You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

JamesBrey/iStock/Getty Images

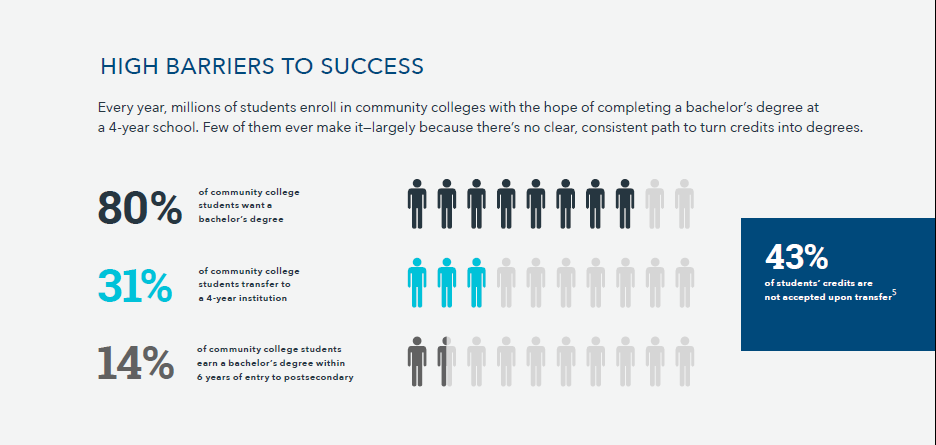

There's no shortage of evidence that what one might call the "transfer system" -- the web of processes and policies that allow students to move from one college to another and bring their academic credits along with them -- is badly broken in the United States. Barely one in seven community college students who set out to earn a four-year degree earn one within six years, and the typical student who tries to change colleges loses 43 percent of her credits.

Many factors contribute to these and other problems, including a lack of coordination and communication between and among institutions, and a commonly held view at many institutions that learning undertaken elsewhere is inferior. But most can be summed up by saying that, as is true of many aspects of higher education, transfer is more a spiderweb than a coherent system.

White papers, conference panels, even entire events (like this one Inside Higher Ed staged last year) have discussed efforts, undertaken and envisioned, to "fix transfer." When a coalition of nonprofit and advocacy groups convened a panel of experts as part of its Tackling Transfer Advisory Board in the spring of 2020, as the global pandemic and national recession were further scrambling the already chaotic flow of students, the conversation began, as so many do, with that goal.

But in one of the group's first discussions, one member, Marty J. Alvarado of the California Community Colleges chancellor's office, said she tried to "read the room" to see if she could sense where her colleagues were.

Letters to the Editor

A reader has submitted

a response to this article.

You can view the letter here,

and find all of our Letters to

the Editor here.

"It would be easier to maintain the status quo, to create a new program to add to the transfer chaos, add more counselors to help students navigate the transfer chaos, and call it a win," said Alvarado, the California colleges' executive vice chancellor for academic services. But tweaking the system wasn't the work that really needed to be done at this point, given the trauma that students already underrepresented in higher education were experiencing because of the pandemic, recession and national reckoning with racial justice.

Alvarado told her colleagues that she didn't think merely improving the current system was the work that really needed to be done at this point, and she asked if they were prepared to aim higher and go bigger. Were they willing to "reach beyond, to challenge ourselves?" she asked. The answer, overwhelmingly, was yes.

A year later, the result was "The Transfer Reset: Rethinking Equitable Policy for Today's Learners," a report out today from the Tackling Transfer Policy Advisory Board. The board -- whose work was coordinated by HCM Strategists, the Aspen Institute's College Excellence Program and SOVA, a nonprofit organization focused on transfer and student success issues, and funded by Ascendium and the ECMC, Joyce and Kresge Foundations -- ultimately issued a report that goes well beyond transfer. (Note: Some of the issues raised in the report have been discussed on Inside Higher Ed's "Tackling Transfer" blog, which publishes each Thursday.)

Diagnosing the Problems

The board's larger focus, like that of an increasing array of groups and leaders in and around higher education, is on ensuring equitable postsecondary outcomes for Americans no matter their background -- ever more important amid mounting evidence that those with post-high school credentials and learning fare better in the workforce, live longer and more.

"Attaining a living wage salary and important employment benefits such as health care and retirement often requires some postsecondary attainment, typically a bachelor’s degree. Life-changing advantages including improved health, stronger financial security and greater opportunities accrue to those who hold a bachelor’s degree -- and they benefit society as well," states the report.

Like other major policy statements crafted and issued in recent months, such as the Postsecondary Value Commission's attempt to redefine the worth of a post-high school credential, the transfer group's report makes racial equity central even more than it might have had it not been developed in the wake of last summer's tumult over racial justice.

"We … state the explicit aspiration that these recommendations will improve the acquisition and recognition of learning after high school for students from minoritized communities -- with a key focus on national evidence that the barriers to completion are particularly high for Black, Latinx and Indigenous students, and students from low-income communities -- to ensure they equitably receive credentials with labor market value, particularly bachelor’s degrees," the report says.

Addressing how students "transfer" -- or, to think about it in broader terms, accumulate learning experiences from more than one institution -- is especially important because underrepresented Americans are likelier than their peers to have their educational paths interrupted by finances, family obligations or other factors.

And "this trend is going to increase as students increasingly don’t take a linear journey," said Cheryl Hyman, vice provost for academic alliances at Arizona State University and another member of the Tackling Transfer board. "The way the world is changing, life circumstances are changing, there is a constant continuum of learning, and that means credits will have to be far more mobile."

The traditional focus on transfer is flawed and outdated in many ways, the report states.

Most state and institutional policies are still designed to reflect the assumption that students are moving linearly, mostly from a two-year to a four-year institution, but that is less true every day as workforce needs increasingly require people to update or broaden their skills.

Many students who change institutions lost significant proportions of the academic credits they've earned, and they spend time and money repeating courses, often delaying their progress in the workforce.

And many federal, state and institutional policies restrict financial aid in ways that limit the ability of older and working students to benefit from it; further, only three states have financial aid policies that specifically target transfer students.

Identifying Possible Solutions

The board's broad vision for a "modern, student-centered transfer system and a culture of learner agency" calls for ensuring that "all relevant learning is recognized and applied toward a major," that students throughout their learning journeys encounter policies that "recognize knowledge and skills acquired from many sources" (e.g., the military, workplaces), and that they are shown streamlined transfer pathways and transitions from high school through to the workforce.

Those lofty goals are made more practical through a set of recommendations focused on three areas: harnessing data for transformational change, maximizing credit applicability and recognition of learning, and advancing strategic finance and impactful financial aid.

Most of them are aimed at federal, state and higher education system leaders, with an emphasis on improving the information available to colleges and students on how institutions are faring in providing equitable access and attainment; aligning the standards institutions use to evaluate transfer applications and using technology that can smooth transcript exchange and course evaluation; and increasing or incentivizing financial support for transfer students.

The leaders of the Tackling Transfer group acknowledge that they have given themselves a tough task by widening rather than narrowing their focus and aiming for broad systemic change more than modest changes that might be more within reach.

But if ever there was a moment to go big, this is it, said Hyman of Arizona State.

"We're living in a time where our country has experienced a significant amount of hurt," she said. "We also have seen it bring a lot of people together who might not have come together in other times. There's an opportunity to capitalize on that -- people want to see other people do better."

The stakes are also going up for a failure to act, Hyman said. "The worse the problem gets, the more lives we hurt. We can't afford to be tweaking around the margins. I don’t think we can afford not to do this."