You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

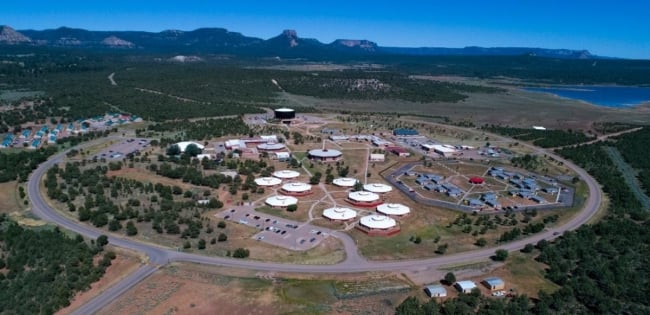

Diné College

Charles M. Roessel, the president of Diné College, was worried in June.

Summer enrollment at the tribal college in Arizona was down 60 percent. Fall enrollment was down 70 percent. And it was easy to understand why: the college serves the Navajo Nation, which was hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. The area where the main campus is located was hit by the virus even harder than the rest of the reservation.

"We started thinking the worst," Roessel said.

Then, a few weeks before the semester began, the college's phones started ringing. Diné was getting 200 calls per day from students. Fall enrollment landed at 1,348, just 75 fewer students than enrollment in fall of 2019.

Roessel is optimistic about the college's future, and it's because of these students, he said.

"I leave here at night sometimes, and I’ll see three vehicles in the parking lot," he said. Students will be seated out in lawn chairs with their laptops, sometimes with their own children on laptops next to them, working on homework using the campus's Wi-Fi. "With the resilience of the students, you can’t help but be optimistic."

Tribal colleges are facing many challenges as they continue to serve students during the pandemic and a recession. They're starting from a disadvantage, as they are typically underresourced compared to nontribal colleges. Their students, most of whom are Native Americans, are more likely to be low income. Internet connection isn't even possible in some parts of tribal lands. Many tribal colleges, and faculty members at those colleges, had no experience with online learning before COVID-19 hit the United States.

Yet they carry on. They took advantage of trainings. They're finding innovative ways to expand internet access. They're hosting traditional ceremonies online.

But they're going to need assistance to continue supporting students in robust ways, said Cheryl Crazy Bull, president and CEO of the American Indian College Fund. Higher education can't claim to be equity-focused without helping these institutions at the same time, she said.

"Tribal colleges educate around 10 percent of all Native American and Alaska Native students who go to college," she said. "Tribal colleges are vital to the equity issue."

Tribal colleges and universities are operated by the Native American tribes they serve. They receive funding through several pieces of federal legislation. Most tribal institutions offer primarily two-year degrees, though some also offer four-year degrees and master's programs. They teach students about Native culture and tradition, including Native languages, preserving them in the process.

Native American students who attend tribal colleges are more likely to graduate without debt, receive support and pursue careers that align with their interests compared to their peers who attend nontribal colleges, according to surveys. But tribal colleges lag behind in completion rates. The average graduation rate for two-year tribal colleges is just under 21 percent, and the average graduation rate for four-years is just under 25 percent.

Little Access, New Solutions

Access to technology is one of the largest hurdles for tribal colleges, many of which are in rural areas.

Tribal members define access to the internet differently from others, Roessel said. In a city, people would say they don't have access, but they can go to a library. His students say they have access -- they just have to drive 15 miles on a dirt road and hike to a higher butte to get a signal.

Many faculty members also faced a steep learning curve when they moved to online learning in the spring. Some faculty at Little Big Horn College in Montana, which is up in its enrollment this semester, used YouTube or Facebook Live in the beginning, but they realized it wasn't private, said David Yarlott, president of the college.

Over the summer, faculty received training from the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, he said. But connectivity is still a problem.

The college looked at providing hotspots, but one house can have up to seven families living together, which doesn't leave much bandwidth, Yarlott said. Some internet providers have offered to help, but sometimes that's impossible. Spectrum offered to provide connections, for example, but they don't service that area. Even with towers in the area, internet still can't reach the more mountainous regions, he said.

To help somewhat with access to technology, the college replaced its computers with new ones and gave the old ones to students so it doesn't have to track them.

Other colleges are luckier. Red Lake Nation College in Minnesota already had a virtual backup system for classes that it used on days with extreme winter weather, said Dan King, college president. Still, the college is in a remote location near the Canadian border. So it sent students technology suitcases for the fall.

Every student received a laptop, a cellphone with a hotspot and unlimited data, and a virtual reality headset. It helps that the college is small -- around 150 students, though that dropped to 122 this fall -- so $380,000 covered the bill. The Red Lake Nation tribe provided funding it received from the federal CARES Act for the cost.

Diné College is also trying something new. The reservation it serves is roughly 26,000 square miles, Roessel said, and students are driving an hour or more to campuses to use the internet from parking lots. In April, 86 percent of students did not have real access to the internet from their homes.

To solve this problem, Roessel would like to create microcampuses across the reservation and in remote areas, so students won't have to travel as far to get internet access. The college is finalizing agreements with three local areas on the reservation right now, he said. The microcampuses will have computers, broadband access and staff to ensure COVID-19 safety protocols are followed.

Once the Bureau of Indian Education opens up K-12 schools, the college hopes to use high school spaces for the same purpose, as well as to provide dual-credit classes. Roessel would also like to put a site at schools where students could come take classes from not only Diné, but also colleges like the University of Arizona.

Another idea is to add microcampuses in places like strip malls that also have Laundromats and grocery stores, he said. Parents could come to do errands, and their children could go get tutoring from Diné students who are in teacher education programs.

"We're looking at this as an opportunity to redefine how we approach education on a reservation," Roessel said. "It's one of the pluses that has come out of this."

Worried About Everything

Tribal college students tend to be less traditional. They're often older (the average age is about 31), or parents, or low income. Funding from the CARES Act has helped some colleges support students, for now.

Staff at Little Big Horn College have a stack of requests for financial support from students, Yarlott said. The college has been providing fuel vouchers for those who have to come to the college, as well as food vouchers for groceries. It's also cutting checks to vendors for rent and utilities if students need it, he said.

At Red Lake Nation College, more than 80 percent of the students have children of their own. Now they're homeschooling, on top of taking courses and working, King said. As a result, he's seeing many students experiencing the "COVID blues" from the combination of isolation and stress.

Resources on the reservation are stretched thin, so a student may have had to wait weeks to get a counseling appointment. The college used some grant funding to hire a tribal member to be a full-time psychologist, King said. The psychologist offers online counseling, as well as some face-to-face sessions if students prefer.

Emily Lockling, a 20-year-old student at Fond Du Lac College in Minnesota, said she's worried about everything: transferring to a university and paying for it, finding a job after college, continuing classes online.

The stress has bled into her studies.

"Usually when I'm a month into school, I'm still doing pretty good," Lockling said. "But I managed to fall behind on some of my classes, and I don't know how that happened. I just got so stressed that I stopped doing work for a week."

Fortunately, her professors are understanding, she said. But she worries about transferring to a four-year university next fall, and whether those professors will be the same.

She also wishes her college had virtual counseling. She hasn't received any notifications with that information.

Still, Lockling says she's lucky. She lives in a town next to the reservation with her parents, so she has internet and a laptop, though it doesn't run the map-making applications she needs for class very well. She had to buy a printer and a scanner to turn in assignments, and she bought a new computer for the fall because the battery gave out from so much use. But, over all, she's OK, she said.

The Navajo Nation has 35 percent unemployment, Roessel said, so Diné College students faced food insecurity when the pandemic hit.

The college expanded its emergency aid program to include buying hotspots and covering childcare and other costs, and it also gave a 50 percent tuition grant to all students who enrolled this fall.

"COVID-19 is not just a Wi-Fi issue -- it’s really about trying to meet the full needs of students," he said.

Effects of Neglect

Despite the solutions and successes so far, tribal colleges still have a long way to go with internet access.

Diné College invested $8 million of its CARES Act funding to upgrade its campus internet. That took it from having 400 MB/s for all six campuses to 2.5 Gb/s. But the average college of similar size to Diné has around 5 Gb/s, Roessel said.

"A lot of this initial investment just gets us to the starting line, while the rest of the colleges are at the 50-yard line," he said.

The federal legislation that should provide funding for building operations and maintenance at the college has never materialized, either, he said. The CARES Act was used to upgrade boilers and improve airflow because of this.

"Part of the challenges we have is not just because of COVID-19. It's because of the neglect of tribal colleges," Roessel said. "So when a pandemic happens, you really see where the cracks are."

Red Lake Nation College is also concerned about finances. It's underfunded, King said, but it serves students who need supports.

"Our average student comes in at about the ninth-grade level, very underprepared," he said.

The college receives about $8,800 per student from the Bureau of Indian Education, but little help from the state, King said. Federal operating funds don't cover everything they should, too.

Carrie Billy, president and CEO of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, said it's too soon to know how much trouble tribal colleges are in financially. It depends on how well tribal, county, state and federal governments can work together to build a solid technology infrastructure for the colleges.

So far, the CARES Act hasn't been enough. The 35 tribal colleges received $13.9 million, half of which went to students. It's because the formula used full-time-equivalent students, not student count, and most tribal college students attend part-time, Billy said.

The consortium has been advocating for E-rate eligibility for tribal colleges. The E-rate Program, also called the Schools and Libraries Program, provides discounts to schools and libraries so they can get affordable internet access and telecommunications services.

Internet providers often monopolize rural America, driving up prices. It's why tribal colleges have the slowest and most expensive internet of all institutions of higher education, Billy said. E-rate eligibility would help colleges build out internet access on reservations, solving many problems.

Crazy Bull, of the American Indian College Fund, doesn't think there will be closures in the near future, but she is concerned that tribal colleges won't be able to provide robust supports.

"I do consider this a federal trust responsibility," she said, adding that states also "haven’t historically stepped up and provided enough resources."

Still, college presidents are hopeful that this new wave of online learning will make their institutions stronger.

Diné College will continue upgrading its internet and technology, little by little, Roessel said.

"The Navajo Nation has been through much harder times than this," he said. "It’s not about survival. This is about exceeding our expectations."