You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

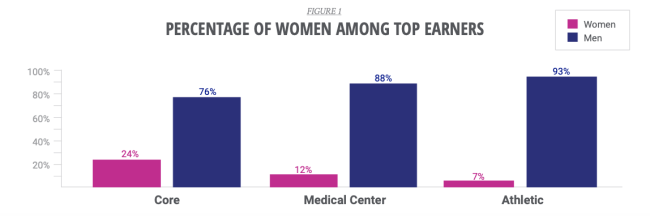

Percent of women among top earners at 130 top research universities

Women's Power Gap Initiative

Women are 60 percent of all professionals in higher education and have been earning the majority of master’s and doctoral degrees for decades. Yet women represent just 24 percent of the highest-paid faculty members and administrators at 130 leading research universities, according to a new study from Eos Foundation’s Women’s Power Gap Initiative, the American Association of University Women and the WAGE project. Women of color are even more grossly underrepresented, at just 2 percent of top core academic earners.

No Excuses

“Schools struggling to ‘find’ women and people of color for leadership positions should deeply examine their institutional cultures and seek to systematically change their hiring, retention and advancement practices to more quickly and urgently close the power and pay gaps,” the report says.

Women’s Power Gap isn’t strictly about higher education. It encourages pay and gender parity within corporations, too. But Eos and its collaborators say they focused this new report on academe because education “is viewed as the great equalizer, and institutions of higher education are considered moral exemplars for society.”

Colleges and universities are “role models for our future civic and business leaders, making diversity at the highest levels of leadership paramount,” the report continues. “These institutions have the clout to not only drive change within their own bodies, but to inspire action and motivate change throughout our country.” Put another way, higher education “could and should be the first to achieve gender parity and fair representation of people of color at the top.”

The groups' data parallel those from other organizations, including the College and University Professional Association-Human Resources' finding that women college and university administrators earn 80 cents for every dollar a man takes home, and that the gap isn’t shrinking significantly over time. Using federal data, the American Association of University Professors has also found that salaries for female full-time faculty members are 81 percent of men’s salaries.

The report is particularly timely, as the pandemic has disproportionately hacked away at female academics' research productivity.

What the Study Says

According to the Women’s Power Gap study, women are just about one-quarter of the most highly compensated core academic employees among R-1, or very high research activity, universities as measured by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions. Women hold just 12 percent and 7 percent of top-compensated positions within academic medical centers and athletics programs, respectively.

The total data set included about 2,300 employees. In general, the researchers were able to find through public information total compensation data for the top 10 earners at public institutions and the top five from private institutions. Data are from 2017 and the researchers note things may have changed since that time.

Women’s representation varies greatly by category, the report found. Women are 21 percent of presidents in the dataset, 34 percent of provosts, 34 percent of chief financial officers and 26 percent of deans. More than half (54 percent) of general counsels studied are women, but this is only about 4 percent of the data set.

Perhaps most significantly, women were just 10 percent of the top faculty earners within the data set of about 2,000 employees total, even as faculty members represented one-fifth of top earners over all. Many faculty members even held No. 1-earning spots as their institutions or were near the top, according to the report.

This “severe lack of women among the highest-pay rungs is essential to lessen the gender pay gap,” the authors wrote.

While women represent 50 percent of medical school students, they’re only 12 percent of top medical center earners. Top-paying positions were surgeons, clinical professors, department chairs and administrators. The majority of top earners in athletics are football and basketball coaches. Average compensation for head coaches of men’s basketball teams is 2.5 times higher than that for women’s basketball head coaches: $2.2 million compared to $830,000.

Women of Color ‘Nonexistent’

Women of color were “virtually nonexistent” among top earners at the subset of institutions that provided data on race, the study also notes, making up just 2 percent of this group. There were no female American Indians, Pacific Islanders or Alaska Natives in the group at all and just one man. Among men, Black and Hispanic men were also underrepresented, at 4 percent and 3 percent respectively, while Asian men were overrepresented at 11 percent.

“The data on women of color is particularly disconcerting because Asian, Black and Hispanic women have significantly higher educational attainment as compared to men in those groups,” the report says. “Black and Hispanic men, while still underrepresented, are four times more likely to be among the top earners.”

One of the most “surprising” statistics, according to the report, “is the minimal number of Asian women among the top earners,” or 51 men and just three women.

Men also tend to dominate higher-earning fields. Combined, business, economics and natural science, technology engineering and math fields account for 93 percent of the top-earning disciplines. This presents “a major equity issue needing bold, new systemic solutions,” the report says. “Much work has focused on getting women into STEM and business fields, yet, to achieve gender and racial parity among faculty pay in our lifetimes, we need to urgently look at the higher-level systemic bias within the market for faculty which, from a pay perspective, devalues fields that traditionally have more women and underrepresented minorities.”

Among other interventions, the report urges institutions to ensure that women and people of color are hired on at pay levels equivalent to white men. “Ban the use of salary history as a component of the interview process and for pay-setting,” the report says. “Ensure any pay negotiations do not result in unequal compensation.”

More than that, the report says, “Eliminate bias in all university processes and procedures -- hiring, advancement, and retention, among others. Conduct regular audits to root out unconscious bias. Hold staff and hiring committees accountable to equitable outcomes, not just hiring processes.” Some suggested check-ins: Are the demographics of the actual appointments proportionate to the diversity in the finalist pools? Or do efforts stop at getting women and people of color into the pools?

How Individual Institutions Fare

The report includes information on how each individual campus fares. Eleven of the 130 institutions studied have reached gender parity, with half of their top earners being women. One institution, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, tops this list, as women are 60 percent of top earners there.

Keith E. Whitfield, president of UNLV, said via a spokesperson that “diverse perspectives are essential to success in all facets of higher education. While there is still work to be done to improve parity at all levels of the university, we’re committed to equity in our hiring and promotion and we’re incredibly proud of the contributions that women in leadership positions make every day.”

At UNLV, eight members of the president’s cabinet are women, including the athletics director and vice presidents of student affairs, human resources, research, business affairs and government affairs. UNLV’s general counsel and chief diversity officer are also women. Five of these are women of color, according to information from the university.

Women are also deans in the College of Liberal Arts, College of Fine Arts, College of Education, School of Nursing, School of Dental Medicine, Graduate College, university libraries and the Academic Success Center.

Eight institutions, including Carnegie Mellon University, have no women among their top earners, according to the report.

Jason Maderer, spokesperson for Carnegie Mellon, emphasized that these data are from 2017, and said that women are now 20 percent of top earners on campus. The university continues to "expand the number of women in the ranks of its senior academic and administrative leadership roles," he added. Women are now three of seven vice presidents, two out of seven deans, and two of three vice provosts.

Arizona State University at Tempe and the University of New Mexico both have the most underrepresented minorities among their top earners, at 30 percent each.

Transparency, Accountability

The report underscores the importance of transparency and aggregate data surrounding pay. Specifically, it says, “release annual reports on the percentages of each demographic group within the highest earners (top 10, 20, 30), academic leadership (provosts and deans), and administrative leadership (the president’s cabinet).” Regular pay equity analyses are also a must.

Governing boards -- while not part of this particular study -- should conduct their own equity audits, the authors urge, as well.

Last, the report urges institutions to make “bold, long-term public commitments to reach equitable representation for women and people of color among the top earning university employees and do the same for each college, graduate school and academic center within the university.” Presidents should create annual benchmarks to work toward those goals, and boards should hold presidents accountable. Donors, in turn, should hold boards accountable, the report states.

Beyond campus, the report notes that 28 states now have equal pay laws. Both federal and state governments need to make clear that the aggregation of these percentages do not violate any personal privacy laws, it also says. And at the federal level, the secretary of education “should require public reporting of gender, race, and ethnicity of top earners at any university receiving federal dollars” and should publish that data annually.

Angela Onwuachi-Willig, dean of law at Boston University, said that women face a number of structural barriers to being considered for top-earning roles. Women tend to work in lower-paying fields within academe, as noted in the report. It’s well documented that women perform more service work than men, she continued, and as research is academe’s “coin of the realm,” service work tends to be rewarded with more service work -- not merit raises.

Women are also more likely to face a “second shift” at home in terms of caregiving than are men, Onwuachi-Willig said, potentially inhibiting their ability to be the kind of “ideal worker” that academe rewards. And they may be less likely to envision themselves in higher-earning leadership roles because of a lack of representation.

From the Mouths of Women

“There’s a saying, you can believe it if you see it,” Onwuachi-Willig said. “I never envisioned myself being in this role -- it was only because of people saying, ‘I think you should think about being dean.’ That’s a common thing among women.”

Even when they land potentially high-earning roles, women are less likely to negotiate for higher salaries and more resources than are men, Onwuachi-Willig said, noting that in her own work she’s always mindful of what she’s offered men who negotiate salaries and resources so that she’s sure she can offer the same thing to similarly situated women -- even those who don’t ask for more. This was something she picked up from a male mentor along the way, and while some might say it’s not “fair,” Onwuachi-Willig said she thinks it is.

“No one was advising me through the [negotiation] process and I didn’t know what to ask for for a good portion of my own career,” Onwuachi-Willig said. And even when women are savvy negotiators, “women have to be craftier when they do negotiate, because they can get a negative reaction when they’re strong or forceful.”

Data from the AAUP and other sources show that pay is more or less equal among assistant professors. So will the power and pay gaps close themselves over time? Those CUPA-HR data suggest they will not. Onwuachi-Willig said they won't, for all the reasons she mentioned.

Andrea Silbert, president of the Eos Foundation, also said Tuesday that “women have been earning the majority of bachelor’s degrees for 40 years, master’s degrees for 20 years and Ph.D.s for 15 years.” Yet, as women and people of color climb the ladder to the top, she said, “their numbers rapidly diminish due to a variety of factors, not the least of which is systemic bias in hiring, retention and advancement practices.”

Bold Goals

Silbert said university presidents therefore need to “set bold public goals for diversity in compensation and leadership and provide annual updates to hold themselves and their institutions accountable. They must bring down the systemic walls that are keeping women and people of color from the top year after year, decade after decade.”

Echoing Silbert, the report asks corporations and institutions to adopt systemic changes now. “The lessons of the last 30 years tell us that we will never close power and pay gaps doing more of the same programs, which largely train historically underrepresented groups to lead like white men. We need the diversity of lived experiences to improve our institutions and to rebuild our organizations, embracing disparate leadership qualities.”

The Women’s Power Gap Initiative plans to keep gathering these data, in the hope that it will see progress. One of the greatest challenges with this work is the lack of public data. “Without disaggregated diversity data at the institutional level, we are tilting at windmills,” the report says. But data are only one part of a bigger puzzle.