You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Hannah Lua, Cortney Weintz, Joseph Pacec, Dhiraj Indanac, Kevin Linkac and Ellen Kuhl/Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering

Since colleges and universities announced last summer that they would be opening their doors to students, critics have argued that doing so was irresponsible and would lead to infections and deaths in nearby communities.

New peer-reviewed analysis released today in Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering suggests that, for some colleges, the link was indeed present.

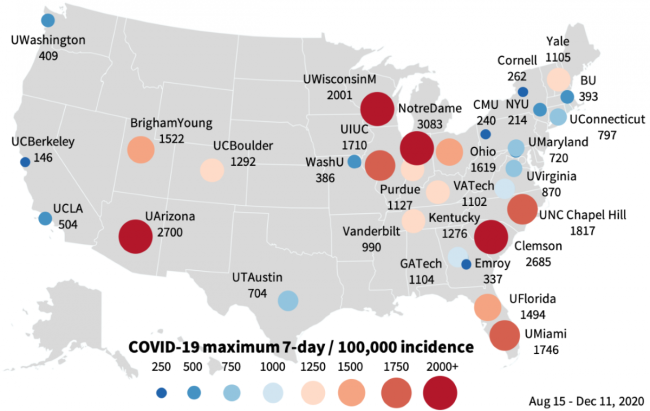

The analysis of 30 large U.S. universities indicated that in 18 of them, a peak in campus infections preceded a peak in the surrounding county by less than 14 days, suggesting infections were translated from the campus to the nearby community.

In some cases, the home counties of these large colleges had infection rates much greater than the rest of their state.

The research follows a study along similar themes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That research found when large universities opened for in-person instruction, their home counties saw a 56 percent increase in COVID-19 infections in the next three weeks, compared to the three weeks before the start of classes.

Similarly, an analysis from The New York Times suggested there may be links between university outbreaks and deaths in nearby communities.

There are of course limitations to this most recent study. Peaks in infection in the home county may have been linked to something else, such as tourism or a large event. Connecting county outbreaks back to campus ones usually requires robust contact tracing. And the 30 universities analyzed are not a representative sample of American higher education. All are four-year nonprofit universities; 19 of them are public and 11 are private. Only universities that updated case counts daily were considered for the analysis, likely skewing the research toward those that had resources to test often and keep up communications.

The 18 universities where a university outbreak was translated to a peak in the home county incidence within 14 days were Boston University, Brigham Young University, Clemson University, Emory University, Georgia Institute of Technology, Purdue University, University of Arizona, University of Connecticut, University of Colorado at Boulder, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Kentucky, University of Miami, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Notre Dame, University of Texas at Austin, University of Virginia, University of Wisconsin at Madison and Yale University.

Of course, in 12 universities, a campus outbreak was not translated to the home county. Those universities were: Carnegie Mellon University; Cornell University; New York University; Ohio State University; University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Los Angeles; University of Florida; University of Maryland; University of Washington; Vanderbilt University; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; and Washington University in St. Louis.

Links between campus outbreaks and community incidence have garnered concern, because although most students are not at high risk for severe complications from COVID-19, their older peers in a college town may be.

Universities that saw spikes showed themselves to be skilled at managing those spikes when they did happen, especially with flexible transitions to online learning, said Ellen Kuhl, chair of mechanical engineering at Stanford University and senior author of the study. But counties could not always follow suit.

“Campuses could manage this very well. So what they would do is just transition the instruction, they would isolate the students, they would find them because they would all do very tight surveillance testing,” she said. “But the communities would not. And so while the campus numbers reduced really quickly with the tight management of the disease, the counties had a much harder time to troubleshoot this and bring these high numbers down. Some of them never really did.”

What separates those universities where outbreaks spread to nearby towns from those where they didn’t is still unclear. Kuhl suggested that how connected a campus is to its community is one factor.

“Notre Dame is a campus where the entire community is the campus,” she said. “Everybody works on campus, everybody lives on campus.”

At Notre Dame, for example, by the end of the fall semester, 14.5 percent of students had been infected with COVID-19. At the same time, cumulative infection rate in St. Joseph County, where Notre Dame is located, was 7.8 percent, well above Indiana and national averages, “indicating that the initial outbreak at the University of Notre Dame had superspreading-like effects on its home county,” researchers wrote.

However, Notre Dame was able to contain the virus successfully after that initial outbreak by switching for a short period to online instruction. St. Joseph’s County was less successful in containing the spread, the report said.

Notre Dame has instead pointed to a different analysis, done by Dr. Mark Fox, a professor of medicine and public health at Indiana University.

According to that analysis, after Notre Dame brought back students, COVID-19 incidence in St. Joseph’s County increased by only “a fraction” of the CDC-suggested 56 percent, a university spokesperson said. And after students left for winter break, “infection rates increased in St. Joseph County -- which would point to spread unrelated to the university.”

Because of an agreement with the publisher of the Stanford study, Inside Higher Ed was not permitted to share the data with universities like Notre Dame before the publication of the paper. Officials at Notre Dame and other universities in this article did not have access to the findings of the report when they commented.

At the University of Wisconsin at Madison, a spokesperson noted that COVID-19 cases rose in every county in the state following Sept. 1, when students came to campus.

“As cases of COVID-19 continue at high levels across Wisconsin, UW-Madison remains committed to doing its part to keep transmission low,” the spokesperson said via email. “Despite a rise in cases early in the fall semester -- caught and contained quickly thanks to robust testing and rapid efforts to isolate positive students and quarantine those at risk of exposure -- campus experienced a low level of cases after the third week of September.” The university also provided 20,000 free tests to the general public.

Some universities have plans to do more testing or other mitigation measures this upcoming semester than they did in the fall. Wisconsin, for example, is planning to test all undergraduates twice weekly this spring, as some institutions, such as Colby College and the University of Illinois, did in the fall. Wisconsin, at the start of last semester, only mandated testing for those in certain groups, such as fraternities, but offered ad hoc and surveillance testing to other volunteers. (As part of its outbreak response, the university scaled up testing as the semester went on.)

Despite their findings in county data, the Stanford researchers did not conclude that reopening a university is a doomed endeavor.

“Taken together, our study suggests that it is possible for colleges and universities to reopen safely while controlling the spread of COVID-19. Successful reopening relies on limiting the introduction of the virus during the initial weeks of the term, regular testing and rapid tracing, and the collective understanding of the importance of quarantine and isolation,” they wrote. “With these strategies in place, our findings suggest that college campuses present a risk to initiate superspreading events, but, at the same time, should be applauded for their rapid responses to successfully manage local outbreaks.”

Beyond the links between county and campus data, researchers found that many of the universities had extreme incidence of COVID-19. Policy makers often consider a seven-day incidence of 50 cases per 100,000 people as a threshold for high-risk areas. All 30 institutions in the study exceeded that value. All but one exceeded the peak incidence of the first and second waves in the United States.

For 18 institutions, campus peaks fell between the first and second waves in the United States, when new cases dropped below 50,000 per day nationally, suggesting that they were unrelated to national disease dynamics.

“Instead, they are independent local events driven by campus reopening and inviting students back to campus,” authors wrote. “Our results are a quantitative confirmation of the common fear in early fall that colleges could become the new hot spots of COVID-19 transmission.”

By the end of the fall term, six institutions had seen more than 10 percent of their students infected. Notre Dame, UW Madison, BYU, the University of Florida and Kentucky all saw 15 percent or less of their students infected. At Clemson, 22 percent had been infected with COVID-19 by the end of the semester, meaning more than one in five.

The first two weeks of the term are also incredibly important, researchers concluded. Fourteen of the 30 studied institutions witnessed a peak in that time period.

The financial incentive for colleges to open has been clear. Room and board are often essential parts of a university budget, as is tuition, which could take a hit if students decide they do not want a fully online experience. The threat of lost revenue is particularly acute for four-year institutions, and especially private ones, a new report from the Brookings Institute concluded. Data from that analysis showed that four-year private institutions were the most likely to maintain in-person learning this fall.

Public institutions may have been less likely to be able to afford some of the measures and technology that allowed for in-person learning to take place at private colleges and universities, Brookings researchers suggested.

Because of whom these different institutions serve, low-income students were more likely to find their classes moved online this past fall. Online learning, especially for students who originally selected an in-person experience, can have negative effects on subjective well-being. Data from the Brookings analysis suggested that low-income students and Black students were more likely than other students to forgo college enrollment this year.

The results of the two studies illustrate the bind that many higher education institutions are in. For opening in person, the risks can be many. But the reward, for both a university’s bottom line and the happiness of its student body, can be persuasive.

“It’s possible to open a campus,” Kuhl said. “And we will see many campuses open.”