You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

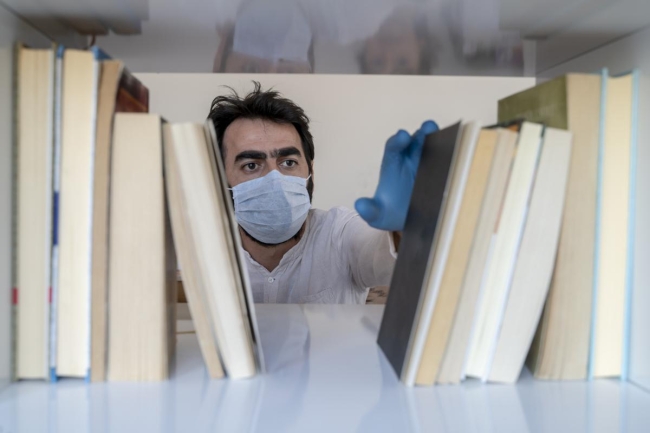

istock.com/CihatDeniz

In the run-up to exams and midterms, the library at Roger Williams University is often busy with students trying to borrow textbooks and squeeze in some last-minute studying.

Access to these materials is always limited because the number of textbooks available is small. But this semester, the imbalance between supply and demand is far worse than usual, said Lindsey Gumb, assistant professor and scholarly communications librarian at Roger Williams, a private liberal arts college in Rhode Island where students are back on campus this semester and participating in hybrid instruction.

As a safety precaution to slow the potential spread of COVID-19, librarians at Roger Williams are quarantining all returned print materials for 72 hours before making them available again.

The quarantining system is simple. When a book is returned to the library, a librarian wearing gloves and a mask places it on the lower shelf of a cart. The next day, the book is moved up a shelf. On the third day, the book is moved to the top shelf. The following day it is returned to the stacks.

An ongoing research project called Reopening Archives, Libraries, and Museums, or REALM, is investigating how long the COVID-19 virus survives on print materials, including hard and soft book covers and inside pages. The project is a collaboration between the OCLC, a global library collaborative; the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), an independent federal agency that provides grants to libraries; and Battelle, a nonprofit research and development organization.

Early REALM project testing found the COVID-19 virus was no longer detectable on materials stored in a lab setting after three days. When the materials were stacked, as books would be if returned to shelves in the library, traces of the virus were still present after six days.

The REALM project does not make recommendations to libraries about how to handle quarantining materials but is feeding its results to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In a presentation to the IMLS earlier this year, a CDC epidemiologist said that catching COVID-19 from a book is unlikely, but best practice would be to quarantine the book for at least 24 hours between lendings. Some institutions are quarantining materials for longer just to be safe.

For students who cannot afford their own textbooks and rely on the library to complete homework assignments and pass their exams, this delay is creating an untenable situation.

“We try our best to help students. We’ll look through the catalog and see if maybe another library has it,” Gumb said. “But we can’t help them if the book is in quarantine, and we are highly discouraging students from sharing textbooks.”

If students are unable to come up with the money to purchase their own course materials, Gumb offers to write to their instructor and explain the situation.

"Students are often embarrassed to tell a faculty member they can’t afford the book," Gumb said. "They don’t normally have to do that since they have access to one in the library."

There are around 40 textbooks available at the Roger Williams library, with typically no more than one copy of each title, Gumb said. The library did not purchase these textbooks. So-called desk copies of textbooks were given to the library by instructors, who received them from publishers when they assigned the textbook. The textbooks are cataloged as reserve materials, meaning students can only borrow them for a short period and typically cannot remove them from the library.

The library at Roger Williams, like many academic libraries, does not have the budget to purchase digital or print textbooks for students individually. Copies of textbooks sold specifically for use in libraries are often prohibitively expensive, Gumb said.

Many libraries are grappling with the same situation, said Nicole Allen, director of open education at open-access publishing advocacy group SPARC.

“The pandemic has intensified and exposed so many gaps and cracks in our society, and access to course materials is one of them,” Allen said. “Students are struggling. So are faculty, and so are libraries.”

Libraries that have built up print reserves of textbooks aren’t able to circulate those materials as they did before the pandemic, either because materials are being quarantined or because students can’t access their libraries at all.

During the spring, many publishers made access to digital course materials free to ease students’ transition into remote instruction. But that offer was temporary. At Santa Fe Community College, for example, students are still learning remotely and do not have access to print materials in the library.

Valerie Nye, library director at the community college, described her struggle to find a solution in a recent webinar hosted by the Association of College and Research Libraries. She described how her institution is now working with a company called BibliU to provide students with access to digital textbooks. She noted, however, that this is being funded by CARES Act federal stimulus funding and may not be a sustainable option for the library in the long term.

VitalSource, an e-textbook distribution platform, offered one of the most comprehensive programs for free access to digital textbooks in the spring. In total, 219,000 students from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, accessed free digital course materials from over 600 academic publishers through the VitalSource Helps program.

Since the VitalSource Helps program ended in May, many libraries have reached out asking for help, said Mike Hale, vice president of education for North America at VitalSource.The company typically works with bookstores rather than libraries, but Hale and his colleagues have been thinking about a possible solution to help librarians out and ensure all students have the course materials they need.

A rapidly increasing number of institutions are embracing inclusive access programs, where students are automatically billed for access to textbooks as part of their student fees, said Hale. VitalSource is currently in discussions with publishers to offer institutions a free e-textbook for library use as part of its inclusive access offer. But there is a catch. To qualify, no more than 5 percent of students can opt-out of the inclusive access program. This initiative, which is yet to be formally announced, would ensure low-income students still have free access to materials through the library, Hale said.

Allen and Gumb, who are proponents of open educational resources -- freely accessible and openly copyrighted course materials -- feel that this VitalSource offer isn't sufficient.

“It’s a Band-Aid on a much bigger problem,” Allen said.

In the future, Gumb said she will be stepping up her advocacy efforts for OER, encouraging faculty members to develop their own course materials or adapt existing materials to their own needs.

“I didn’t want to overwhelm them this semester, as everyone is already doing so much,” she said. “But I will be doing a lot more advocacy around OER as a long-term solution.”