You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

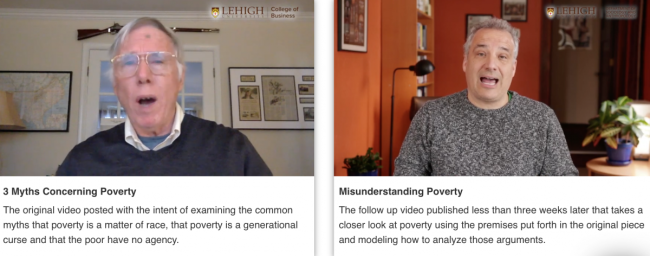

Frank Gunter, left, and Ziad Munson

Lehigh University

Lehigh University asked professors in its business school to advise the new Biden administration on their areas of expertise via short “kitchen table talk” videos. But one professor’s short talk on poverty, including its relationship to race, proved divisive -- and that the topic needed a more thorough analysis, the university said. So after temporarily removing the video for review, Lehigh reposted it alongside additional context from other scholars.

The outcome wasn’t ideal for anyone involved. The professor at the center of the controversy feels wronged by Lehigh, while some of his fellow faculty members are disappointed that the video was published in the first place. Many students feel hurt by the professor’s words. But the incident and the resolution do offer a potential framework to other institutions grappling with cases of similarly offensive speech: make room for and model academic critique, and be transparent about the process.

Frank R. Gunter, professor of economics, published his video to the Biden administration, called “Three Myths Concerning Poverty,” late last month. In the clip, Gunter explains that he wants to dispel the following “widely held” beliefs about poverty: that it is “mostly a matter of race,” that it’s a “generational curse” and that the poor have “no agency.”

Regarding the first point, on race, Gunter says it’s believed that “Blacks are poor and most poor are Blacks.” While this was the case as of 1940, he says, in 2019 there were “8.1 million Blacks below the poverty line, which is only 24 percent, which is only one-quarter of all the poor in the country.”

Gunter presents firm data regarding economic mobility to disprove the second point on generational poverty. Returning to shakier ground, Gunter then summarizes Brookings Institution research on "simple things" poor teenagers should do to join the middle class: finish high school, work full-time, wait until age 21 to get married and have children after marriage.

“Those three choices will pretty much eliminate your chance of falling below the poverty line in the rest of your life,” Gunter says in the clip. “If you violate all three rules, you have a 76 percent chance that you’ll end up poor … The idea that the poor are poor because of large economic forces, that they have no choice, that they have no options, is also a myth.”

Lehigh Responds

Soon after publication, Gunter began to face criticism from students and faculty members about his analysis. Among their questions: Why did Gunter discuss only African Americans and not other people of color with respect to poverty and race, and why did he refer to them as “Blacks,” instead of Black people, which is considered much more appropriate? Why did he not clarify that while Black people make up 24 percent of the American poor, they are approximately 13 percent of the general population? And why did Gunter present escaping poverty as a series of “choices” without addressing any of the barriers to exercising choice that poverty presents?

Students for Black Lives Matter, for instance, wrote on Instagram that “While it is important to have open debates on intellectual topics, the points brought up by Professor Gunter were not points of opinion, but incorrect and damaging statistics meant to put blame on impoverished people.” Calling Gunter’s statement’s “racist and ignorant,” the group said, “We don’t need a debate, we need action. Retract his statements, educate about why they were wrong and commit to anti-racism.”

In a lengthy post on his personal blog, Amardeep Singh, professor of English at Lehigh, wrote that Gunter’s video “uses data misleadingly, though the real source of the visceral reaction many students have had to his arguments probably comes from his language and rhetoric.” Gunter’s presentation “aims to suggest that government policies and systemic actions are less important than individual choice,” Singh added, while most historical evidence “would say the opposite: the reason poverty rates in the Black community have gone down has much more to do with changes in American law and public policy than changes in personal behavior: the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, affirmative action, and so on.”

Still, Singh said, “Gunter’s comments and my reactions to them should probably be seen as the beginning of a conversation, not the definitive endpoint. I would encourage both students and faculty at Lehigh to continue to have those conversations with one another -- respectfully.”

Several days after it was originally posted, Lehigh removed Gunter’s video. On social media, the College of Business wrote that it began the table talk series to “encourage discussion about pressing issues facing our society. When discussion ensures, we consider this a positive sign.”

Gunter’s post on the intersection of race and poverty engendered a response, the college said, and “we plan to post more videos with diverse perspectives on this topic. We want to encourage a full and open debate on these issues as this is a fundamental tenet of intellectual rigor and discourse.”

Soon, on a new webpage, Lehigh reposted Gunter’s video alongside a second video from members of the department of sociology and anthropology. Offering a brief timeline of events, Lehigh wrote that as “we listened to feedback from the community, including criticism regarding the selective use and manipulation of the available data which framed the findings with racist context, it was clear we needed to do more.” While Gunter’s original video remains, it said, “This new video takes a closer look at poverty using the premises put forth in the original piece and modeling how our colleagues who study sociology and anthropology would analyze those arguments.”

Ultimately, Lehigh said it acknowledged “that such a complex issue was not well suited to a brief single-viewpoint video. Our hope is that Lehigh Business can be a platform for more robust examination that encourages further learning on this topic along with the recognition of the need for disparate voices.”

In the new sociology and anthropology video, called “Misunderstanding Poverty,” Ziad Munson, department chair, says, “The arguments in the original video and the ones we offer here aren’t the only arguments. Indeed, people spend entire careers understanding the nuance of any one of our major points. However, we also want to be clear that not all views on a topic are equally valid if you apply standards of academic rigor.”

Further into the video, Heather Johnson, associate professor of sociology, contextualizes Gunter’s 24 percent statistic, saying, “there is a very substantial and well-documented relationship between race and class. If 24 percent of poor people are Black but the general population is only 12 percent Black, then this racial group is overrepresented among poor people.” Of course race is “just more than Black and white,” Johnson says, “but Black people in the United States are and have historically been disproportionately poor for many, many complex sociological reasons.” Various other members of the department offer sociological perspectives on poverty, and the new page includes links to research, data and additional discussion questions.

‘An Accurate Understanding’

Gunter said this week that he was surprised by the response to his video.

“Frankly,” he said, “I expected that the administration would channel Voltaire and say that they disagree with what I said but fully support my right to say it.” Instead, the video was taken down “without consulting me and only reposted with the interesting countervideo by one of my university colleagues that was arranged without my knowledge.”

Gunter said he’d hope to communicate that racism “certainly contributes to poverty in America but is not the whole explanation.” Regarding his point that Black people are 24 percent of the American poor, Gunter said he recognized that’s “much greater than the proportion of African Americans in the U.S. population. But it also means that three-quarters of the poor are not African American. In fact, a majority of the poor identify as white.”

In other words, Gunter said, “an accurate explanation of the poverty of almost 34 million Americans has to be more complex than racism against African Americans. And if President Biden’s administration is going to make substantial progress reducing poverty, then they will need an accurate understanding of its causes and trends.”

Gunter is vice chair of Lehigh’s Faculty Senate, which has pledged to host forums this semester to help the community understand poverty and race. Kathy Iovine, Senate chair and professor of biology, wrote in a memo signed by a group of fellow senators (not including Gunter), “Too many times statements are made in response to uncomfortable topics that do little to address the issue at hand. Perhaps it is (finally) time to do more than make a statement and move on.”

Academic freedom “allows for the original video message, and it also makes space for criticism about methods and conclusions,” Iovine also wrote. “In this instance, the faculty member presented data from a single racial group without analogous comparisons to other groups, and without placing such data within the broader societal context. As a result, the viewpoint presented dismisses racial inequities as a component of poverty and ignores institutional forces keeping people in poverty.” This has the consequence of “propagating ideas rooted in structurally racist ways of thinking.” It's “disappointing that the impacts of these deficiencies were not recognized, and that the video was instead promoted by our institution.”

Danielle Lindemann, an associate professor of sociology, appeared in her department's response video to discuss what she called the discredited "culture of poverty" argument that poverty is a failure of individual responsibility. She said this week that the two clips together "can serve as a teaching tool." Lindemann said she teaches about the faulty culture of poverty argument in her Sociology of Families course, for instance, so "it's useful for students to see that this is not just a straw man. These are arguments that people really do make, and that's one of the reasons why a sociological perspective is crucial."