You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

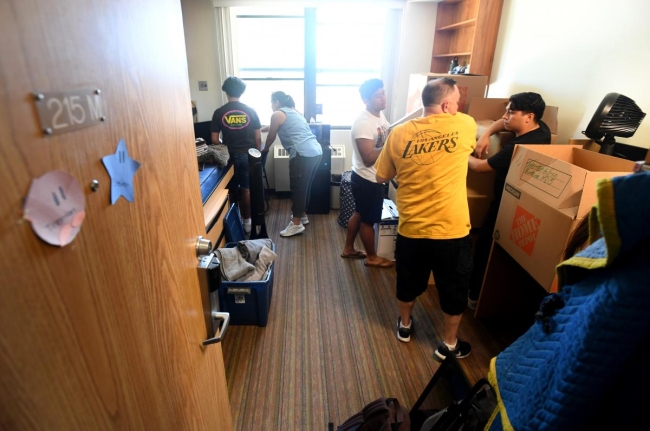

A new set of projections outlines how many high school graduates will be available to enroll at institutions like California State University, Long Beach.

Brittany Murray/MediaNews Group/Long Beach Press-Telegram via Getty Images

New projections released today showing more students graduating from high school than had been previously expected are good news for higher education, where traditional-aged 18- to 24-year-old students make or break budgets for many colleges and universities.

But they don’t change the outlook for a sector that has for decades relied on a steadily growing pipeline of students. Higher education will soon face shrinking cohorts of traditional-aged students, whose enrollment has long been key to making budgets balance. The sector may not be able to kick the can down the road and avoid fixing its creaky business model much longer.

“That good news really can’t escape demography,” said Patrick Lane, vice president of policy, analysis and research at the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. “There are simply fewer students available that were born in and after the Great Recession to fill college seats going forward.”

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, or WICHE, released new projections of high school graduates today showing a national peak of 3.93 million in 2025. It would be an increase from 3.77 million in 2019, if it holds true through pandemic-related disruptions.

It’s also an important increase from projections WICHE released four years ago anticipating a peak of 3.56 million in 2026. After the middle of the decade, though, graduation totals nonetheless go downhill. By 2037, the country is expected to produce 3.52 million high school graduates, according to the new projections.

One often-discussed fact adds an important wrinkle to these developments: high school graduates are diversifying fast. White students were 51 percent of the high school graduating Class of 2019. They’ll be 46 percent of the Class of 2025 and 43 percent of the Class of 2036. Meanwhile other student groups, particularly Hispanic students and students of two or more races, are making up a growing share of high school graduating classes.

That strongly suggests colleges and universities are going to need to increase their shares of students from groups that don’t traditionally enroll in large numbers if they hope to continue operating at their historic scale.

This picture is nothing new, according to those who work in and study higher education. But the fact that it’s reinforced by the new data brings the sector one step closer to key questions that will help determine its financial and operational future. Can it broaden access to large numbers of students from traditionally marginalized groups? Can it provide a welcoming environment that serves them well once they arrive on campus, rather than driving them away from it? And can it find a way to pay for doing so?

The question of broadening access isn’t as simple as a breakdown of high school graduates’ demographics would suggest. In addition to serving 18- to 24-year-old students, many believe the higher education sector must do a better job of serving adults and other nontraditional students, including those who dropped out of high school or college.

“We have disproportionate dropout rates that impact Latino, Black, Native American students at higher rates,” said Wil Del Pilar, vice president of higher education policy and practice at the Education Trust, a Washington, D.C.-based group advocating for equity in education. “We need to find on-ramps for those populations. Are there on-ramps for community colleges that we should be investing in so we can get more students up to that high school equivalency or some level of credential that will allow them to participate in an effective way and earn a living wage?”

Getting students on campus is one thing. Making campus a place where they can thrive is another -- whether that means scheduling classes at the right time for adults or finding a way to make the culture more welcoming of historically marginalized groups.

“They’re going to need to think about campus racial climate,” Del Pilar said. “Colleges are also going to have to do a better job of recruiting diverse students as high school graduating classes become more diverse.”

Many institutions have already found ways to serve different populations well. They are often addressing a host of issues not traditionally associated with academics: homelessness, food insecurity, childcare. Community colleges might hire social workers to help students from marginalized communities, said Vanessa Sansone, assistant professor of higher education at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

“It’s the institutions we overlook,” she said. “Those are the community colleges, the regional public four-year institutions and the institutions that are classified as minority-serving institutions. That includes not only Hispanic-serving institutions, which is a federal definition, but also historically Black colleges and universities and tribal colleges.”

Other colleges and universities can’t simply hope to steal strategies, though. In order to serve different student populations, colleges and universities will in many cases need to know those populations much better than they do today.

Individuals from the communities a college serves must be working at that institution, Sansone said. Staff members in many departments, from admissions to financial aid, often don’t reflect the students they’re trying to enroll. Diversify those offices and listen to the new hires seriously, she said.

How else would an institution truly understand its students’ needs? Take, for instance, the idea that Latinx students tend not to travel far to enroll in college, Sansone said. The reason is not necessarily the trope that Latinx students are too connected with their families to want to move for college. It might be tied to finances for a group that has been disproportionately hit by economic downturns. Or it could be related to specific histories in different communities.

“This particular community has been hurt and marginalized within all systems in the U.S., and education is one of them,” Sansone said. “So they’re going to be that much more reluctant to trust you if you don’t give them the respect and trust they deserve first.”

It might be tempting to think through these changes as affecting admissions first. The admissions department is the one that enrolls new students, after all. It is also the office at many institutions that has found a way to enroll the right mix of students to meet class goals while balancing budgets.

The latest set of projections shows that model to be untenable in the future, according to Angel Pérez, CEO of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

“I fundamentally believe institutions cannot solely rely on students for their revenue generation,” Pérez said. “We must diversify our portfolio if we are to be successful. The days of saying to chief enrollment officers that we have a budget gap, just bring us a few more students -- what the WICHE data is showing us is those days are over.”

The government will need to be more involved in funding higher education, he said. The way higher education finance works today, most institutions might very well want to do the right thing and open wide their door for new student populations. But many students underrepresented in higher education can’t pay to attend, meaning those institutions need to find new sources of revenue.

“My colleagues or chief enrollment officers have basically said we have plenty of low-income first-generation students of color and underrepresented students in our applicant pool,” Pérez said. “But there are only so many our institution can afford to take. Until we fix the problem of our financial model, we are only going to tweak around the edges of access.”

It's not entirely clear how the changes outlined in the WICHE data will affect the number of students who can pay for college. The projections don’t shed light on whether high-income families who can afford to pay more in tuition -- and are therefore often extremely important to college and university budgets -- can be expected to decline in number at the same rate as the overall pool of prospective students.

It’s also hard to say how the projected changes would affect any one institution. Individual results may vary based on a host of factors.

Nathan Grawe is a professor of economics at Carleton College and the author of the 2018 book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education (Johns Hopkins University Press), which sought to project future demand for different types of institutions. He found demand will likely differ for colleges depending on where they are located but that more prestigious institutions can generally be expected to fare better than less prestigious ones.

The latest projections support his analysis, he said.

“The Midwest and Northeast are obviously tougher regions,” Grawe said. “Institutions that are out West are going to continue to see a softer landing. I don’t think that necessarily means the institutions in the West can be ignoring the WICHE data. Even in the West, where it’s a rising trend, they’re going to experience that reversal in the 2020s.”

He was also struck by how uniform WICHE expects the high school graduation trends to be across different states. Generally, they peak in the mid-2020s and begin a long downturn through the end of the projection period in 2037.

Looking beyond the end of the WICHE projections, experts don’t expect growth in traditional-aged student cohorts to resume. Phillip B. Levine is an economics professor at Wellesley College who has written about “the coming COVID baby bust” for Brookings.

“We’re forecasting this additional decline in births because of COVID,” Levine said. “We think there is reason to believe that this is likely to be permanent or semipermanent.”

Time will tell whether the predictions bear out -- and whether the continued consensus that the unfolding changes are long term will breed adaptation, resignation or denial within higher education. It’s very easy for individual institutions to convince themselves that they are the ones that will beat the odds, even if everyone else is affected by large-scale trends.

Some, at least, find reason to hope the sector has come to terms with the need to change. They say it will still be a source of tension, though.

“For institutions of higher education, it’s only just around the corner that we see a significant tipping point,” Grawe said. “It’s clear that higher ed has recognized this already and has been working on this problem.”