You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

William_Potter/Getty Images

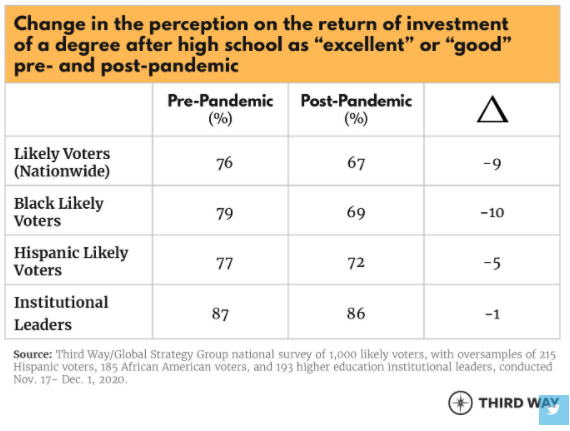

A national survey of likely voters shows that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a slight dip in the perceived value of higher education.

Third Way, a center-left think tank, and Global Strategy Group, a public affairs and research firm, surveyed 1,000 voters to get a sense of how the pandemic has affected public opinion of postsecondary education. The survey oversampled Black and Latinx likely voters, as well as institutional leaders. The confidence interval is plus or minus 3.1 percent.

Most survey respondents rated the return on investment of a degree after high school as "excellent" or "good" both before and after the start of the pandemic. But there was a slight dip. The confidence of all likely voters dropped by nine percentage points after COVID-19 struck (from 76 to 67 percent). Likely Black voters changed the most, by 10 percentage points (from 79 to 69 percent).

"I don't want to overstate this point because, on balance, a lot of people said it stayed the same," said Alex Ivey, senior director of research at Global Strategy Group.

A dip in trust in higher education is not really unique, Ivey said.

"It's part and parcel with the decline in trust of government institutions from the 1970s," he said, which is partly due to increased politicization of institutions, and partly due to runaway inequality.

Several themes emerged from the study. Many people (55 percent of respondents) believe college is too expensive for what students gain from it, which is a perennial response, Ivey said. But 50 percent of respondents also said the worsening economy is going to harm graduates' career prospects, which points to an overall more pessimistic view of what's happening.

Respondents also felt strongly about improving the value of higher education, said Tamara Hiler, director of education at Third Way. When asked to mark how important certain goals or policies for higher education are for them, likely voters focused on those that would improve affordability and access. The most important factor was making college more affordable to reduce debt, followed by ensuring that degrees lead to economic mobility and ensuring everyone gets a good value out of higher education, regardless of their demographics.

But affordability doesn't necessarily mean free, Hiler said. When asked to rate several policy options, making college free to all came in last. Providing degrees that increase socioeconomic mobility and supporting students who are working full-time were ranked most important to the respondents.

This is perhaps because respondents feel that higher education has not responded to the changing job market, said Angela Kuefler, senior vice president of research at the Global Strategy Group. Nearly 90 percent of respondents said the skills required for today's job market are quite different from a decade ago. The majority of respondents also believe that institutions can do more to support students and help them graduate, though they also believe that training certificates and bachelor's degrees pay in the end.

The survey results weren't surprising to Anguiano, particularly those related to how Latinx respondents felt. Latinx students faced completion gaps before the pandemic, and they also tend to have more financial obligations.

Still, while about half of Latinx respondents said a college degree is now less valuable, 72 percent said having a college degree provides a positive return on investment.

"It shows that Latinos are feeling the pandemic, but they still recognize the positive return that a college degree will bring," she said.

People might be feeling a larger trend. Bachelor's degrees are still worth the investment -- but not as much as they were a few decades ago.

"We’re sort of at a point in American society where many are experiencing the changing economy and in different ways," Anguiano said. "We’ve had stagnated wages for so long, yet the cost of college has increased over time. Financial aid buying power has decreased as well."

Leaders and policy makers should be concerned with the survey's responses from Latinx voters, as one-quarter said they view higher education in the U.S. unfavorably and nearly half of respondents said the value of a degree had gone down since the pandemic.

But Deborah Santiago, co-founder and chief executive officer of Excelencia in Education, said the long-standing trend of increasing Latinx enrollment in colleges shows that higher education hasn't completed lost this population's trust.

It may simply reflect the prioritization that many, especially Latinx people, had to do during the pandemic. People needed to get back into the workforce quickly. They had to pay bills and take care of family, she said. Giving up money to pay someone to get an education likely didn't seem like a logical option, she said.

Institutions need to work on raising awareness of financial aid and connect with the workforce to help students find ways to support themselves while in college, Santiago said.

"Institutions need to pay attention to workforce and economic needs as an access issue, not just a completion issue," she said. This could mean creating stackable credentials so that students can quickly get certificates to get better jobs and then parlay those certificates into associate or bachelor's degrees.

Colleges also have to reach out to these communities and students to show they support them. For example, Valencia College in Florida called each student to offer them support.

These data are an "important blip for consideration," but if the sector acts now, they needn't become a trend.

"You cannot take for granted that demography is destiny," Santiago said.

Wil Del Pilar, vice president of higher education policy and practice at the Education Trust, isn't surprised that Latinos are feeling hesitant about college. Six in 10 Latinos live in a household that has experienced job or wage losses since the pandemic started, he said. Nearly 60 percent of Latinos are essential workers and thus are likely deeply affected by the pandemic.

"This speaks to concerns around affordability, and the belief that the higher education system in the U.S. is ultimately not good," he said.

People of color over all may question the value of degrees because of the racist job market, he said. People of color feel they have to get more education to compete with white peers.

"You question the value of that degree if you’re burdened with a lot of debt and faced with less valuable opportunities," he said.

The largest difference between Black and Latinx and white likely voters in the survey is their definition of value. While everyone sees value as including the ability to pay off student debt and earn a decent wage, Black and Latinx respondents also see value as leveling the playing field for underrepresented minorities.

"They are more likely to agree that schools need to do more to help people fight a racially injust society," Kuefler said.

In short, "there are other things outside of earnings metrics that are important to communities of color," Hiler said.

Anguiano found it interesting that 75 percent of Latinx respondents said higher education should be reduce inequities, compared to 70 percent of Black respondents. Usually Black people feel more strongly about this issue, she said.

"It demonstrates that we’re in a very specific moment in time where Black and brown communities really want college to be something that provides more value than it has been in the past and to be an engine of mobility," she said.

Transparency is a key issue. Most disagreed that students have information about how universities spend their money, and just over half felt that students have the information they need on student outcomes. Unsurprisingly, institutional leaders felt the opposite.

"There's a disconnect between what institutional leaders believe they're doing and what the public believes out there," Kuefler said.

The majority of respondents want to require colleges to provide information on things like actual tuition costs, average graduation rates and the average amount of debt students graduate with. Fortunately, most institutional leaders said in the survey that they provide some information and are willing to do more.

And they need to do more, Kuefler said. When asked if these dips in trust will continue if nothing's done, she said they absolutely will.

"The dream of higher education still exists," she said. "I can't guarantee that the dream will stay if these changes that people are clamoring for don't happen."