You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

AAUP

Faculty influence in institution-level decision making declined in recent decades while faculty say in “local” decisions, such as those involving program curricula and personnel, increased. These are the top-line findings of a new national survey on shared governance by the American Association of University Professors, the group’s first such report in two decades.

‘A Mixed Bag’

About two-thirds (63 percent) of four-year institutions have no faculty involvement in budget decisions, for instance, signaling a reversal of progress on this front since the AAUP’s two earlier shared governance surveys, published in 1971 and 2001, respectively. For reference, 43 percent of institutions had no faculty involvement in budget matters in 1971 and just 13 percent had no faculty involvement in 2001.

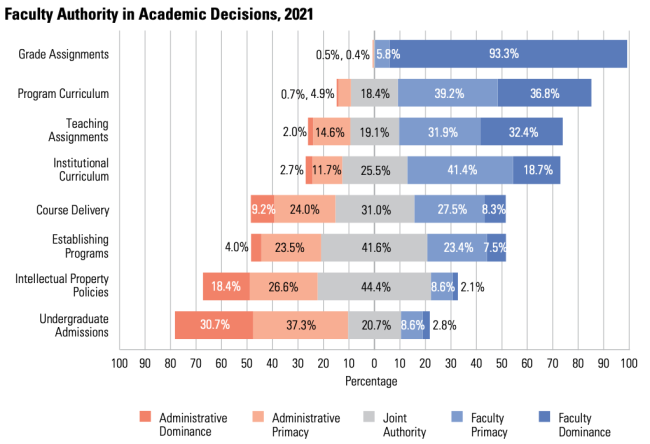

By contrast, faculty authority for things such as individual grade assignments is today a “faculty prerogative” at 99 percent of institutions. Program curricula were a matter of faculty dominance at 43 percent of institutions in 1971, 54 percent of institutions in 2001 and are today a matter of faculty primacy (a new survey category) or dominance at 76 percent of institutions.

By contrast, faculty authority for things such as individual grade assignments is today a “faculty prerogative” at 99 percent of institutions. Program curricula were a matter of faculty dominance at 43 percent of institutions in 1971, 54 percent of institutions in 2001 and are today a matter of faculty primacy (a new survey category) or dominance at 76 percent of institutions.

In another example of waning and waxing faculty influence, faculty members in 1971 appeared to have much more say in discussions about campus buildings and facilities than they do now. But today they have more say in who their chairs will be, tenure-track searches and even tenure decisions. In 1971, 20 percent of institutions -- meaning administrators, not the faculty -- exercised dominance over tenure decisions. By 2001, that figure was less than 2 percent. The figure today is still low, but it’s creeping up again, to 5 percent.

Some questions were new this time around, such as those pertaining to intellectual property policies. Two percent of chairs said the faculty exercised dominance in setting these polices. Forty-four percent of chairs said the faculty and administration shared joint authority, and 18 percent said administrators dominated.

“The overall results of this survey present a mixed picture of the current state of shared governance,” the report concludes. “At most institutions, faculty authority is consistent with AAUP-recommended governance standards in decision-making about programmatic, departmental, and institutional curricula; teaching assignments; and faculty searches, evaluations, and tenure and promotion standards.” Yet in the areas of budgets, buildings and allocations of faculty positions, the report continues, “the faculty has little or no meaningful opportunity to participate.”

Hans-Joerg Tiede, the AAUP’s director of research and author of the report, said this week that the AAUP’s widely followed standards on shared governance “don't call for just uniform faculty authority in every area.” Rather, he said, they expect different levels of faculty authority in different areas “depending on how closely they relate to the faculty’s primary responsibility.”

In areas such as the curriculum, promotion and tenure, the AAUP therefore hopes to see high faculty authority. Faculty say in areas outside of personnel and the curriculum may understandably be less, Tiede continued. But even as the AAUP doesn’t expect the faculty have control over budget issues, it does call for “opportunities to participate.” The AAUP has weighed in multiple times on the need for faculty involvement in decisions about financial exigency, in particular.

Over all, then, Tiede said, the findings are “a mixed bag.” Similarly, Tiede said, looking at the data from a historical perspective, “there has been lost ground in areas that relate to institutionwide decision making but improvements in more local decision making.”

Unionization, COVID-19 and Future Research

Unionization appears to have little influence on faculty power, even though some in higher education believe that faculty unions tend to weaken shared governance. Across 22 of 29 separate measures of shared governance, the AAUP found no significant difference between unionized and nonunionized campuses. Faculty authority was greater on unionized campuses in some of the 29 metrics, including salary policies: faculty chairs at 64 percent of nonunionized campuses said their administration dominated this issue, compared to 12 percent of chairs at unionized campuses. Teaching load data were parallel, in that 32 percent of chairs at nonunionized campuses said their administrations dominated on this issue, compared to 7 percent of chairs at unionized campuses. AAUP is both an advocacy organization and a union, with advocacy-only chapters on many campuses and unions on others.

For the report, the AAUP surveyed faculty senate chairs and professors who hold similar positions across a nationally representative set of four-year institutions. The sample was 585 chairs with a final response rate of 68 percent. Respondents rated the 29 different measures of shared governance on a five-point scale, from administrative dominance to faculty dominance. Joint authority was in the middle, representing a balance of faculty and administrative power.

For the report, the AAUP surveyed faculty senate chairs and professors who hold similar positions across a nationally representative set of four-year institutions. The sample was 585 chairs with a final response rate of 68 percent. Respondents rated the 29 different measures of shared governance on a five-point scale, from administrative dominance to faculty dominance. Joint authority was in the middle, representing a balance of faculty and administrative power.

Respondents were asked to think about shared governance prior to COVID-19. They were also encouraged to reflect on their institutions’ practices, not just their policies as written.

The AAUP previously released survey information on how chairs thought their institutions had responded to the pandemic, specifically, with respect to shared governance. Those results aligned with a separate AAUP investigation finding that shared governance had eroded on many campuses during COVID-19: about a quarter of respondents said that faculty influence at their institutions declined since March 2020. Twenty-four percent of chairs said they felt faculty members couldn’t voice their opinions about their institutions’ COVID-19 responses without fear of negative consequences. Perhaps more surprising was that 15 percent of chairs said that faculty influence increased over the same period.

Both the AAUP and other observers praised this approach -- leaning in to the faculty perspective during a crisis instead of cutting it off -- as an example of strong leadership that may promote greater innovation and agility through collaboration.

This newest report says a key question for future shared governance surveys will be “whether the pandemic had a lasting effect that resulted in a further deterioration in the faculty’s authority, particularly in institutional, as opposed to departmental, decision-making.”

Larry Gerber, professor emeritus of history at Auburn University and former chair of the AAUP’s Committee on College and University Governance, wrote the 2014 book The Rise and Decline of Faculty Governance: Professionalization and the Modern American University, arguing that U.S. higher education as we know it can’t survive without strong shared governance. Reviewing some of the new AAUP data, Gerber said he would have expected faculty authority to be in decline, not just due to COVID-19 but also the 2008 recession. He consequently said he was a “little surprised” that the AAUP found any increase in faculty say, even it was only at the local level.

In any case, he said, “I strongly believe that faculty primacy in academic decision making -- whether at the local or institutional level -- is crucial for maintaining the quality and integrity of American higher ed.” While faculty members may not always make “the wisest decisions,” he said, “they are far more likely to defend academic integrity and standards than are administrators and governing boards, who tend to focus more purely on a business-minded definition of the bottom line.”