You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A “servants’ quarters” -- believed to have been used to house enslaved people -- stood on the campus of Virginia Theological Seminary until the 1970s.

Courtesy of Virginia Theological Seminary

Frances Colbert Terrell, age 78, grew up in Alexandria, Va., in the shadow of the Virginia Theological Seminary campus.

When she was a child, she would go to the campus to watch the boys from her community play baseball. In the winter she and her neighborhood friends went to a pond on campus to ice-skate.

“The white kids had skates,” recalls Terrell, who is African American. “We skated on our shoes -- just got out there and slid around the best we could.”

Terrell’s family has long-standing connections to the seminary, and she recently received a check for about $2,100 from VTS because of those connections. The money was part of a first round of annual reparations checks paid to descendants of Black people who worked on the campus during the Jim Crow era. Terrell's great-grandfather Daniel Simms worked as a waiter at VTS around 1910, according to the institution’s records. She said her late grandfather Frederick Douglas Johnson worked there, too, in the 1920s.

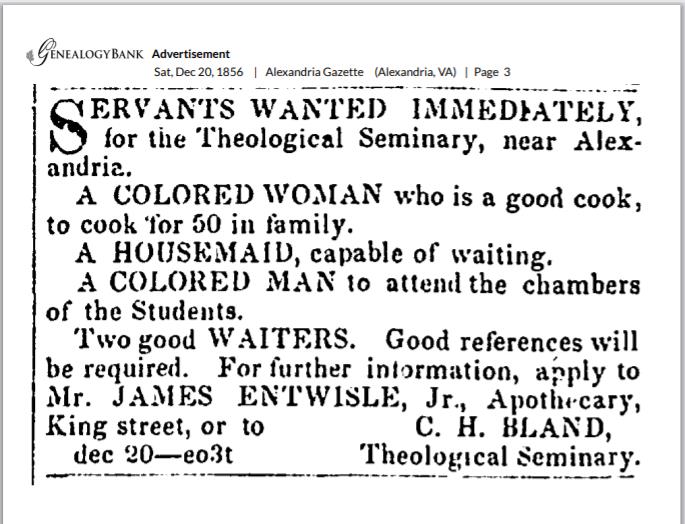

The seminary's reparations program, funded with a $1.7 million endowment established by the Episcopal seminary in September 2019, is one of the first of its kind, as The New York Times noted in an article about the program last month. The seminary is using income from the endowment to make annual payments to direct descendants of Black people who worked on the campus during the eras of slavery, Reconstruction and segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Terrell said her grandfather, a deacon of his church, would have been pleased by these developments and the notion of a nearly 200-year-old institution such as VTS making restitution for wrongs committed long ago.

“His words would be, ‘Well, praise the Lord, it’s about time,’” she said without hesitation. “Our community has been through a lot.”

VTS, founded in 1823, said in a 2019 statement that it “recognizes that enslaved persons worked on the campus and that even after slavery ended, VTS participated in segregation. VTS recognizes that we must start to repair the material consequences of our sin in the past.”

“This is the seminary recognizing that along with repentance for past sins, there is also a need for action,” the Very Reverend Ian S. Markham, dean and president of VTS, said at the time the endowment fund was announced.

Ebonee Davis, the programming and historical research associate for reparations at VTS’s Office of Multicultural Ministries, said the approach the university is taking toward the descendants, who are considered "shareholders" in the endowment, is to make straightforward amends without excuses or explanations for the institution's past actions.

Ebonee Davis, the programming and historical research associate for reparations at VTS’s Office of Multicultural Ministries, said the approach the university is taking toward the descendants, who are considered "shareholders" in the endowment, is to make straightforward amends without excuses or explanations for the institution's past actions.

“We did something wrong, we did something bad, there’s nothing that can change that,” she said in describing the approach, “and here’s a small token that will helpfully help us build a relationship in the future, and that’s it. No strings attached.”

Davis said the university has engaged historians and genealogists to identify Black workers at the campus and their descendants. The seminary has so far has identified 35 eligible descendants, from eight different families, and has distributed checks to 15 of those 35.

So far, all those who received checks are descendants of individuals who worked on the campus during the Jim Crow era, although the institution is conducting research to identify descendants of enslaved people who worked on the campus during the antebellum period.

“As we continue to research, we will hopefully find more shareholders so the amount will be divided amongst more people. If our research goes well, that number will stabilize as we find all the people that there are to be found,” Davis said.

The annual payment, about $2,100 this year, stands to fluctuate based both on the returns of the endowment and the number of shareholders identified. Davis said the seminary hopes to continue to grow the fund so that the per-person payment “won’t always be shrinking each time a new name is added.”

Curtis Prather, a VTS spokesman, said "significant contributions" have been coming into the fund, but its current value remains at around $1.7 million.

Many colleges have launched research initiatives to reckon with their historical ties to slavery, but relatively few have launched formal reparations programs of any sort. Among institutions with formal reparations programs, VTS may well be unique in issuing payments to the direct descendants of Black people who worked on the campus under conditions of slavery or segregation.

Princeton Theological Seminary, a Presbyterian institution, committed $27.6 million to an endowment fund supporting reparations in 2019, with the funds to be used for a variety of initiatives, including the establishment of 30 new scholarships for students who are descendants of slaves or are from underrepresented groups.

Georgetown University, a Jesuit university, committed in 2019 to raise $400,000 annually for a fund to support descendants of 272 enslaved individuals who were sold by the university’s founders, with plans to use the funds toward community projects such as health clinics and schools,

Virginia governor Ralph Northam signed legislation in March directing five public universities -- Longwood University, the University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, the Virginia Military Institute and the College of William and Mary -- to “annually identify and memorialize, to the extent possible, all enslaved individuals who labored on former and current institutionally controlled grounds and property” and to “provide a tangible benefit such as a college scholarship or community-based economic development program for individuals or specific communities with a demonstrated historic connection to slavery that will empower families to be lifted out of the cycle of poverty.”

Virginia governor Ralph Northam signed legislation in March directing five public universities -- Longwood University, the University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, the Virginia Military Institute and the College of William and Mary -- to “annually identify and memorialize, to the extent possible, all enslaved individuals who labored on former and current institutionally controlled grounds and property” and to “provide a tangible benefit such as a college scholarship or community-based economic development program for individuals or specific communities with a demonstrated historic connection to slavery that will empower families to be lifted out of the cycle of poverty.”

At VTS, Davis said it’s been a privilege to meet descendants and learn about their lives and those of their ancestors and how they have intersected with the seminary.

“It feels nice to work with these families so intimately,” she said. “I laugh and joke and cry with the shareholders. As we first meet and go over the paperwork, I get to learn their story. I know their ancestor’s story, or at least I know a part of it, when I reach out to them, and I get to hear more about it, but then I get to hear about them. They are who they are because of the sacrifices that their ancestor had to go through, and VTS is a part of that story -- unfortunately not in the best way. Not everyone’s singing our praises, and that’s OK, too.”

For her part, Terrell said she was “ecstatic” when she learned about the reparations program.

“This is something that had been talked about for years and years and it never came to fruition,” she said. “It’s not about the money or the amount of money. It’s about the fact that they’re recognizing what our folks have done for them -- the African American folks who worked there during that period of slavery and right after slavery. Most of them didn’t get any pay or very, very little pay.”