You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center

The latest round of data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center paints a similarly dreary enrollment picture as previous reports.

The research center has been studying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on enrollment in higher education, producing a new report about every month this fall. The new numbers are based on 76 percent of colleges in the nation reporting as of Oct. 22. The previous report included 54 percent of postsecondary institutions.

Not much has changed between the two reports. Enrollments are still down over all for higher education -- by 3.3 percent. The decline was previously 3 percent.

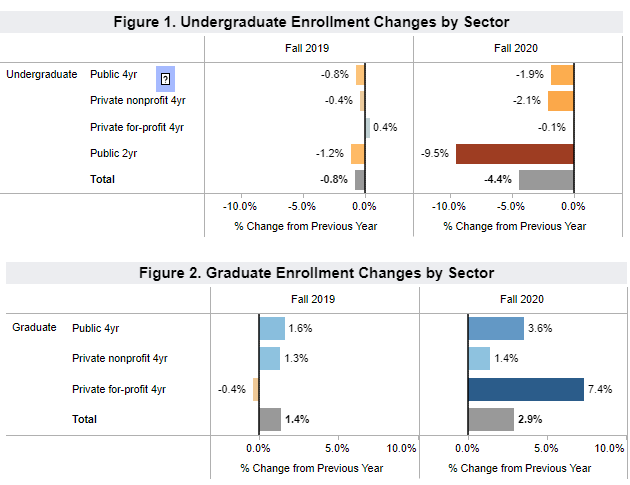

Undergraduate enrollment is also slightly lower in this report. Last month, it was down 4 percent. It's now down 4.4 percent. Graduate enrollment is up slightly from the last report, at 2.9 percent compared to 2.7 percent.

Freshman enrollment is still down, but less so than before. The decline is now 13 percent overall, compared to 16 percent in the previous report. Community college freshman enrollment also slightly improved, from a 23 percent decline to a 19 percent decline. Experts had previously said they expected community college enrollment to improve as the second eight-week term at those institutions started.

The report includes some more specific data on enrollments, as well. It has changes in enrollment for freshmen that can be broken out by sector and race or ethnicity, said Doug Shapiro, director of the research center.

The difference between freshman enrollment for underrepresented minorities and white and Asian American students is starker, he said. Black, Hispanic and Native American freshman enrollment is down by nearly 30 percent at community colleges. White and Asian American freshman enrollment is down by about 20 percent at community colleges.

Freshman enrollment at four-year institutions is down across all races and ethnicities, though Black freshman enrollment at public four-year colleges has not decreased as much as white or Asian American enrollment at those institutions. At private nonprofit colleges, white and Asian American freshman enrollment is down more than enrollment for underrepresented minorities.

"The divide is becoming more clear," Shapiro said.

The drop at community colleges in Hispanic student enrollment of 27.5 percent is especially concerning, he said, given that it was increasing greatly before the pandemic hit.

Across all community college students, not just freshmen, the difference among races is similar, though slightly less pronounced. Declines for underrepresented minority enrollment range from 19 to 23 percent, while declines for white and Asian American students are at about 15 percent.

For-profit colleges are still doing well with undergraduate enrollment, relative to other sectors, though it has decreased since the last report. The sector was up about 3 percent and now is down by 0.1 percent.

Some are concerned by the relative stability at for-profit institutions. Historically, these colleges pour money into marketing to and recruiting students, said Robert Shireman, director of higher education excellence and a senior fellow at the Century Foundation.

"That could be the beginning of some of the same kind of problems that we saw a dozen years ago," he said, referring to the influx of students, many coming from vulnerable populations, to for-profit colleges in the wake of the Great Recession.

Higher education over all is not seeing any enrollment boosts like it has in past economic downturns, Shireman said, likely because people are hoping to wait out the pandemic and return to their jobs.

But he's still worried that the tides could turn, even though several bad actors have closed their doors.

"If you look back 15 to 20 years, people were saying that the bad for-profits were gone, so we shouldn’t be concerned about growth at the for-profit level. Those for profits they were talking about were Corinthian, ITT Tech, the University of Phoenix. Those are exactly the institutions that grew too quickly," he said. "We’ve been dealing with the consequences ever since. The history and the incentives indicate that the for-profits that we have right now are in danger of becoming more predatory, and it can happen very quickly."

One notable piece of data is the split between part-time and full-time enrollment growth for for-profits. Part-time undergraduate enrollment is up nearly 7 percent, while full-time undergraduate enrollment is down 2.3 percent.

Shireman hopes this is an indication that people are trying out for-profit colleges before making a larger commitment.

"It might be a reason to not worry as much," he said.

Trace Urdan, managing director at Tyton Partners, an advisory firm, disagrees that a bump in for-profit college enrollments is indicative of predatory behavior. For-profits often operate on a larger scale, so they can spend more money on marketing and outreach, he said.

"The question comes in on whether students are making those choices fully informed," he said. "I do think those students know community colleges and what’s available there but still make a different choice."

For-profit colleges have stronger online programs than community colleges, Urdan said, which put them in a much stronger position during this pandemic.

Still, he's not seeing the same kind of countercyclical effect on enrollments as he did in the Great Recession.

"My sense is that's more about people not making big decisions in a pandemic," he said, adding that it's possible that having election results and getting accustomed to the new reality of life in the pandemic could drive more people to start making big decisions.

"I still think the for-profits will do better than the community colleges, but the community colleges will get some of that," he said.

Urdan doesn't disagree that student protections and enforcement for for-profit colleges are necessary, but he doesn't think people should be overly concerned about these colleges turning predatory due to a recession.

"It’s just people who don’t like those schools, and they see them doing well, and so they're inclined to think there’s a bad reason behind it," he said.

But he's still concerned about the same issue Shireman raised -- just from a different viewpoint.

The issue in the last recession was that for-profit colleges enrolled everyone who wanted to enroll -- without realizing that the job market didn't have enough room to hire all of those students later on, he said. These colleges were then judged on their employment outcomes.

"The thing I worry about, is that it requires an enormous amount of discipline to not enroll as many students as want to come," Urdan said. "That’s a very hard thing for a for-profit to do -- throttle their own enrollment because they’re trying to preserve the long-term value of their brand and the outcomes. Otherwise, we’ll have a second round of last time. And I don’t think the sector can survive that."

Despite having more data, it's still hard to say what next fall will bring. Shireman believes it will depend on the economy, a potential vaccine and how quickly things can return to a relative normal.

"The big decline in freshmen does suggest that there are a lot of people who have just delayed enrollment," he said. "That could lead to a much higher increase in enrollment … We may be in a situation, depending on how much Congress helps state budgets, where public institutions that have the capacity now will not in a year, and we’ll have a lot of those students end up at for-profits, which is what happened a decade ago."