You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

CCRC blog post

Students' incomes appear to have had major impacts on whether they continued at community colleges or left completely during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new analysis from the Community College Research Center at Teachers College of Columbia University.

The analysis, published in a blog post, used U.S. Census Bureau data that has been collected every two weeks since the summer from 100,000 random addresses. The researchers used the data from about 25,000 people who reported having community college plans, either as first-time or continuing students, for at least one person in their household from August through mid-October.

As of October, more than 40 percent of households reported that a community college student is canceling their plans. Another 15 percent are taking fewer courses or switching programs.

"Forty percent is a huge number of cancellations," said Clive Belfield, a research fellow with the center who co-authored the post with Thomas Brock, director of the center. "We would expect dropouts, but not to this scale."

It's also much different from what four-year colleges are experiencing. Less than 20 percent of those students reported they were canceling college plans, according to the analysis.

If the only deterrent was the safety of college, one would assume the rates would be similar, Belfield said. Instead, this shows that both safety and how the virus impacts different groups of people are factors in students' decisions.

Households with a community college student were more likely to report concerns about the coronavirus, such as catching it or having to care for someone who is infected, than households with a four-year college student. Community college student households were also more likely to say financial aid changes and affordability were major factors.

Community college leaders have been working to address the needs of students by providing remote services and additional resources, said Martha Parham, senior vice president of public relations for the American Association of Community Colleges. But it still makes sense that these students are changing their plans.

"Recognizing that community college students are older, are working, and have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, the enrollment decline makes some sense," Parham said in an email. "Many of our students are first-generation and are navigating the college admissions process remotely. Many of our students are parents that may be working at home and caring for school-age children who are taking classes at home. Many of our students work in industries that have been affected negatively by the pandemic. Students may not have the bandwidth -- literally and figuratively, to attend classes at this time."

Four-year college students were more likely to cite changes in course formats as a factor in their decision making. But when Belfield delved into the household data, he found these changes seemed to have a mostly positive effect on enrollment. He estimates that up to one-quarter of those students were retained because of the changes.

More than half of four-year college student households reported their colleges changed course formats, compared to one-third of community college student households.

"That’s a big difference, because it suggests that colleges are trying their best to keep students engaged and four-years have done better," Belfield said.

It's difficult to discern what changes were positive for students, he said, as the Census question isn't specific. He speculates it could be a variety of factors, from the availability of tests on campus to students' own risk tolerance, which could be driven by their income and access to health care. Four-year college students are also generally younger than community college students, so they may feel more sure that the virus won't be more than a bad flu for them.

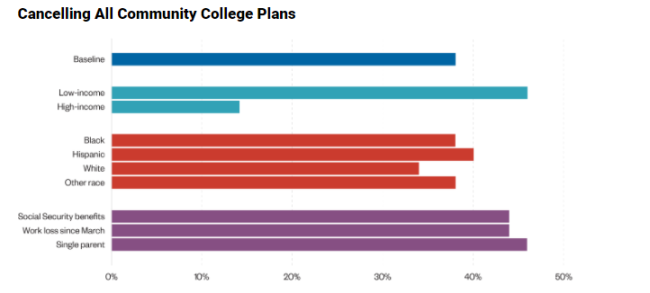

Equity gaps in the data are most apparent when looking at household income levels, he said. Low-income households were more than twice as likely as high-income households to report a community college student dropping out. Students who are also parents and those who have lost work since March are also much more likely to cancel their plans.

"The trouble with this is, low-income groups are going to come out of a pandemic with even fewer skills, so they're going to be in an even worse position than before," Belfield said.

Black and Hispanic community college student households were more likely to report plan cancellations than their white counterparts, but the gap wasn't as large as the gap between income levels. Close to 40 percent of Black households reported canceling plans, 40 percent of Hispanic households reported canceling plans and slightly less than 35 percent of white households reported canceling plans. Low-income households were also more likely to say that financial pressures were impacting community college plans, the analysis shows.

Robert Kelchen, associate professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, finds the enrollment patterns for community colleges right now puzzling.

Finances are clearly one of the strongest factors at play, he said. But it's concerning to see that so many of those who lost work during the pandemic are canceling plans, as those are the people who usually run to colleges in recessions, he said.

Policy makers could take actions to help with students' financial issues. The best thing they could do, though, is find a way to get the virus under control, Kelchen said.

Julie Peller, executive director of Higher Learning Advocates, said, "It just puts data behind what we all know: lower-income, working adults and student parents are being hit hardest and are needing to make difficult choices to stop or drop out of college during this pandemic in ways that some of their peers are not."

Peller isn't surprised by the analysis overall, but she was shocked at how many students canceled plans completely, rather than just cut back on courses. What worries her now is how colleges are going to re-enroll those students.

"There are systemic barriers within the system" for maintaining financial aid eligibility and transferring credits, Peller said. "Those complicated issues are, in non-pandemic times, difficult for students to navigate."

Policy makers will need to address those issues to get more students back to finish degrees. Institutions and policy makers will also have to continue addressing digital inequities at colleges to address the equity gap.

"I do think it sets us back, but I think it’s different from other times because we have these data and we can hopefully, with intentional policies, seek to not widen the gap further moving forward," Peller said.

Based on upcoming data from the Census, Belfield thinks spring enrollment is going to be just as bad as the fall. People need more financial support to enroll, and Belfield thinks the federal government should step in to offer something like the GI Bill for today's students. It could also offer more loans for students.

"The political will has always been what stopped us from making these investments, not the economic sense of them," he said.

The government will have to decide if it believes college is a good investment for the economy's future, he added.