to action to the space," 2U's CEO, Christopher Paucek, said when it released the framework. "They all have their own stakeholders, and it's not my place to decide what’s right for them. But as the leader of, still today, the market-leading company with the largest footprint, I think we need transparency as an industry. I'll be surprised if others don't participate in some fashion."

It took nearly a year, but Wiley Education Services and Academic Partnerships -- two of the other biggest online program companies -- released their own reports within days of each other, without either knowing the other had such a report in the works. An undercurrent of both reports -- not in data but in rhetoric -- is that while the companies provide a range of services to their college and university clients, the institutions' leaders themselves retain "complete control" over such core academic and administrative functions as admissions and financial decisions, "all academic matters," and tuition setting, as the Academic Partnerships report puts it.

Critics like Kevin Carey of New America have often asserted to the contrary, blaming online program companies for high tuitions charged by many OPM-delivered programs. Carey's 2019 takedown of the companies said this: "If there’s a fifth wave of for-profit scandal on its way, the most likely candidates are colleges where OPMs threaten to seize control of their hosts, like the fungus that turns carpenter ants into six-legged zombies."

What’s in the Reports

The 14-page Academic Partnerships report, released last week, focuses on student outcomes and program cost. It notes that nine in 10 programs at its partner institutions are in "high-demand, critical workforce areas such as health care/nursing, business, education and technology," and that its students are overwhelmingly working adults. It boasts that a quarter of its institutional partners are minority-serving institutions, and that 83 percent of students in its clients' programs are retained from the first to second term. (Note: An earlier version of this paragraph incorrectly stated that a quarter of Academic Partnerships' clients were historically black colleges and universities.)

By far the most surprising information was about the programs' cost to students. Citing a survey it commissioned from Boston Consulting Group, Academic Partnerships asserts that its average degree program charges $14,000, and that its programs in key fields are about a third of the cost of the average program offered through a range of its competitors (it lists 2U, All Campus, Everspring, Helix Education, Keypath Education, Noodle Partners, Pearson and Wiley).

Academic Partnerships says nothing in its report about the nature of its financial relationships with colleges and universities.

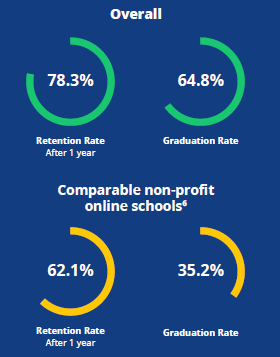

Wiley's 22-page report is dominated by data about the performance of students in its university clients' programs. It lists the retention and graduation rates for its graduate and undergraduate programs as 78 and 65 percent, respectively, and compares its' partners rates favorably with those at a set of "comparable nonprofit online schools," which clock in at 62.1 and 35.2 percent, respectively.

A spokeswoman for Wiley said the comparison group was "fully online programs" such as Southern New Hampshire University and Western Governors University that "enroll students similar to ours." Students at those institutions, like those in Wiley-supported programs, she said, "are accessing their programs online, are adult learners, and start classes at up to six different entry points each year."

But many if not most of the programs Wiley runs are with colleges and universities that are at least moderately selective in enrollment, while institutions like Southern New Hampshire and Western Governors are generally open enrollment, admitting all comers.

Wiley does share information -- though not many details -- about its financial arrangements with institutions. The page dedicated to partnership models notes that about two-thirds (68 percent) of Wiley's institutional clients choose a revenue-sharing arrangement (in which the OPM typically makes an up-front investment to launch the program and then takes a share of tuition revenues along the way) as opposed to a fee-for-service model, in which a college pays Wiley for specific services such as market research, enrollment services or faculty development.

It also includes the aforementioned data point that "on average, our revenue share is between 30-40 percent," and it compares the prices charged in its online programs in key fields favorably to those of competitors. Wiley-supported M.B.A.s, for instance, cost $25,591, while the competitive universe is $32,132.

Unlike with student outcomes, in which it compares itself to open-access programs like Southern New Hampshire and Western Governors, in pricing Wiley compares itself to all other online programs, which would include highly priced business programs at institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University ($141,320), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ($125,589) and the University of Southern California ($111,663). (Those data are drawn from Poets and Quants.)

Kim, the Dartmouth administrator, said he was surprised Wiley didn't provide more information about its revenue-sharing ratio, since it's lower than the 50 to 60 percent that many observers ascribe to these relationships.

When asked, Zipper of Wiley, in an email, acknowledged that a decade ago, the revenue share was "around 50 percent, and in some cases north of that," but that it had lowered the rate "due to competition and other factors … The market is correcting itself."

What’s Missing

More broadly, Kim said he believed that Wiley and Academic Partnerships could and should have spent more of their energy addressing financial arrangements and other issues that tend to raise concern.

The data on student outcomes that dominate the reports are "just not that interesting," Kim said, since "no one really expects that outcomes data [for these programs] will be any worse" than for other programs. "The world has moved on from this. That argument is old."

What hasn't faded are the questions about whether OPM relationships are good for institutions and students, and on those subjects, the reports are a "step in the right direction, but sparse," Kim said.

With a revenue sharing rate under 40 percent, Kim said, Wiley has a "potentially good story to tell, but they could have said a lot more, both recognizing the criticism as valid and explaining what they've done to get to this lower cost structure and allow colleges to keep more revenue."

"As is," he said, "I have a hard time believing it."

Stephanie Hall, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, which has closely scrutinized OPM contracts and urged colleges to "take control" of their arrangements with the third-party providers, reviewed the Academic Partnerships report but had not seen the Wiley report.

She said she viewed reports like these as "the companies’ effort to put out something that’s got some data behind it, to attempt to get out ahead of potential regulation that could be coming their way or even ward it off." Hall favors external regulation -- by the U.S. Education Department, accreditors or others -- of third-party providers like online program managers.

Hall expressed skepticism about statements in the Academic Partnerships report suggesting that online program companies play no role in academic decisions. She said Century's review of contracts showed some of them contain provisions that give the companies voting power on institutional steering committees that decide which programs to launch, for instance. And the contract between Academic Partnerships and Eastern Michigan University, she said, lists "program evaluation planning and course mapping" as one of the services the company offers -- functions that "challenge the claim that universities entirely control academic matters."

Zipper and Daniel Sepulveda, vice president for global partnerships and public policy at Wiley, said its first report was a beginning and that the company would release more and better information as it becomes available, including job outcomes and default rates for students in the programs they support. (They noted that much of that data is owned by the institutions themselves, not Wiley.)

"We support transparency -- we don’t want to be thought of as a black box," Sepulveda said. "We tried to respond directly to some of the questions that have been raised, and the data show that our students perform well and that if anything, we put downward pressure" on tuition prices.

Added Zipper, "We're signaling that we want to measure the things that can help us understand whether we’re providing value in the market. We think we are, and we intend to keep putting information out that can help show that."